Jews, Race, and Apocalypticism in Early Christianity

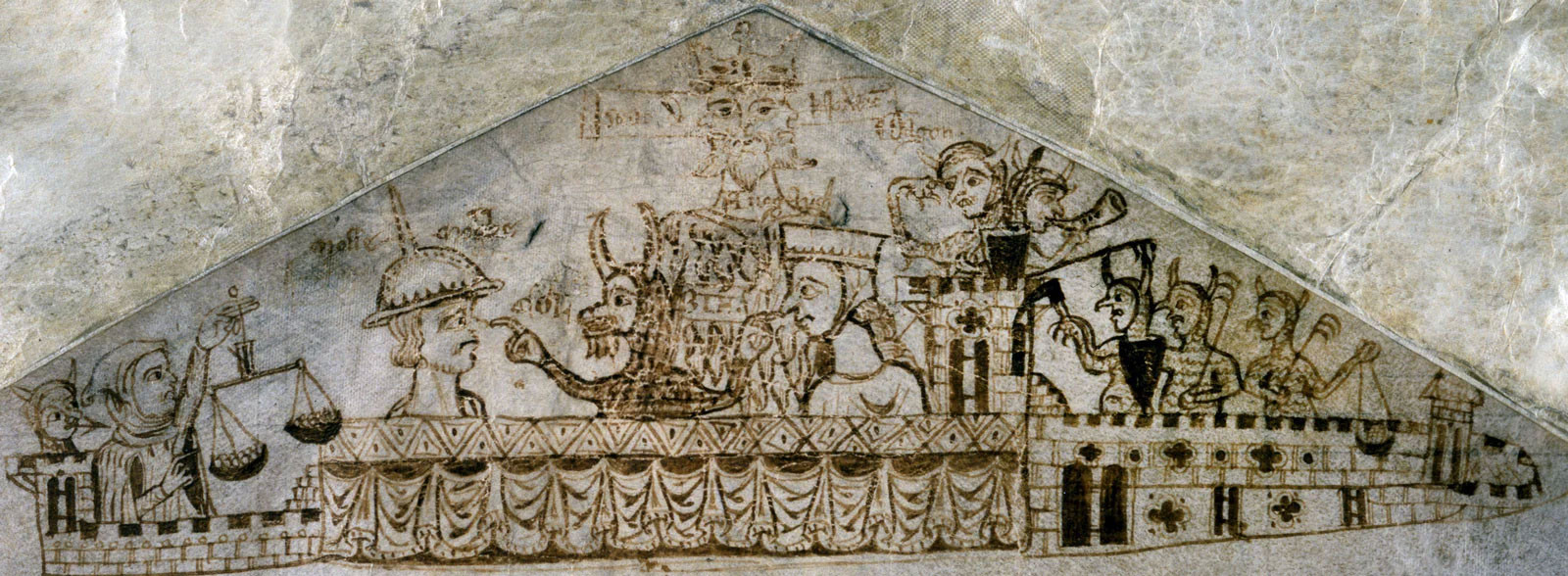

Exchequer Receipt Roll, 1233, The National Archives, London

My project addresses the difficult task of untangling the often intertwined analytic categories of race, ethnicity, and religion–particularly as these terms are applied to the history of Christian anti-Jewish ideologies and practices. The first part of my project analyzes the formulations of race and racism within standard historiographies of race to determine how historians have conventionally framed the history (and thus meaning) of race. Drawing from some of the models and approaches utilized by scholars working in the emerging field of premodern critical race studies, I make the case that scholarly uses of the terms race and ethnicity in the study of ancient societies remain inconsistent and problematic. Unreflective rejections of race as an analytic category, together with overgeneralized definitions of ethnicity, have left concealed important aspects of social identity formations that took place in the ancient Mediterranean. Following several significant works that have been published recently in Classics and early Christian studies (e.g. Buell 2005, Isaac 2006, McCoskey 2012, Derbew 2022), I make the case for the utility of the categories of race and racism in the study of early Christian identity formations.

The second part of my project provides working definitions of race and ethnicity that frames both concepts as robust analytic categories without collapsing the conceptual boundaries between the two. I then demonstrate the significance of naturalizing and somatizing discourses to processes of racial formation. I put forward a framework for reimagining early Christain identity formations by spotlighting the apocalyptic dimensions of early Christian thought. I demonstrate the ways in which apocalyptic notions of the natural world and the human body contribute to the conceptualization of the Jews as a distinct race. Given that racial formations are often dual-pronged endeavors, I also show how early Christian race-thinking vis-a-vis the Jews simultaneously shaped the ethnoracial concepts that early Christian writers used to identify themselves.

In the third part of my project, I focus on the post-Constantine era (i.e. fourth and fifth centuries) and discuss the increasingly fraught status of the Jews within the shifting socio-political structures that resulted in the Christianization of the empire. In the vein of works that study the racialization of the Jews in premodern Christian societies (e.g. Carter 2008, Kaplan 2018, Heng 2018), I demonstrate how changes in the legal system, as well as incidents of violence against the Jews, constitute examples of the earliest cases of Christain racialization of the Jews. The political isolation and ostracizing of the Jews in the fourth and fifth centuries serve as the background for the application of the race-thinking or racial logic that was already present in Christianity’s foundational myths.

The final part of my project provides a close reading of the reinventions of early Christian race-thinking within the writings of two key Christian authors living in the wakes of the Constantinian and Theodosian eras respectively: Eusebius and Augustine. In my reading of Eusebius’s apologetic treatises, I critique the problematic uses of ethnicity in earlier studies of the writings of Eusebius. Building on the model of racialization as a naturalizing and somatizing discourse, I highlight the methodical way in which Eusebius rewrites the history of the Jews with the goal of establishing them as a distinct race with its own historical lineage and concomitant set of innate traits. I then turn to Augustine’s writings on the Jews, focusing particularly on his portrayal of the Jews as “a carnal race” in the City of God. While much attention has been paid to Augustine’s “witness doctrine” and its mitigation of Christian violence toward the Jews, relatively little work has been done on how Augustine’s writings help extend the racial logics of earlier Christian texts. I aim to fill this gap by demonstrating how, despite the important nuances in his thinking, Augustine’s formulation of the Jewish identity extends a racialized paradigm that subsequent Christians would utilize to identify both themselves and the Jews.