Muslim Plague Martyrs

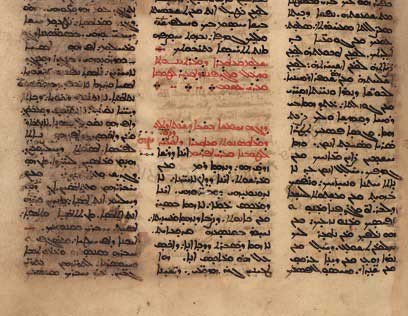

Codex Vaticanus Syriacus 117

My research on this collaborative project is focused on what I call the "hard problem" of interreligious and interconfessional history writing. The hard problem is this: how can we detect imprints or influences from other faiths within genres of religious literature that are reluctant to admit to this influence? Jewish, Christian, or Muslim chronicles are filled with information about interfaith relations, and certain genres of apologetic or polemic literature within the Abrahamic traditions tell us a great deal about how these sibling faiths beat the bounds of their identities against one another's example. But as a general rule, the more dogmatic and prescriptive forms of religious literature within each of the three traditions are deeply reluctant to admit to the pressure exerted by their siblings. Is it possible to read against the grain of these dogmatic genres, and discover the imprints of the other faiths in places where they might not immediately be apparent? I believe that it is possible, albeit difficult, and my time on the project will be devoted to proving my point through a detailed case study.ext

My case study is an analysis of the divergent theological meanings of plague in the late antique Christian and early Islamic traditions. All the faith groups of the eastern Mediterranean were forced to confront the horror of endemic Yersinia Pestis—bubonic plague—and many other forms of epidemic disease. This was a theological problem as much as it was a public health problem, because plague could be interpreted as an expression of divine favor or disfavor on a specific community. One specific phenomenon within the Muslim tradition of dogma is especially telling: the birth of the Muslim plague martyr.

Long before the advent of Islam, the late antique Christian tradition had come to identify outbreaks of plague as a form of divine discipline: God sent plague as a corrective on His chosen people when they had fallen into collective sin. I believe that the distinctive Muslim tradition of plague martyrdom was directly shaped by this counterexample. Through they rarely acknowledge the pressure of Christian influence directly, Muslim traditions on the plague are at pains to emphasize that plague does not represent a divine punishment, but a divine mercy. In fact, for the Muslim who bears up patiently and respects quarantine protocols, death by the plague grants the same rewards of martyrdom as death while "fighting in God's path." Some traditions go even further, specifying that plague is a punishment for non-Muslims, but a martyrdom for faithful Muslims.

I believe that this peculiar dogma has been "co-produced" by Christians and Muslims. Faced with a preexisting Abrahamic community that understood plague as a divine punishment, the young Muslim tradition was compelled to sketch out an alternative meaning for its own community—conceding that plague was a punishment on non-Muslims, but nevertheless insisting that it had a special theological meaning for the new religious community. The result is a fascinating keyhole on how future research might address the "hard problem" of interfaith history.