Porous Communal Boundaries and the Jewish-Muslim Co-Production of Legal Norms in Fāṭimid Egypt (11th–12th C.)

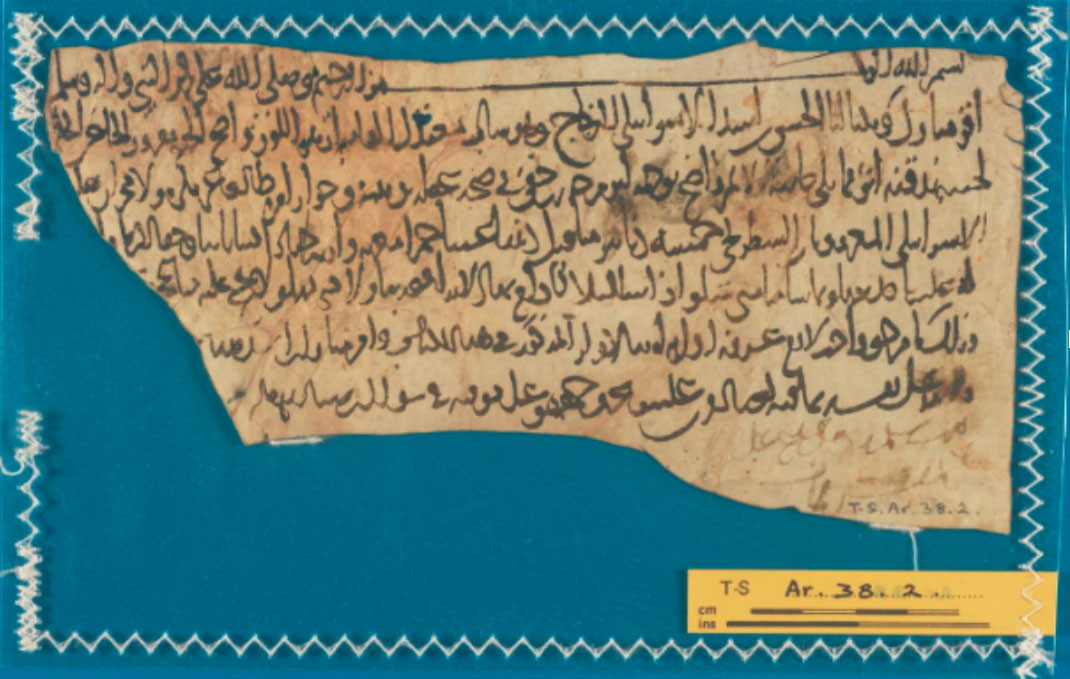

Debt Acknowledgement (Iqrār) between Abū al-Shaṭranjī and Abū al-Ḥasan ibn Asad Mubārak Date: Shawwal 400 AH/ May-June 1010 CE, Source: T-S Ar. 38.2 Cambridge University, Taylor-Schechter Collection

During her postdoctoral fellowship, Islam will be working on her second project, Porous Communal Boundaries and the Jewish-Muslim Co-Production of Legal Norms in Fāṭimid Egypt (11th–12th centuries CE): The Case of Islamic and Jewish Iqrārs in the Cairo Geniza. In Fāṭimid Egypt, despite the halakhic prohibition against bringing Jewish legal cases before Gentile judiciaries and warnings of excommunication on this basis, Jews regularly adjudicated a variety of cases through Islamic courts. Likewise, despite pervading beliefs that Islamic legal norms emerged entirely from within the Islamic legal tradition, documentary evidence demonstrates that Muslim jurists borrowed from other Near Eastern legal traditions in establishing Fāṭimid Islamic institutional legal norms and documentary practices.

Using letters, court records, chancery documents, and previously unresearched debt acknowledgements (known as iqrārs in the Jewish and Islamic legal traditions) in Arabic, Judeo-Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic from the Cairo Geniza, she examines: 1) why and how Jews and Muslims in the Fāṭimid period traversed porous communal boundaries in addressing legal issues; and 2) how Jewish and Islamic legal norms influenced each other, especially as medieval legal culture shifted from prioritizing oral testimony to relying on written evidence in judicial settings.

Prior studies using Geniza source material have largely focused on the narrative anecdotal evidence that single or small collections of documents could provide. Challenges of access and limitations in technology inhibited studies beyond this scope. With the digitization of the global Geniza corpus within the past five years, we can now study large corpora of manuscripts from a single genre (or representative samples). When we study the entire corpus of a documentary genre instead of one document at a time, previously unnoticed patterns emerge that elucidate the genre’s formulary, typologies, and material norms. This new information, when combined with social historical analysis, sharpens our knowledge of the document’s institutional milieu and the social actors who produced it, far beyond what an individual document can tell us.

Her project adopts this approach for studying the iqrār genre. The iqrār was a notarized and witnessed legal document drawn up between a creditor and debtor acknowledging that a debt was owed (similar to what in U.S. common law is called a security agreement). In the Fāṭimid period, iqrārs were drawn up to avoid complex litigation in courts and existed in both Islamic and Jewish legal traditions. The ubiquitous usage of iqrārs between neighbors, family members, and tradesmen for all sorts of material exchange, not just monetary, makes studying its corpus essential to understanding how medieval legal systems functioned on the ground. In this project, she investigates the iqrār corpus in addition to related loan documents and testimony agreements, examining material aspects of the document, formulary, language, and format as well as narrative details. In examining patterns over a large corpus, she will trace when and how Jewish and Muslim litigants, whether intentionally or not, engaged in implicit and structural co-production, whereby each legal system absorbed aspects of the other in attempts to address specific societal or legal concerns.