Maureen Attali , 2024

A Co-Produced Tradition about the Messiah and His Mother in Late Antique Rabbinic Literature

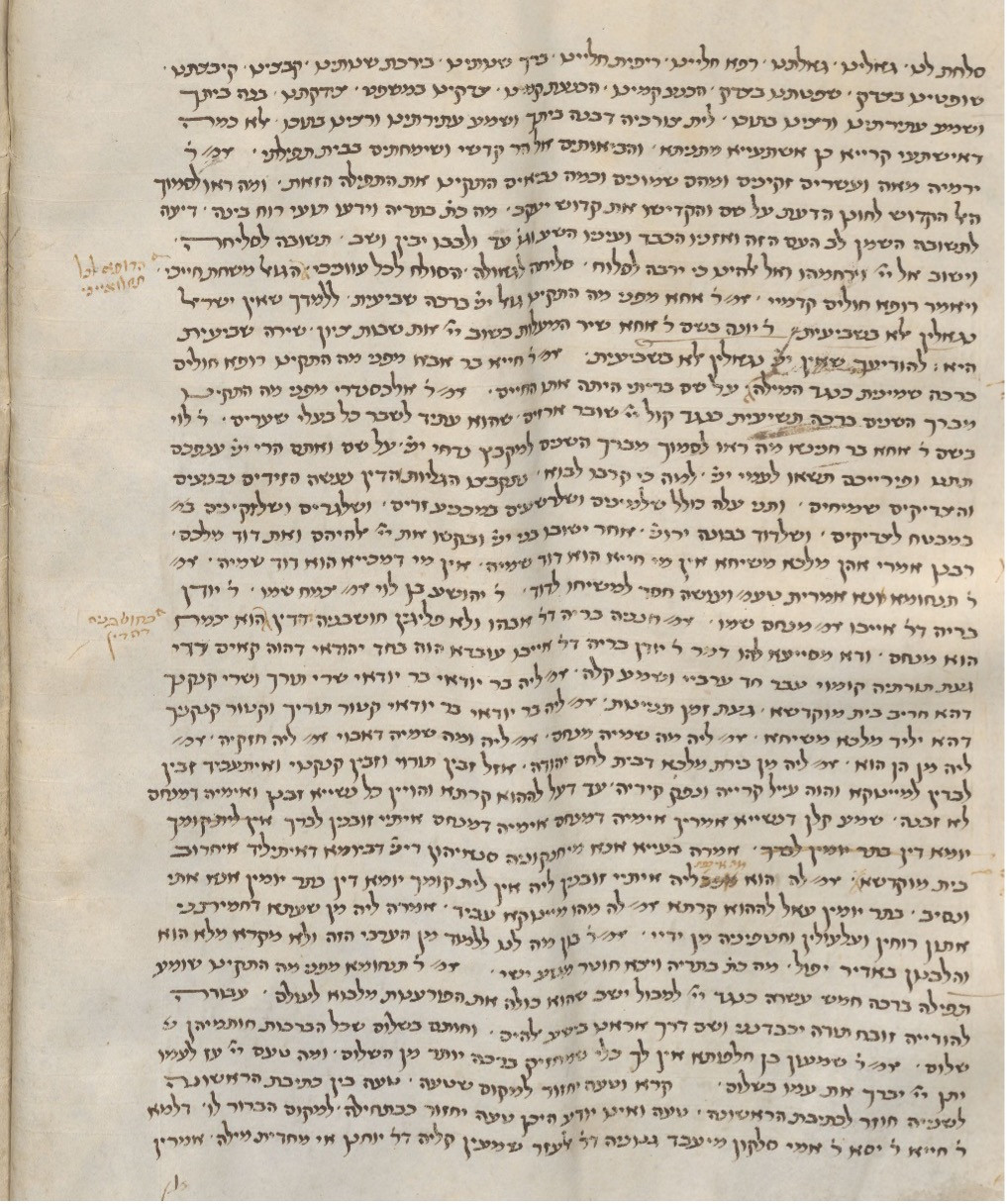

Tractate Berakhot 2:4 in the Leiden manuscript of the Palestinian Talmud (Or. 4720), copied in Italy in 1289 by Jehiel ben Jekuthiel ben Benjamin Ha-Rofe. Leiden University Libraries http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:937041

The Hebrew word mashia’h, meaning “anointed”, originally referred to people whose special relationship with God was sanctioned by a ritual act involving the rubbing of oil. In the Hebrew Bible, it is applied to priests, prophets, and kings, some also called “son of God” and/or “son of man”. Christian tradition has interpreted all these as references to Jesus, called “Christ”, the Greek translation of mashia’h. The analysis of a 4th-century rabbinic story about a historical Messiah born on earth at the end of the 1st century CE allows us to see how the characteristics attributed to the Messiah in late antiquity were shared and co-produced among Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

A 4th-century Rabbinic Story about a Historical Jewish Messiah

We have two versions of a fourth-century story. Both begin with an Arab passer-by and a Jewish ploughman. The Arab explains that the twofold lowing – or bellowing – of the ploughman’s ox represents two quasi-simultaneous events: the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem, closely followed by the birth of the messiah, whose name is Menachem ben Hezekiah, in Bethlehem, and, in one variant, in the “king’s palace”. The Jew then becomes a peddler of swaddling clothes. He travels all around Judaea and ends up in Bethlehem, where he meets Menachem’s mother. According to one version (found in the Talmud), the woman expresses her wish to strangle her son because he was born on the day the temple was destroyed. In the other (preserved in a biblical commentary), she fears for him because of the day of his birth. In both cases, the peddler announces that Menachem will be instrumental in the restoration of the temple; since his mother is too poor to afford buying baby clothes, he gives them to her. Later, the peddler comes back to Bethlehem and asks Menachem’s mother about her son. He then learns that he was taken away in a storm shortly after his last visit.

The two different versions of this story are both attributed to rabbi Aivu, who, according to rabbinic tradition, lived in Palestine in the 4th century. The earliest, written in Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, is found in the Palestinian Talmud (Berakhot 2.4), compiled in the late 4th century; a variant was included in a Palestinian biblical commentary in Hebrew (Midrash Rabbah on Lamentations 1.16 §51) written around 500. The story is fascinating for two reasons. First, it is the only Talmudic passage that provides a precise historical context for the arrival of the messiah. Second, in addition to shared references to his Davidic lineage (Isaiah 11:1) and his birth in Bethlehem (Micah 5:2), there are many parallels between Menachem’s story and the Gospels’ accounts of Jesus’s birth (Matthew 2:1–12; Luke 2:8–21). Foreigner(s) – the Arab passer-by versus the three Persian mages – are the first to know of the birth of the messiah, on the basis of natural phenomena – the lowing ox or the star – which they interpret as signs. It is announced to farmers, either ploughman or shepherds. The newborn messiah, who is from a poor family, is found after much wandering and is given gifts (swaddling clothes or gold, incense, and myrrh), but finds himself in grave danger either from his own mother or from King Herod.

How do we account for such similarities? The multi-layered story allows for a wealth of interpretations, sometimes contradictory.

A Jewish Dialogue with Christian Representations of the Messiah?

Because prior to this 4th-century Talmudic passage the idea that the Messiah would appear as a baby born of a woman was not documented in any Jewish source, Menachem’s biography can be read as rabbinic response to Christian representations of the Messiah, a conscious engagement with stories about Jesus. However, such interpretations diverge widely in the meaning(s) and function(s) they ascribe to the rabbinic story.

Martha Himmelfarb has interpreted it as a response to the aspirations of a Jewish population seduced by the characteristics of the Christian Messiah, and especially by the figure of Mary, which had become ubiquitous in the late Roman urban landscape. The two versions of the story, which differ in the mother’s attitude towards her son, show that the Palestinian rabbis tried two diametrically opposed strategies of dealing with Jewish interest in the mother of the messiah. The Talmudic account of the mother threatening her son should be understood as a criticism of the idyllic portrayal of Jesus’s family, expressing a rejection of Jews adopting of these Christian traditions. On the contrary, the biblical commentary, in which the mother is nothing but loving and protective, suggests that some rabbis accepted the possibility of a Jewish focus on the mother of the messiah, and thus entertained the interest of their fellow Jews in this figure.

Alternatively, and while explicitly building on Himmelfarb’s study, Peter Schaefer considered the irenic version to be a distortion of the original rabbinic story, which he interpreted as a parody of the Christian biography of Jesus, whose purpose was to deny his messiahship. The story, which greatly diminishes the scale of the circumstances of Jesus’s birth, emphasizes that the Jesus whose story is told in the Gospels cannot be the salvific messiah, since he disappeared without establishing the kingdom of God. The mother knows that the birth of her son is linked to the tragic destruction of the Jerusalem temple. This made her want to forestall him, but she did not do so, thus refuting the Christian claim that the Jews had killed the Messiah.

The story could also be a polemical take on the meaning of the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, which Christians from the 2nd century onwards interpreted as divine punishment for the sinful Jews who refused to recognize Jesus as the Messiah.

The Co-Production of Biblical and Graeco-Roman Literary Traditions

Many features of these messianic biographies were not specific to Jewish and Christian literature. Their structure has close parallels in contemporary Greek novels and in late antique biographies of “holy men” from various religious contexts. Such works often featured learned foreigners, prophecies, humble characters, protagonists born on fateful days into poor families, as well as sudden disappearances in extreme meteorological conditions.

Menachem’s story combines this literary framework with Graeco-Roman ethnographic stereotypes – the Arabs as interpreters of animal behaviour – and elements relating to the messiah(s) in the Hebrew Bible. Indeed, a Messiah often appears in biblical visions of Israel’s restoration, especially in the Books of Jeremiah and Isaiah. The peddler’s suggestion that Menachem will return echoes the biblical story of the prophet Elijah, who did not die but “went up by a whirlwind into heaven” (2 Kings 2:11) and will return before “the great and awesome day of the Lord” (Malachi 3:23 = 4:5).

Although it was not ultimately included in the canon of the Hebrew Bible, the association of the death of a woman’s son with the destruction of Jerusalem and the announcement of its restoration was not unknown in Jewish literature before the 4th century. In a Jewish apocalyptic text written in the late-1st century CE but only preserved in Christian Latin translations, the biblical scribe and priest Ezra has a vision of a mourning woman; she tells him of her son who died on his wedding day, before she transforms into a beautiful city. The angel Uriel then explains to Ezra that the death of the woman’s son is the destruction of Jerusalem, and that the city is the restored Zion (4 Esdras 9:38–10:59).

Both Menachem’s and Jesus’s biographies could thus have developed from a shared messianic narrative based on biblical and Graeco-Roman literary features that circulated in Judaea in the 1st century CE. An endangered Messiah, announced by a sign, would be carried by a woman, and be taken by God before returning to establish his kingdom on earth. This narrative canvas is sketched out in a vision from the Book of Revelation (12:1–5), replete with biblical references:

And a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars. She was pregnant and was crying out in birth pains and the agony of giving birth. And another sign appeared in heaven: behold, a great red dragon with seven heads and ten horns, and on his heads seven diadems. His tail swept down a third of the stars of heaven and cast them to the earth. And the dragon stood before the woman who was about to give birth, so that when she bore her child he might devour it. She gave birth to a male child, lone who is to rule all the nations with a rod of iron, but her child was caught up to God and to his throne.

The Debate about Historical Messiahs

Although the general history of rival claims to the messianic is well-known, looking at the details of our rabbinic story highlights how dynamic the co-production was, and how creatively the various communities reacted to their understanding of rival claims. Indeed, while many late antique Jews and Christians believed in an upcoming messianic saviour, his characteristics were debated. The Christian Messiah was a historical one: he first appeared in Judaea, where he was born under the reign of King Herod, sometime between 5 BCE and 1 CE according to the Gregorian calendar. Jesus of Nazareth interacted with well-known historical figures, such as the Roman procurator Pontius Pilatus.

The identification of Jesus as the Messiah is the product of Jewish messianism, which developed strongly from the Hellenistic period onwards. Many apocalyptic writings were produced in Judaea from 170 BCE, in the wake of the war against the Seleucid rulers. The Jewish community that produced the Dead Sea scrolls was waiting on the arrival of providential messiahs (1 QS [= Community Rule] 9.11). Several Jews who rebelled against Roman rule were seemingly interpreted as messianic candidates. The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, writing in the late 1st century CE, lists several of them, including one named Menachem ben Judah ben Hezekiah; he led a revolt against the Romans and their Herodian allies in 66 CE (Jewish War 2:433–448). This Menachem was soon killed, but his actions ultimately led to the destruction of Jerusalem temple four years later. A 4th-century rabbinic passage (Palestinian Talmud, Taanit 4.5) states that rabbi Akiva hailed his contemporary Simon ben Kosiba, the leader of a Judean revolt against Rome between 131 and 135/6, as “King Messiah” (melekh mashia’h) until he was killed by Roman soldiers.

While the Talmud only records a handful of messianic discussions, the longest one (Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 98b-99a) deals with the duration of the anticipated messianic era, the events leading up to the arrival of “David’s son”, as well as with possible names for him. Among them is Menachem ben Hezekiah, a suggestion is explicitly based on a biblical verse (Lamentations 1:16) featuring the Hebrew word menachem, which literally means “comforter”. Menachem’s identification as a descendant of someone named Hezekiah could allude to the similarly named leader of the 1st-century CE revolt, as well as to the biblical King Hezekiah, whom rabbinic exegesis suggests God intended to be the salvific messiah (Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 94a). For indeed, not all late antique Jews thought that a messiah would come for Israel; 4th-century rabbi Hillel stated he had already come during the reign of Hezekiah and would not return.

The function ascribed to Menachem’s story by late antique rabbis has been debated. Based on rabbinic opinions about the attitude Jews should adopt after the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, Jonah Fraenkel interpreted this messianic narrative as a rabbinic cautionary tale, intended to dissuade Jews from isolating themselves in perpetual mourning. The ploughman who left everything in search of an illusory Messiah and the mother who found herself without her child are counter-models not to be emulated. On the contrary, Jews must carry out their daily tasks.

Regardless, whether the rabbinic story contained intended references to Jesus, and whatever its purpose, its existence attests to the fact that, from the 4th century at the latest, Jews and Christians were engaged in discussions about a (potential) historical messiah and his biography, a conversation in which they were later joined by Muslims.

Messianic Features in Muslim traditions: Jesus and a Comforting Muhammad

We tend to think of Islam as not messianic, since the Qur’an does not announce the return of Muhammad. However, many Muslim traditions feature Jesus, whom the Qur’an mentions was called “messiah”, in Arabic masiḥ (9:30–31, surah al-Tawbah, “The Repentance”) and who “shall be a sign of the hour” (43:61, surah al-Zukhruf, “The Embellishment”). According to early Muslim apocalyptic texts (al-Samarqandi, Tanbih, 209; Ibn al-Munadi, Malahim, 209–11; al-Dani, al-Sunan al-wārida fī al-fitan III, 1103-1104; Al-Sulami, Iqd al-durar fi akhbar al-muntazar 267-68), Jesus will return at the end of times to lead the Muslims to victory against the army of the “Deceiver” (Dajjal) before establishing his rule on earth. It is only gradually that he was relegated to a subordinate role, replaced by a descendant of Muhammad’s family.

Additionally, features of late antique messianic biographies were ascribed to Muhammad himself. In the early 9th-century, the Muslim writer Ibn Hisham composed a Life of the Prophet, a revision of an 8th-century work by Ibn Ishaq. Although he never defines Muhammad as a messiah, he includes elements reminiscent of Jewish and Christian messianic biographies: his pregnant mother receives a sign that he will have a great future; he is born during the year when Abraha is said to have wanted to destroy the temple of Mecca; an unnamed Jew announces his birth; his life is threatened by the fact that no one will nurse him; Abyssinian Christians recognize that he will have a great future. When Ibn Hisham recounts that the Christian monk Bahira recognised Muhammad as a prophet because he found his description in his books, he quotes this description, including the following verse:

When the Comforter has come, whom I will send to you from the Father the Spirit of truth, who proceeds from the Father, he will testify about me (John 15:26).

This Arabic quotation from the Gospel of John is translated from the Palestinian Syriac Lectionary, which renders the Greek word paraclētos (“helper”), used to describe Jesus, by the Syriac mnahmana, which, like the Hebrew menachem, means “comforter”. The author then explains that “the Munhamanna in Syriac is Muḥammad; in Greek, he is the Paraclete”, apparently playing on the assonance between the Syriac mnahmana and the Arabic muhammad, “praiseworthy”. These echoes of Jesus and Menachem in a Muslim description of Muhammad are but one strand of a late antique co-produced messianic biography which combined features of biblical and Graeco-Roman literature and circulated in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic circles.

Further reading:

Brown, Peter, “The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity,” The Journal of Roman Studies 61 (1971): 80–101 https://doi.org/10.2307/300008

Cook, David, Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic (Princeton, 2002).

Fraenkel, Jonah, עיונים בעולמו הרוחני של סיפור האגדה (Tel Aviv, 1981).

Hasan-Rokem, Galit, Web of Life: Folklore and Midrash in Rabbinic Literature (Stanford, 2000).

Himmelfarb, Martha, “The Mother of the Messiah in the Talmud Yerushalmi and Sefer Zerubabbel,” in Peter Schäfer (ed), The Talmud Yerushalmi and Graeco-Roman culture, v Vol. 3 (Tübingen, 2002), 369–389.

Knohl, Israel, The Messiah before Jesus: The Suffering Servant of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Berkeley, 2000).

Lévi, Israël, “Le ravissement du Messie à sa naissance,” Revue des études juives 74.148 (1922), 113–126 https://doi.org/10.3406/rjuiv.1922.5360

Schaefer, Peter, The Jewish Jesus: How Judaism and Christianity Shaped Each Other (Princeton, 2012).

Shoemaker, Stephen J., The Apocalypse of Empire: Imperial Eschatology in Late Antiquity and Early Islam (Philadelphia, 2018).