Anthony Ellis , 2024

Genealogizing Deviance: George of Trebizond on the Islamo-Platonic Conspiracy of Gemistos Pletho

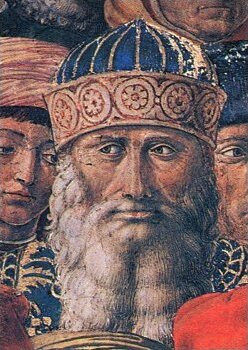

Figure 1: Detail from East Wall of the Chapel of the Magi, Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence, by Benozzo Gozzoli, ca. 1459 (Public Domain; Wikimedia Commons)

Gemistos Pletho and the Birth of the Controversy

Soon after his death in 1454, Georgios Gemistos – better known by his philosophical nickname “Pletho” – became the subject of bitter polemic. In the Latin-speaking world, the first blow was struck by George of Trebizond (1396–1472), who described Gemistos in the following terms:

Another Mohammed has now been born and raised to us and, unless we take precautions, he will prove more deadly than Mohammed, just as Mohammed was more pernicious than Plato.

In the Peloponnese there was a certain man who in eloquence, learning, and piety was a student of Plato. His name in the vernacular was Gemistus, but he gave himself the cognomen Pletho. [...] He is well known to have been such a Platonist that he professed the truth to be nothing other than what Plato believed concerning the gods, the soul, and sacrifices to the gods or demons. [...]

I myself heard him in Florence [...] asserting that in a few more years the whole world would take up one and the same religion [...]. And when I asked him whether it would be that of Christ or Mohammed, he replied that it would be neither, but rather one not much different from paganism. Deeply disturbed by these words, from that point on I have always hated the man and feared him as a venomous viper. [...].

Word has it that the book he composed concerning these matters was confiscated and concealed by Demetrius, the prince of the Peloponnese, lest it be out in the public to be read and so inflict harm upon many. So let it be consigned to the fire [...].

Comparatio Philosophorum Platonis et Aristotelis 3.20.1-8

(trans. John Monfasani, adapted)

Trapezuntios was not the only contemporary to view Gemistos with horrified fascination. The most shocking revelations came after Gemistos’s death, when a book he had written – called the Laws – came into the hands of the Byzantine imperial family. This work described a utopian state with philosophical foundations in Neoplatonism. It broke radically with the Orthodox Christian society in which Gemistos lived by prescribing a religious cult based on the ancient gods of pagan Greece, with a complex liturgical system of prayers to Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, and the other pagan deities – gods whose cults had been banned in the Roman empire for almost a thousand years.

Trapezuntius had only heard rumours of the book and its contents. Others had seen it in full. The text eventually came into the hands of Gemistos’s old rival, George Scholarios, who served several times as Patriarch of the Orthodox Church under the new Ottoman state. Scholarios declared Gemistos a polytheist and apostate and he burnt the majority of the work, preserving only enough to prove its heretical nature. He ordered everybody who had a copy to destroy it and threatened anyone who refused with excommunication. Like Trapezuntius, Scholarios sketched a polemical biography of Gemistos, but he traced Gemistos’s heretical views back not to Mohammed, but rather to the teaching of an apostate Jew called Elissaios, with whom – he claims – Pletho had studied as a youth, when he lived at the Ottoman court.

Despite the shocking evidence of Gemistos’s theological deviance, and these very public condemnations, admiration for Gemistos died hard. One of his former pupils, Bessarion, was a powerful Roman cardinal who would twice come close to being elected pope. In a letter of condolence to Gemistos’s sons, written in the mid 1450s, Bessarion describes Gemistos – their “shared father and guide” – as the wisest man to have lived since Plato. If one were to accept Pythagorean and Platonic beliefs in reincarnation, Bessarion wrote, one would think that Plato’s soul had returned in Gemistos’s body. Gemistos ultimately became a positive figure in the mythology of Renaissance Platonism – “a second Plato”, in the words of Marsilio Ficino, who claimed that his lectures in Florence in 1439 had inspired Cosimo de’ Medici to found a Platonic academy. The legend has led some to think that Pletho might be the inspiration for a bearded figure in the Procession of the Magi in the Medici Palazzo in Florence, commissioned by Cosimo (see Figure 1). Some rulers made even more public displays of respect. Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, prince of Rimini, on campaign in the Peloponnese in 1464, exhumed Gemistos’s remains and brought them back to Rimini, where he reinterred them in his newly built Tempio Malatestiano. The inscription, which can be read today on a marble sarcophagus along the external flak of the Church [Fig. 2], declares Gemistos “prince of the philosophers of his time”. George Trapezuntius claims to have confronted Sigismondo to warn him against polluting a Christian church with demons like “the Apollo who lives in the body of Gemistos”. But, although Sigismondo fell sick and died just a few years later, Trapezuntius’s view of Gemistos failed to gain traction. Despite what seemed to him overwhelming evidence that Gemistos was an enemy of Christianity, few wanted to hear the story he told. Against this background, it’s worth taking a closer look at the remarkable cosmic drama which Trapezuntius narrated in his early attempts to galvanize public opinion against Gemistos.

Figure 2, The Tomb of Gemistos Pletho: External wall of the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini (Public Domain; Wikimedia Commons)

George Trapezuntius and the Devil’s Islamo-Platonic Conspiracy

Trapezuntius’s Comparison of the Philosophers Plato and Aristotle, written in 1457, purported to be a dutiful attempt to set right the gross philosophical and technical mistakes of a Latin translation of Aristotle’s Problems which had been made by Theodore Gazes, another Greek émigré in Italy. But the Comparison was also written to settle a grudge. Originally, Trapezuntius had been commissioned by Pope Nicholas V to translate Aristotle’s Problems, but he lost the commission in early 1452 after he came to blows with the papal secretary, Poggio Bracciolini, and fled Rome. The commission then went to Theodore Gazes, partly through the offices of Gazes’s patron, Bessarion. In the Comparison, Trapezuntius set out to destroy the reputation of both men. He chose a bold strategy: to present some questionable liberties which Gazes had taken with the text of Aristotle as part of a Platonist conspiracy to defame Aristotle and, thereby, to destroy Christianity. Gazes’s mistranslations were alleged to be a first step in the plot to undermine Aristotelianism – understood as the philosophical foundation of Christianity – and replace it with Platonism, alleged to be inimical to Christianity. Trapezuntius left the conspirators anonymous but, true to the tone of contemporary scholarly polemic, he dubbed them the Cagulei – a thinly disguised reference to Theodore “Gazes” which translates roughly as “the Shites” (echoing Italian cagà).

One of Trapezuntius’s major points of attack was the theological deviance of Bessarion’s former teacher, Gemistos Pletho, especially his apparent abandonment of Christianity for paganism and Platonic philosophy. But Trapezuntius used this fact in an unexpected way: he built it into a new master-narrative, loosely drawn from Christian heresiology, which claimed that Platonism was the Devil’s favourite weapon in his eternal onslaught on Christianity. Trapezuntius asserted that the ancient philosopher Plato was the origin of “every heretical perversity” that had beset the Church, from the doctrines of Arius and Eunomius, to the schism between Eastern and Western churches, to contemporary controversies within the Orthodox Church. In the closing sections of the Comparison, Trapezuntius deployed his master stroke by simplifying the history of religious error to four diabolical leaders – four “Platos” – and presenting Platonism and Islam as part of a unified assault on Catholicism. After showing how Plato’s doctrines precipitated the downfall of the ancient Greeks, he offered successive chapters on Epicurus, Mohammed, and finally Gemistos, each of whom were identified as imitators and students of the original evil mastermind, Plato. The story drew on the traditional motif of heretical succession, whereby heretics were linked with one another in a ghoulish imitation of apostolic succession.

Trapezuntius’s discussion of Islam was in particularly close dialogue with the treatment of Mohammed in Christian heresiology, even as it changed the story’s details. In the Middle Ages, one of the most popular Christian accounts of the genesis of Islam starred a heretical monk (often named Sergius Bahira) who, along with a Jew, met a crude swineherd (Mohammed) in the Arabian desert, taught him of the Bible, and indoctrinated him with heretical ideas. Armed with these, the story went, Mohammed conquered the world and set about destroying Christianity (naturally with the help of Satan). The legend appears as early as the 7th century, when John of Damascus listed Islam as the hundredth (Christian) heresy. Earlier heresiologists typically tailored the identity of Sergius Bahira’s heresy to fit their own social and theological needs: in some versions he was an Arian, in others a Jacobite or a Nestorian. Trapezuntius participates in this tradition of creative adaption by making Mohammed’s Christian teacher a “Platonic” heretic from Alexandria – the home of Christian Platonism – so that the seed planted by Plato flourished in Mohammed, who ultimately surpassed his master. For Trapezuntius, Mohammed was “a Platonist in spirit, a Jew in words, and an enemy of Christianity”. In a striking though probably coincidental echo of Bessarion’s eulogy of Gemistos, Trapezuntius writes that even if one imagined Plato’s soul reincarnated in Mohammed’s body, their doctrines could not have agreed more closely.

The Comparison’s culminating chapter then presents Gemistos as a “new Mohammed”, as far superior to Mohammed as Mohammed was to Plato. Trapezuntius thus unmasked all three men as partisans of the same diabolical movement, and the Platonization of Christianity as the intellectual counterpart to the military onslaught of Islamic empires on Christendom. George, of course, could reckon with a readership still traumatized by the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, just four years earlier. The students and admirers of Gemistos were thereby exposed as a fifth column at work within the Roman Church, and their hostility to Trapezuntius an inevitable byproduct of their wicked plot.

Given Trapezuntius’s debt to Christian heresiology, it is striking that he never calls Gemistos a “heretic” at any point in the long chapter on him. His favourite term for Gemistos’s beliefs is “paganism” (gentilitas). But Trapezuntius seems to have intentionally avoided clean distinctions between concepts like “heretic”, “pagan”, “philosopher”, and “Muslim”. In this, he followed in the footsteps of many earlier heresiologists, like Epiphanius of Salamis and John of Damascus, who swept various forms of Judaism, pagan philosophy, and all non-Christian religions into the same heresiological master-narrative, in which true Christianity was the continuation of a primal orthodoxy, and all other beliefs – paganism, Judaism, Islam, philosophical movements, and Christian heresies – were diabolical deviations from that ancient path.

Trapezuntius also drew on the Christian heresiological tradition in subtler ways. He describes Gemistos as a “venomous viper” (venenosa vipera), he compares him to a “beast” (bestia), and he likens his ideology to a poisonous tree whose roots must be pulled up before its noxious shadows cover the world. Elsewhere, Platonism is presented as the seed from which Islam has sprouted. These metaphors were standard fare in the heresiological tradition, which presented heresy as a poisonous creature, a wild or diseased animal, or a plant which had to be exterminated before its doctrine – venom, sickness, spore, or seed – could corrupt healthy Christians. Likewise, each of these four “Platos” are presented as Satan’s lackies. True to form, Trapezuntius gave himself a starring role in this cosmic drama as a visionary prophet persecuted by the forces of Satan, a lone voice brave enough to oppose this latest Platonic conspiracy. He was particularly vocal about his fear that Gemistos’s Platonism, if not stamped out quickly, might gain the support of “powerful people” and grow to unstoppable proportions, in a nightmarish repetition of the history of Islam, whose early tolerance by the emperors of the Byzantine world had ultimately led to the downfall of the whole empire.

George Trapezuntius was not a happy man. In spite of his obvious intellectual abilities, his life was punctuated by social and professional catastrophes. His most spectacular political faux pas seems to have been driven by the conviction that he was divinely chosen to save Christianity. After the failure of his attempts to convert Mehmed II to Christianity by letter, he resolved to visit Constantinople to seek a personal audience with the Sultan. He did not succeed but, after his return to Italy in mid 1466, Trapezuntius rededicated several of his philosophical writings to Mehmed and hailed him as Roman Caesar and ruler of Europe. The gesture achieved nothing more than Trapezuntius’s incarceration at the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome on a charge of treason, with Bessarion as his chief accuser. But Trapezuntius’s prophetic self-conception illuminates some of his claims about Gemistos. His report of Gemistos’s prediction of an imminent mass conversion to Platonic paganism smacks of Christian apocalypticism and is likely to be co-produced. Trapezuntius seems to be projecting his own habits of thought onto the dead philosopher, to make him better fit the part he had been allotted in this millenarian drama.

The Origins of Neopagan Polytheism: Jewish or Islamic?

The very different intellectual genealogy constructed for Gemistos by his other great detractor – George Scholarios – makes for an illuminating contrast. Scholarios makes much of Gemistos’s discipleship with an apostate Jew (Elissaeus / Elisha) in the Ottoman court. The motif of a Christian led into theological error by a Jew is a classic of the heresiological tradition. “Judaizing” was a standard slur in inner-Christian polemic, and some scholars suspect that Scholarios’s claims are fabrications woven to play on generic stereotypes. Trapezuntius, by contrast, makes no mention of Gemistos’s Jewish teacher and Jews generally play little role in his Comparison. Writing in Christian Italy, Trapezuntius instead attacked Gemistos and his Platonism by associating them with the diabolical forces of Islam. This was a difficult path for Scholarios, who, by this point, had become a prominent figure in the Ottoman Muslim administration.

In reality, of course, neither of the other revealed monotheisms – Judaism and Islam – seemed a likely source for Gemistos’s rationalizing Platonism. Gemistos’s own philosophy rejected the need for revelation: he made no recourse to Jewish, Christian, or Islamic scriptures and he completely ignored their culture heroes (Moses, the Hebrew prophets, Jesus, Mohammed, etc.) in favour of a different line of sages which ran from the ancient Persian Zoroaster through to the Greek philosophers. Even more puzzling is the claim that Gemistos’s polytheism might somehow be explained by contact with Jewish or Islamic thinkers. Both Judaism and Islam could make a far more plausible case to be “monotheist” than Catholic or Orthodox Christianity, the nature of whose “monotheism” is notoriously mysterious, in view of its three gods. The philosophical arguments used to reconcile Christian theology with the inherited claim to a monotheistic faith were, of course, largely plundered from late-antique Neoplatonism, and were one of the many points of similarity between Gemistos and his accusers. From a Jewish or Islamic perspective – and doubtless also from Gemistos’s own perspective – there is a certain irony in a Scholarios or a Trebizond denouncing Gemistos for “polytheism”.

The very oddity of these claims can serve as a reminder of the art which lay at the centre of Christian heresiology: To create new theological genealogies which could lend intellectual plausibility to their author’s social vision and political agenda. Heresiologists typically operated on the assumption that all the forces of evil sprout from a single diabolical root and, hence, that everything imperfect had a unified origin in Satan. Jews, Muslims, and heretics – the dog-whistles of Christian polemic – could thus be given a part in any heresiological narrative, where they were often imagined collaborating with and inspiring one another. Everybody whom a heresiologist identified as worthy of censure was, in principle, likely to be in league with the rest of Satan’s forces, actively co-producing the downfall of Christianity. In this genre, rival Christians whose theology differed trivially from the heresiologist’s own were given grandiloquent genealogies which went back through primal Christian heresiarchs, Muslims, Jews, and pagans, to the Devil himself. The perplexing appearance of Judaism and Islam in these attempts to grapple with the Neopagan theology of Gemistos Pletho attests to the enduring grip of these phantasmic Jews and Muslims on the heresiological imagination.

Gemistos the Pagan Heresiarch and a Platonic Apocalypse: A Renaissance Co-Production

Trapezuntius’s vision of Gemistos Pletho as the latest in a succession of Platonic heresiarchs was a religious co-production that wove Gemistos’s radical pagan Platonism into a completely different intellectual framework, borrowed from the Christian heresiological tradition. This involved a new take on the widespread (and positive) view of Gemistos as a “second Plato”.

In the 1420s, before the onset of his deep loathing of Platonism, Trapezuntius himself had praised Cicero as “another Plato” (alter Plato), in precisely the same terms that Bessarion, Ficino, and many others would later use for Gemistos. In the 1450s, however, Trapezuntius set out to reverse the valence of this idea. He reframed the communis opinio – which Gemistos “Pletho” himself had encouraged – by embedding it in the medieval heresiological framework, tailored to make Platonism into the eternal enemy of Christianity, now finally unmasked as the inspiration behind Islam. Gemistos’s revival of Platonic paganism was then mixed with Trapezuntius’s own eschatological convictions to create a new, co-produced panic: that the fall of Constantinople was the first stage in a Platonic-Islamic apocalypse which could only be stemmed by the swift suppression of Trapezuntius’s enemies – and the urgent acknowledgement of the superiority of his translation of Aristotle’s Problems.

Sources and Further Reading

Bacchelli, F. 2018. ‘Gemisto Pletone, Demetrio Rhaoul Kavàkis ed il culto del sole’, in F. Muccioli and F. Cenerini (eds), Gli antichi alla corte dei Malatesta. Echi, modelli e fortuna della tradizione classica nella Romagna del Quattrocento (l’età di Sigismondo). Atti del Convegno Internazionale, Rimini, 9-11 giugno 2016. Milan, 591–613.

Ellis, B. A. 2024 ‘Neo-Pagan Censorship and Editing in Medieval Sparta, Or: How Gemistos Pletho Rewrote his Herodotus,’ Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Papers 78: 315–54.

Hladký, V. 2014. The Philosophy of Gemistos Plethon. Platonism in Late Byzantium: Between Hellenism and Orthodoxy. Farnham.

Monfasani, J. 1976. George of Trebizond: A Biography and a Study of His Rhetoric and Logic. Leiden.

Monfasani, J. 2021. Vindicatio Aristotelis: Two Works of George of Trebizond in the Plato-Aristotle Controversy of the Fifteenth Century. Tempe, AZ.

Woodhouse, C. 1986. George Gemistos Plethon. The Last of the Hellenes. Oxford.