Jillian Stinchcomb , 2023

His Mother, the Queen of Sheba: A Case of Religious Co-production

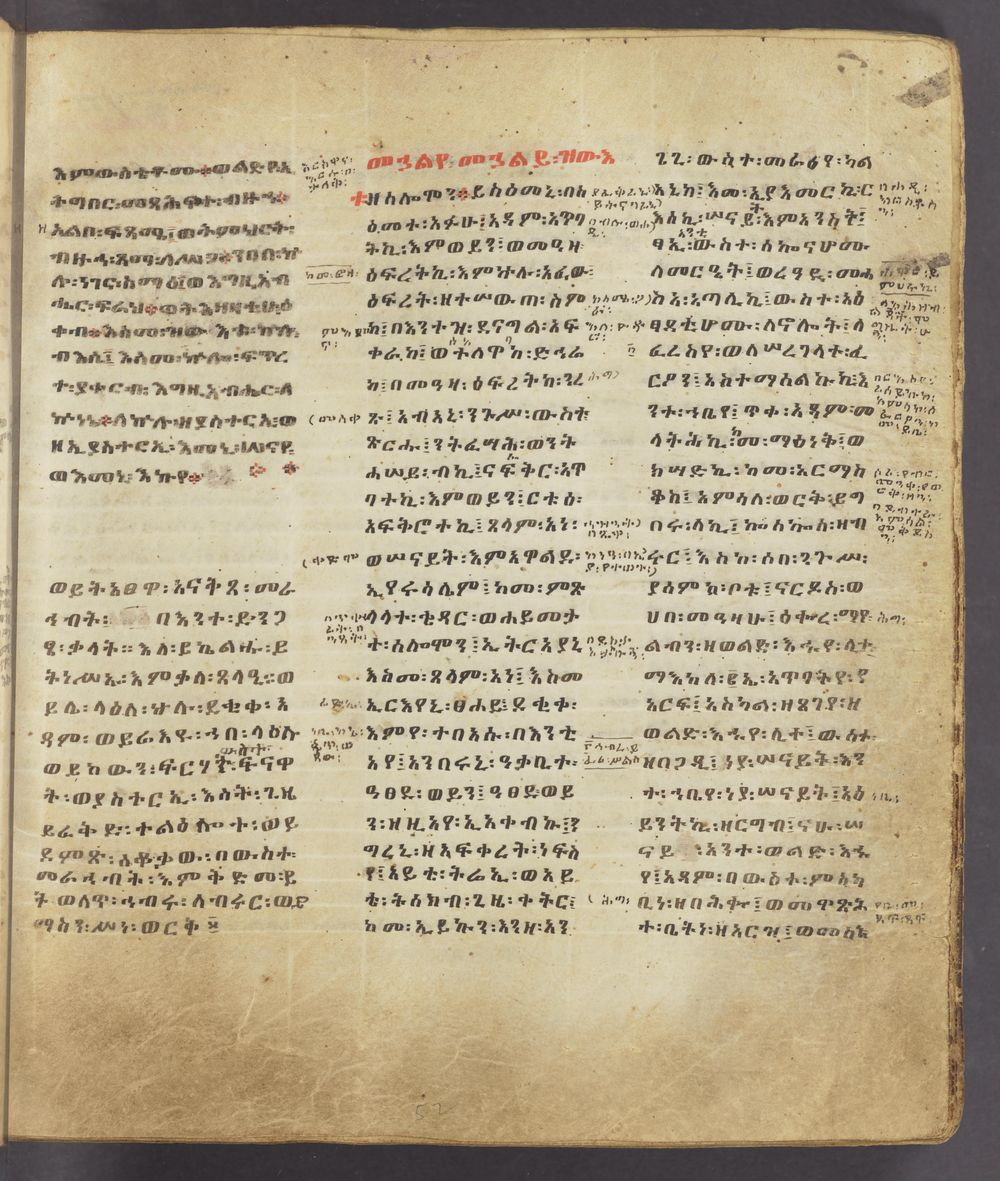

52r of the MSS Garrett Ethiopic Manuscripts no. 7, Princeton University Manuscript collection

The Queen of Sheba is a rarity: a non-Israelite woman who is a part of the scriptures of Judaism, Islam, and Christianity. The Queen of Sheba is best known for her visit to Solomon's court in the height of his rule. This visit is depicted in 1 Kings 10:1-13, 2 Chronicles 9:1-12, and Qur'an 27:15-44. The visit is also mentioned briefly in Luke 11:31 and Matthew 12:42. Post-Qur'anic interpretations of the Queen of Sheba are remarkably heterogeneous, with a variety of motifs, themes, and characters associated with her visit. My current project explores the formation and early reception of the Queen of Sheba from the biblical texts to the medieval Ethiopian epic the Kebra Nagast. In this case study, I explore two important premodern texts where the Queen of Sheba is presented as a mother of a child borne to her and Solomon, which reveals mutual influence and anxieties around the porousness of boundaries between Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities. Narratives of the Queen of Sheba as a mother show that the Queen of Sheba was co-produced between Jewish, Christian, and Muslim tradition, and that this co-production was a continual process. This case study opens interesting issues of temporality, as the biblical past was constantly re-made in moments of creative engagement with it.

Who was the Queen of Sheba?

We know remarkably little about the "real" Queen of Sheba, who is best known for visiting Solomon at his court at the height of his rule, which is generally dated to the 10th century BCE. We have no contemporaneous evidence of her existence, nor for that matter for Solomon's reign, and the earliest sources which mention her are the biblical texts of 1 Kings 10:1-13 and 2 Chronicles 9:1-12, which post-date Solomon's rule by centuries.

In the biblical narratives, the Queen of Sheba hears reports of Solomon's wisdom, comes to Jerusalem with a great train of spices, gold, and jewels in order to test him with hard riddles (1 Kings 10:1-2, 2 Chronicles 9:1) learns from him the answers to all of her questions (1 Kings 10:2-3, 2 Chronicles 9:1-2), views and praises Solomon's household (1 Kings 10:4-9, 2 Chronicles 9:3-8), exchanges gifts, and then returns home (1 Kings 10:12-13, 2 Chronicles 9:11-12). The audience is not informed of her name or anything about the land of Sheba, nor are we told what riddles she used to test Solomon or what questions he was able to answer for her. The text leaves a loud silence around the possibility of a romantic entanglement between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba: while there is a remarkable intimacy between the monarchs, signaled by the Queen asking Solomon "all that was in her heart" ( כָּל-אֲשֶׁר הָיָה עִם-לְבָבָהּ) and Solomon answering everything she asked, the text never explicitly suggests that the two had an erotic encounter with one another, and underscores instead the episodic nature of her visit: she hears reports of Solomon, comes to visit, and the text concludes with a note that she returned to her own land ( וַתֵּפֶן וַתֵּלֶךְ לְאַרְצָהּ, הִיא וַעֲבָדֶיהָ).

Despite the paucity of early evidence for the historical figure, or perhaps because of it, there is a wealth of later traditions that blossomed around the Queen of Sheba. Particularly in the post-Qur'anic period, we see a flowering of narratives about the Queen of Sheba for which we have no earlier evidence. These later traditions became so enmeshed with earlier ones that their relative youth was easily forgotten. One such motif is that of the Queen of Sheba as Solomon's romantic partner and mother of his child.

Recent research by Arnold Franklin suggests that, although genealogical discourses existed in the Hebrew Bible and antiquity generally, new attention was paid to genealogical links in the Islamicate period by Jewish communities, likely in response to Muslim concerns about the family of the prophet Muhammed. It is perhaps due to this intensified interest that discourses of the Queen of Sheba as a mother emerge at the end of the first millennium CE.

Two of the earliest sources which assert that Solomon and the Queen of Sheba had a child are the Alphabet of Ben Sira, a Jewish text from the ninth century CE, and the Kebra Nagast, an Ethiopian Christian text from the fourteenth century CE. Both of these texts, like the image of the Queen of Sheba they portray, emerge from the co-production of the biblical past in the course of much later Jewish, Christian, and Muslim discourses. Both are written for a specific community, utilizing elements of intra-confessional polemic to fortify communal identity. Both tell of a child, one who was not raised in Jerusalem and became the ruler of a different polity. Beyond this, however, the two texts are quite distinct, and thus offer a useful lens into some of the ways the biblical past can be re-produced by communities seeking to define themselves through their shared histories.

The Kebra Nagast and the Alphabet of Ben Sira

The Kebra Nagast was written to legitimize the rule of the Solomonic dynasty, which ruled the region until the 20th century. In the earliest manuscripts, there is a colophon stating that the text was translated from Arabic in the thirteenth century. Extant manuscripts date from the fourteenth century and later. The nominal focus of the text is on the early kings of Ethiopia, but it is clearly shaped by concerns dictated by Ethiopia's medieval history, especially the rise of the Solomonic dynasty in the 1200s after centuries of rule by the poorly documented Zagwe dynasty. It is written for an audience of Ethiopian Christians, inasmuch as it justifies their political and religious hegemony. The Kebra Nagast asserts that the Solomonic dynasty were the historic and true rulers of the region and provides a world history to attest to this fact. In a text of some 120 chapters, 40 or so are devoted to the visit of the Queen of Sheba, now named Maqedda, and to the aftermath of that visit. Particular attention is paid to the philosophical conversation between the two monarchs, the subject of less than a verse in the texts of Kings and Chronicles, but which receives pages of elaboration in the Kebra Nagast. The Queen of Sheba is here presented as an unambiguously intelligent, and self-possessed woman.

She is also presented as an object of Solomon's desire. Though the sexual propriety of the queen is stressed in the text, the monarchs have intercourse because Solomon exploits a promise she makes to take nothing from his household without his permission. He deliberately feeds her spicy food without offering her water. when she gets up in the middle of the night to drink, he accuses her of breaking her promise, and requests a sexual relationship as recompense. While we can and should look askance at the issues of consent raised by this episode, the text views the result of this encounter positively. the Queen of Sheba becomes pregnant and bears a son named Menelik I after returning to Sheba. Menelik is described as the first king of the Solomonic dynasty, and he eventually visits Solomon at his court. Solomon is so impressed by Menelik that he offers him, as his first-born, the kingdom of Israel, but Menelik insists that he must return to his homeland and his mother's court. Solomon sends him home accompanied by the first-born sons of the priests and nobles of Israel. The son of the high priest takes the Ark of the Covenant with him on this journey and Solomon is unable to recover the Ark. The text avers that the youths established a new Israel in Ethiopia as the true inheritors of the promises made to David and Solomon. In the Kebra Nagast, the Queen of Sheba's motherhood engenders the leader of a renewed polity and new claimants to God's promises to Israel, here viewed as the result of the meeting between a paragon of pagan philosophical wisdom (the Queen of Sheba) and Solomon, a paragon of godly wisdom.

The Alphabet of Ben Sira stands in contrast to this grand narrative. This text, which also presents the Queen of Sheba as the mother of Solomon's child, is the earliest extant parody written in Hebrew. It was produced within Jewish scholastic circles in Baghdad in the ninth century CE for an educated Jewish audience who would recognize the references to rabbinic literature embedded throughout the text. The text presents an anthology of stories and wisdom sayings, one of which is presented in alphabetical order (hence, the "alphabet"). The frame narrative of the text purports to tell the story of the life of the sage Ben Sira. Ben Sira is best known from the Wisdom of Ben Sira, a deuterocanonical text considered scriptural by many Christians but not a part of the Jewish scriptural canon. Ben Sira is mentioned only sporadically in rabbinic literature, suggesting that rabbinic audiences were aware of him as a figure but did not hold him in especially high esteem.

In the Alphabet of Ben Sira, the young Ben Sira becomes famous for learning all of Torah and Talmud by age seven, and the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar invites Ben Sira to his court. Initially, Ben Sira refuses the invitation, sending his response back on the entirely bald head of a rabbit. After a second invitation, he decides to visit Nebuchadnezzar's court and agrees to answer the king's questions. The first question Nebuchadnezzar asks is: how was Ben Sira able to render the rabbit's head entirely bald? Ben Sira responds: ask your mother. When pressed to elaborate, he explains that when the Queen of Sheba had visited Solomon at his court, she had lifted her skirts and revealed hairy legs. Solomon found her beautiful but disliked the hair, so he invented a depilatory of arsenic and lime. That depilatory enabled a sexual relationship between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, and Ben Sira claimed to have used the same one on the head of the rabbit he sent to Nebuchadnezzar, who was, according to Ben Sira, the product of that union.

This is an absurd proposition. It collapses the entirety of the book of Kings, which opens with the beginning of Solomon's rule and closes with the destruction of Solomon's temple in Jerusalem and the Babylonian exile, events for which Nebuchadnezzar was responsible. In addition to the absurdity of the temporal collapse, a well-educated Jewish audience would have found additional layers of humor in the story. The rabbit, for example, is the product of a complex multilingual pun based on a knowledge of Greek. The Ptolemies (who ruled Egypt after Alexander the Great) were known at the Lagai, and rabbits are lagoi in Greek, and the text renders the Queen of Sheba as an equivalent to the rabbit inasmuch are both are subjected to the depilatory in order to remove the hair from their bodies. It also suggests that she was the queen of Egypt, the area the Ptolemies controlled, and thus is foreign both to Solomon and to Nebuchadnezzar.

Somewhat surprisingly, Nebuchadnezzar accepts this explanation, with no objection to the idea that he might be the illegitimate child of an Israelite king and a Ptolemaic – which is to say, Greek-Egyptian– queen. He proceeds to ask Ben Sira a number of other questions which reveal the sage's wisdom and Nebuchadnezzar's foolishness. This is the last we hear of the Queen of Sheba in this text.

Queen of Sheba as a Mother

Both the Kebra Nagast and the Alphabet of Ben Sira are texts written for particular communities (Ethiopian Christians and well-educated Rabbanite Jews, to be precise) that produce visions of the biblical past that, at a minimum, creatively expand upon the Masoretic text. The Alphabet of Ben Sira creates a pastiche of biblical and rabbinic references, interwoven with folk tales which circulated in the Islamicate world, such as the famous Calila and Dimna. Both texts utilize traditions from Muslim, Jewish, and Christian communities, and utilize images of the Other in order to make their rhetorical points, whether that be in service of an argument for the chosenness of the Ethiopic Christian church or to make educated Jewish audiences laugh.

The texts generally, then, are products of a mixing of traditions between Jewish, Muslim, and Christian communities. An illuminating detail in this regard is the fact that the first place where the motif of the Queen of Sheba as a mother appears is in Islamic exegetical literature, beginning with the version of the Queen of Sheba's visit to Solomon's court in the Qur'an's twenty seventh surah. There, Solomon writes a letter to the Queen of Sheba, and before she visits, he requests that the jinn (supernatural beings) under his control bring her throne to his court and disguise it in order to trick her (27:38-41). She does not fall for the attempted deceit, but in the next verse, she mistakes a glass floor in his palace for water and lifts her skirts lest they get wet. Solomon informs her of her mistake, and in that moment she realizes that she has also been mistaken about the deity whom she worships, and decides to worship Solomon's God instead (27:44) – much like the Kebra Nagast. The ninth-century Muslim exegete and polymath al-Tabari found this passage puzzlingly laconic. He explains that the glass floor was also a trick, carried out by the jinn under Solomon's control. In his Tarikh (History), al-Tabari records a tradition that said the Queen of Sheba was a child of a king and a jinn, and the jinn whom Solomon controlled were afraid that if the Queen of Sheba and Solomon had a child, the child would rule the jinn forever (section 582-3). To avoid this fate, and limit the length of their servitude to only Solomon's lifetime, the jinn told Solomon that the Queen of Sheba had donkey legs underneath her skirt. According to this tradition, Solomon set up the glass floor in order to compel her to lift her skirts and reveal her legs.

The Kebra Nagast suggests that the progeny of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba would result in a centuries-long or even everlasting dynasty, the very thing feared by the jinn in the traditions al-Tabari cites. It also suggests the conversion of the Queen of Sheba, a motif first associated with the Queen of Sheba in the Qur'an. The image of the Queen of Sheba lifting her skirts, also first seen in the Qur'an, was obviously picked up in the Alphabet of Ben Sira. (Whether the Alphabet was directly influenced by al-Tabari, the traditions al-Tabari cites, or if it simply picks up a Qur'anic motif known in broader culture is difficult, if not impossible, to discern.) The Alphabet of Ben Sira does so in a text that engages with Christian truth claims, especially Christian engagement with Ben Sira as a scriptural figure. These connections between Jewish, Muslim, and Christian discourses suggest that we cannot locate the idea of the Queen of Sheba as a mother to a single tradition. Instead, we can percieve that the Queen of Sheba as a mother of Solomon's powerful children – whether staged as good, absurd, or evil – is a co-produced idea that developed not from one community but between the various discourses and truth claims made by competing and overlapping groups.

The "historical past" of scripture was a touchstone to Jewish, Christian, and Islamic communities alike. Of course, time marches ever onward, and communities cannot live in the past. But they could constantly re-make it, in the telling, re-telling, and reformulation of narratives about the past. Though there are no contemporaneous accounts of the Queen of Sheba's visit to Solomon's court, a Queen of Sheba who was very real to believing communities was often made and remade: new iterations, new narratives, new ideas were attached to her person. In this way, the Queen of Sheba acts as a useful lens on the heuristic of co-production, which insists not just on the early or originary moments of identity formation, but on the continued and continual re-creation of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim identities.

Wikimedia Commons, Lorenzo Ghiberti's Solomon and the Queen of Sheba engraving, found in the "Gates of Paradise" East Doors of the Florence Baptistery, bronze, from 1425-52

Further Reading

Belcher, Wendy Laura. 2009. “African Rewritings of the Jewish and Islamic Solomonic

Tradition: The Triumph of the Queen of Sheba in the Ethiopian Fourteenth-Century Text Kəbrä Nägäśt.” In Sacred Tropes: Tanakh, New Testament, and Qur’ān as Literary Works, ed. Roberta Sabbath, 441-59. Leiden: Brill.

Budge, EA, trans. The Kebra Nagast: the Lost Bible of Rastafarian Wisdom and Faith. 2020. Ed. Gerald Hausman. New York: St. Martin's Essentials, 2020.

-This text presents the EA Budge translation, which is out of copyright and available for free online. Unfortunately, this translation has major flaws; a new translation is forthcoming from Wendy Belcher.

Franklin, Arnold. 2012. This Noble House: Jewish Descendants of King David in the Medieval Islamic East. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mirsky, Jay and Stern, David, eds. 1998. Rabbinic Fantasies: Imaginative Narratives from Classical Hebrew Literature. Reprinted. Yale Judaica Series 29. New Haven: Yale University Press.

-This text includes an excellent translation of the Alphabet of Ben Sira.

Yassif, Eli. 1982. “Pseudo Ben Sira and the ‘Wisdom Questions’ Tradition in the Middle Ages.” Fabula 23: 48–63.

Yassif, Eli. 1984. Sippure Ben Sira bi-Yeme ha-Benayim. [Hebrew] Jerusalem: Magnes Press.