Yonatan Binyam , 2024

James Baldwin’s Meeting with Elijah Muhammad and the Co-Production of Religion and Black Identities in Twentieth-Century America

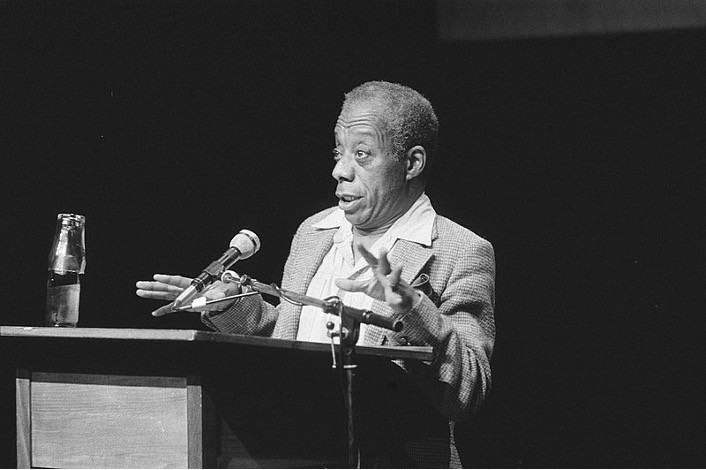

James Baldwin giving a lecture in Amsterdam on 2 December 1984. Photo by Sjakkelien Vollebregt. Nationaal Archief, Netherlands.

In their forthcoming article titled “Co-produced Religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam” (2024), Katharina Heyden and David Nirenberg call for a consideration of how the three religions have shaped and continue to shape racial imaginaries. This case study utilizes James Baldwin’s meeting with Elijah Muhammad as a framing device for discussing some early twentieth-century narratives of Judaism and Islam as reimagined through the prism of black racialized identities.

James Baldwin Meets Elijah Muhammad

In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin relates the story of his meeting with then leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, a meeting which occurred in the summer of 1961 in the latter’s mansion residence on the South Side of Chicago. Although he had never met him, Baldwin was acutely aware of Muhammad’s prominence within Nation of Islam circles and his reputation outside the movement as a radical and politically subversive leader. Prior to his meeting with Muhammad, Baldwin had even appeared on NBC’s The Open Mind hosted by Princeton professor Eric Goldman alongside the Nation of Islam’s most famous advocate, Malcom X. Both in his broadcasted appearances and in his writings, Baldwin defended the denunciations made by the leaders of the Nation of Islam against American society for its treatment of black people, although he strongly disagreed with their teachings on race and religion.

By the time he arrived at the house of Elijah Muhammad, Baldwin had garnered fame and acclaim as a writer and critic. Muhammad mentioned to Baldwin that he had seen him on television and that he appeared to be someone who had yet to be brainwashed and was still attempting to find his true identity. The twinned problems of finding one’s true identity and the danger of losing that identity to brainwashing by social forces served to bookend Muhammad’s explanations of the teachings and aims of the Nation of Islam. His message was predicated on the premise that racial identities could not be divorced from religious identities, as well as the claim that an authentically and essentially black identity could only be expressed through a natural, black religion. By contrast, Christianity was a false religion that African Americans had been brainwashed to believe by an oppressive white society.

Elijah Muhammad speaking at a gathering of the Nation of Islam members in 1964. Photo by New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer, Stanley Wolfson.

The problems of identity Muhammad posed to Baldwin touch on some of the key issues that gave rise to a number of new religious movements among black urban populations in the United States during the period between the two World Wars. During the first half of the twentieth century, northern American cities saw a significant demographic shift resulting from the influx of hundreds of thousands of African Caribbeans seeking better economic opportunities, as well as millions of African Americans seeking an escape from the poverty and racial oppression of the Jim Crow South. This demographic shift, often referred to by historians as the Great Migration, sets the socio-historical background for the emergence of what Judith Weisenfeld (2016) has dubbed “religio-racial movements” among black communities in northern cities like New York, Newark, Philadelphia, Boston, Detroit, and Chicago.

Baldwin himself notes the significance of the urban context for the emergent shifts in black identities. In the letter to his nephew that serves as a prologue to The Fire Next Time, Baldwin contrasts his nephew’s lack of religiosity with the piety of his grandfather (Baldwin’s father), who according to Baldwin had become so religious because he had been defeated and “really believed what white people said about him” (p. 291). Baldwin credits the relative absence of religiosity in his nephew to the fact that he was part of a new generation of black people who had “left the land” and escaped to “the cities of destruction.” Malcom X too considered his migration from rural to urban America as indispensable to his religio-racial awakening. He writes in his autobiography, “All praise is due to Allah that I went to Boston when I did. If I hadn’t, I’d probably still be a brainwashed black Christian” (p. 40).

The various religio-racial movements that emerged in northern cities were characterized by certain patterns of thinking about the dynamic relationship between race and religion in America. First, they argued for the inseparability of racial and religious identities at both the individual and societal levels. Second, they rejected American accounts of black people subsumed under the category of “the Negro” as a form of brainwashing and often viewed Christianity as playing a critical role in that brainwashing process. Third, these groups sought to reinscribe their racial identities through religious narratives drawn from Judaism and Islam. While they held some of these ideological tenets in common, these movements were not monolithic.

Religio-Racial Narratives and the Ethiopian Hebrews

Among several of the religio-racial movements that emerged in northern US cities in the context of the Great Migration were groups collectively known as Ethiopian Hebrews (or Black Jews or Black Israelites). Ethiopian Hebrew movements were constituted by organizations like the Beth B’nai Abraham Congregation and the Commandment Keepers Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation in Harlem. The Beth B’nai Abraham Congregation was established in 1924 by Arnold Josiah Ford, working together with Samuel Moshe Valentine and Mordecai Herman. Ford had emigrated to the United States from Barbados in the early 1920s before settling in New York, and his teachings on race and religion were heavily influenced by Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association, or UNIA. The Commandment Keepers Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation was founded by another African-Caribbean immigrant to the US named Wentworth Arthur Matthew, who had moved to Harlem from Saint Kitts in 1913.

While their teachings on race and religion were not identical, these Ethiopian Hebrew movements shared in common certain strategies for conceptualizing race and religion as two sides of a singular identity. For this purpose, they drew from narratives in various biblical and parabiblical sources that proved to be co-productive of both their racial and religious identities. For example, as the rabbi of the Beth B’nai Abraham Congregation in Harlem, Ford drew on stories from the Hebrew Bible to connect people of African descent with Abraham. He taught that in biblical times, Abraham’s place of origin, Ur of Chaldea, together with Africa and Arabia, was inhabited by Ethiopians (or black people) who were racially Semites.

Rabbi Arnold Josiah Ford and the choir of The Beth B’nai Abraham Congregation in Harlem, New York, ca. 1929.

Making connections to narratives about the Lost Tribes of Israel served as another strategy for identifying Africans with the ancient Hebrew tradition. In his book The Signs of the Times: Touching the Final Supremacy of the Nations (1903), a former teacher of Ford named J. Edmestone Barnes identified Africans as “the true Israelites.” He appeals to the account of the Lost Tribes who are exiled to Arzareth in the apocalyptic text 4 Ezra (or 2 Esdras) to buttress the claim that the identity of Africans as the true Israelites would be confirmed in the End Times.

Ethiopian history and literature also provided another source of inspiration for Ethiopian Hebrews, as their self-designated label indicates. Not unlike the similar narrativizing that takes place within the Rastafarian tradition, Ethiopian Hebrews connected their ancestral histories with stories about the royal dynasty in Ethiopia and its claims to preserving an unbroken line of descent from ancient Israelite royalty. For example, Matthew traced the ancestry of the Ethiopian Hebrews back to Menelik I, who according to the medieval Ethiopic saga known as the Kebra Nagast was the son of king Solomon and the Queen of Sheba and reigned as the first king in Ethiopian-Israelite dynasty that resulted from their union.

The rejection of dominant racialized narratives about black people and white people went hand in hand with the acceptance of Ethiopian Hebrew identity. Leaders like Ford and Matthew adamantly objected to being called “Negro,” since for them the term indicated a black person whose subjectivity was a byproduct of European brainwashing. This process, they believed, produced subjects who came to forget their own traditional roots, their original identities. At the core of these narratives was the recurring ideology that the Ethiopian Hebrew identity was an ancient one. Those who in the 1920s and 1930s converted to the movement saw themselves as not joining a new movement or adopting a new identity, but merely returning to their true, ancestral identity.

Another aspect of the co-production of race and religion within the Ethiopian Hebrew movements was the delegitimization of white, European Jewry. Although Ethiopian Hebrews did not express the same level of sharp invectives against white people as the Nation of Islam (as discussed below), their teachings did include narratives of European Jews that functioned to invalidate Jewish claims of descent from the ancient Israelites/Hebrews. Leaders like Ford taught that while Ethiopians (or black people) preserved the unbroken line of Hebrew descent tracing back to Abraham, the whiteness of European Jews was a marker of their intermingling with Gentiles (i.e. Europeans) after the Roman expulsion of some of the “Hebrews” to Europe. As a consequence, Ford considered the label “Jewish” appropriate for white Jews, while the term “Hebrew” was reserved for people of African descent.

Ethiopian Hebrew leaders also expressed various degrees of skepticism and rejection of Christianity as inappropriate for their followers, as can be seen in the movement’s gradual disassociation from Christian beliefs and practices. In the early days of the Commandment Keepers Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation in Harlem, for example, the organization expressed its beliefs in a hybrid form, partly Christian and partly Jewish. The congregation’s meeting place was adorned with Christian symbols like the cross juxtaposed with Jewish symbols like the Star of David and the use of Hebrew letters. Services were delivered in both English and Hebrew, lessons about Jesus being taught alongside instructions from the Talmud. Over time, however, the movement began increasingly to disassociate from Christianity, as exemplified in part by Matthew’s adoption of the title rabbi, replacing his earlier designations as elder and bishop.

Religio-Racial Narratives and the Nation of Islam

In contrast to Ethiopian Hebrew narratives of black people as “the lost house of Israel,” another movement emerged somewhat concurrently in the 1930s that refigured African Americans as “the Lost-Found Nation of Islam.” The paucity and biases of the earliest accounts of Wallace D. Fard’s work in Detroit make it difficult to reconstruct the group’s early history, since these accounts are limited to either the hagiographic stories from his later followers or the hostile reports about him contained in the files of the FBI. However, it is clear from the surviving record that Fard’s teaching promulgated a religio-racial message that placed black people and Islam at its core and depicted white people as the evil enemies of both.

Malcom X, who would go on to become the most famous and most successful evangelist of the Nation of Islam, summarizes the Nation of Islam’s early teachings, which drew on various elements from Jewish, Christian, and Muslim scriptures. According to a narrative called “Yacub’s History,” which was presented to Malcom as a key part of “the true knowledge of the black man,” African Americans were descended from the original race among humans who for centuries had lived in great empires and civilizations in Africa. These black people had also founded the Holy City of Mecca.

In contrast to the glorious origins of black people, white people were the evil creation of a rogue “scientist” named Mr. Yacub, a black man who had grown embittered toward Allah. Mr. Yacub was expelled from Mecca for causing trouble and exiled to the island of Patmos, the same place that John, the author of the Book of Revelation in the New Testament, was said to have received his apocalyptic vision. On Patmos, Mr. Yacub instituted a process of artificial selection, selecting for recessive genes manifesting in lighter skin. Over a period of six hundred years, the process resulted in the creation of brown, red, yellow, then finally white people with “blond hair, pale-skin, and blue eyes.”

Because the white people created from this unnatural process were “a devil race,” they began to wreak havoc in an otherwise peaceful world. As a result, the original black people rounded them up and marched them to the caves of Europe. Then Allah sent Moses to white people in Europe in order to civilize them. The first of the white people to accept the teachings of Moses were called Jews. According to a prophecy, the white race would rule the world for six thousand years. The prophecy also indicated that some of the original black people would be brought as slaves to North America, so that they might learn the evil nature of the white race firsthand.

This narrative about the origins of white people served as a counternarrative to accounts of “the Negro” that members of the nation of Islam adamantly rejected. For them, “the Negro” was the creation of “the devil white race,” which had cut black people off from their original language, religion, culture, and name. Where every other race in the world worshipped a god that at least looked homegrown, “the Negro” was forced to worship “an alien God having the same blond hair, pale skin, and blue eyes as the slavemaster” (p. 257). The slave masters employed Christianity to teach “the Negro” to hate everything black and to become a docile servant by learning to “always turn the other cheek.” Christianity also taught slaves to look to heaven in the next life for their rewards, while white people enjoyed their heaven on earth.

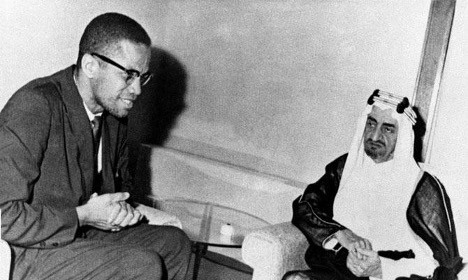

These narratives were presented to Malcom as the teachings of Wallace D. Fard, who had been God in human form. Malcom eventually rejected these teachings as false after his sojourn to Mecca in 1964 to perform the Hajj. He abandoned the Nation of Islam and converted to Sunni Islam, once again changing his name to el-Hajj Malik el-Shabbaz before he his assasination in 1965.

Malcolm X meeting with then Crown Prince Faisal Al-Saud in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in April 1964. Source: Saudi Press Agency.

Conclusion

While the growth of these religio-racial movements remained relatively limited in subsequent decades, some of the black Jews and black Muslims groups still exist today. In seeking to provide countervailing narratives to the dominant accounts of race and religion in America, these movements put certain Jewish and Islamic narratives to co-productive use in the construction of black identities that were at once both racial and religious. In doing so, they shone new light on how integrated Christianity had become with racializing narratives that often functioned to ascribe meanings to whiteness and blackness throughout American history. They further demonstrated the persistent appeals that narratives rooted in the ancient Hebrew or Israelite tradition held even for movements actively seeking to escape the racialized identities informed by Christian beliefs.

For Baldwin, the religious enterprises of groups like the Nation of Islam were equally as false and power-hungry as the white, Christian society they preached against. Baldwin ties the histories of both Christianity and Islam to their entanglements with political and imperial power. God and Allah, he remarks, had both “come a long way from the desert” (p. 313). God, heading north, had become white, and Allah, going in the opposite direction, had become black. Baldwin concludes that neither religion could provide black people with an authentically and essentially black identity, skeptical as he was of the very notion of becoming one’s true self. He writes about a similar anxiety over one’s identity that he perceived in white people whose sense of self-regard was anchored to a belief in the inferiority of black people. It seems that for Baldwin both groups were “trapped in a history” (p. 294).

As he prepared to leave Elijah Muhammad’s house, Baldwin was asked by Muhammad whether or not he belonged to any group. Baldwin said that he had left Christianity some twenty years earlier and had not joined any group since. He framed his answer in such a way as to indicate that he did not intend to join the Nation of Islam either. He then writes that he left Muhammad with things “heavily unresolved,” a phrase that succinctly describes the outcomes of the questions raised by twentieth-century religio-racial movements about the entangled histories of race and religion in America.

Further Reading:

Weisenfeld, Judith. New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Dorman, Jacob S. Chosen People: The Rise of American Black Israelite Religions. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Berg, Herbert. Elijah Muhammad and Islam. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

Clegg, Claude Andrew. An Original Man: The Life and Times of Elijah Muhammad. New York: Macmillan, 1998.

Baldwin, James. “The Fire Next Time.” In James Baldwin: Collected Essays, edited by Toni Morrison, 291–347. New York: Library of America, 1998.

X, Malcolm, and Alex Haley. The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley. New York: Ballantine Books, 1992.

Muhammad, Elijah. Message to the Blackman in America. Elijah Muhammad Books, 1973.