Sarah Islam , 2024

Lot’s Cave: A Co-Produced Pilgrimage Site Visited by Christian and Muslim Worshippers

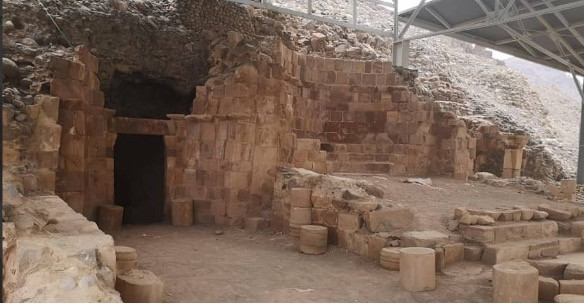

Stone door in modern-day al-Safi. © 2023, photo by author.

Introduction

Lot’s Cave near the Jordanian town of al-Safi, historically known also as Zoar, has been a site of veneration and pilgrimage for Christians—and later Muslims—for much of the past 1,500 years. Artifacts at the site indicate that the cave was a Byzantine Christian pilgrimage site from at least the fourth century CE. Even though the teachings of both faiths today discourage worship in settings with mixed religious symbology, archaeological evidence suggests that this was a shared place of veneration and pilgrimage for Christians and Muslims from the seventh to ninth centuries CE. It continued to be a site visited by Muslims (only) for two more centuries after that, after which the cave was entirely abandoned. The site was rediscovered in the twentieth century and is now visited by thousands of Christians and Muslims from all over the world.

Christian and Islamic Narratives

The Bible and the Qur’an offer overlapping but quite different narratives of Lot’s departure from Sodom. According to Genesis 19:1-38, two angels were sent by God to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. The angels urged Lot, who in the Christian tradition is viewed as a wise man but not a prophet, to take his family and leave the city, and not to look back at the ensuing devastation. Lot’s wife disobeyed this directive and looked back, immediately becoming a pillar of salt (Genesis 19:26). According to Genesis 19:22, Lot and his daughters traveled to the village of Zoar; fearful of remaining there, they decided to take residence in an isolated cave outside of the village (Genesis 19:30). In this same cave, Lot’s daughters devised a plan to get him drunk and commit incest with them in order to ensure the continuation of his bloodline, leading to the conception of the fathers of the Moabites and Ammonites (Genesis 19:31-38).

The Qur’an differs from the biblical narrative but concurs on some of the major details. It agrees with the general sequence of events in Genesis: the angels were sent to destroy both cities as divine punishment and Lot was commanded to leave with his family (Qur’an 7:80-82, 26:165-174, 29:31-35, 11:82). The Qur’an does not comment on what happened to Lot after his departure or where he went after leaving Sodom, making no mention of a cave or any specific location. Unlike the biblical narrative, the Qurʾan conceptualizes Lot as a prophet and his daughters as righteous. In Islamic theological discourse, it is inconceivable for prophets by virtue of their status as maʿṣūm (being infallible in terms of committing intentionally sinful acts) to commit what would be considered major sins, such as drunkenness and incest. Muslim exegetes such as Ibn Kathir and al-Qurtubi emphasize that the drunkenness and incest ascribed to Lot in the Bible would be impossible for such a righteous individual, and hence deny that it happened.

In terms of the site: from at least the tenth century onwards, many Muslim scholars have discouraged believers from visiting sites known to have been inhabited by divinely punished communities. Hence, visiting the Dead Sea, the coast upon which the cave is located and the area many believe to have been the location of Sodom has long been discouraged by many Muslim theologians (Ibn Hajar al-Asqalānī (d. 1449 AH), Fath al-Bārī, 6: 380). However, such prohibitions have not always dictated Muslim practice regarding the presumed site of Lot’s flight, which both Christians and Muslims were visiting toward the end of the first millennium CE.

The Cave of Lot as a Site of Pilgrimage and Veneration

The cave in which Lot is believed to have resided according to the biblical narrative has been identified with a cave on a steep mountainside at the southern tip of the Dead Sea, northeast of the Jordanian town of al-Safi, also often still referred to by its historical name of Zoar. This site seems to have functioned as a human sheltering space for over five thousand years. At its deepest excavated layer, archeologists have found burial sites and pottery jugs dating from the Early Bronze Age, 3300 to 3000 BC. Buried above this were a ceramic chalice and axe heads dating from the Middle Bronze Age, 1900 to 1550 BC, and above this were Hellenistic-Nabataean pottery jugs from the first century CE and Byzantine glass oil lamps from the fourth to sixth centuries CE. The cave floor, under which all of these items were excavated, dates to the Byzantine-ʿAbbasid period of the fourth to eighth centuries CE, on top of which ceramic items dating as recently as the ninth century CE have been found.

The cave is nestled within a complex constituting a water reservoir, church, and living spaces for monks and pilgrims, all structures which date from the Byzantine/early ʿAbbasid period. The reservoir is located on the south side of the complex, and the church on the north side. The basilica-church is triple-apsed, and its entrance is paved with four mosaics containing Greek inscriptions.

The mosaic towards the front-most area of the church is adorned with motifs typical of the early Byzantine period, including various birds, a peacock, lambs, and vines. As depicted in the image below, on the eastern end of the northern aisle is a four-line inscription mentioning the names ‘Bishop Jacobus’ and ‘Abbot Sozomenos’ and including the date, 606 CE.

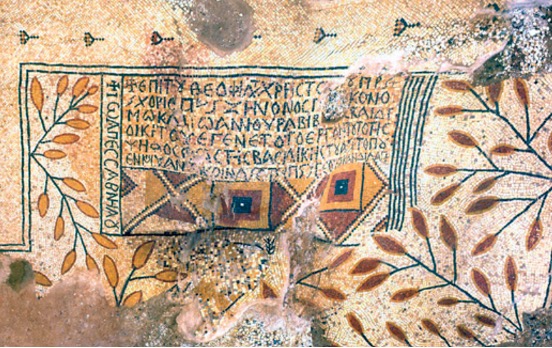

As depicted below, a mosaic located in the church nave is inscribed in Greek, naming the bishop as ‘Christoforos’, the presbyter as ‘Zenon’, and the governor as ‘Ioannis son of Rabibos’. The text states that the site is a basilica and dates its construction to May of 691 CE, naming the mosaicist as ‘Iannis, son of Sabinaou’.

To the left of this mosaic is a column with an inscribed invocation mentioning ‘Saint Lot’. The nave mosaic defines the site specifically as a basilica (Politis, 461-462). According to the excavators, the aforementioned names inscribed in the mosaics, many of which have been traced to historically known individuals whose identities correspond to and are verified in other sources, also attest to the existence of an active Christian community in that location in the late 7th century, well into the Umayyad era of Islam (661-750 CE).

As for the cave itself, it is located in the north aisle of the basilica. The cave entrance is flanked by pilaster capitals on the sides and a lintel above, with eight-cornered Maltese crosses and rosettes carved into them.

Upon entering, an Islamic prayer invocation in Kufic Arabic script, now mostly faded, is painted in blue pigment on the inside-facing portion of the right-side capital.

An Arabic inscription noting Qur’anic verses 37:133-136, which mention Lot’s status as a prophet and God protecting Lot and his followers from the destruction of Sodom, is carved into the stone towards the back of the cave. Both of the Islamic inscriptions have been dated by archeologists to the ninth century CE. A small room towards the back of the cave is paved with marble and is where Lot and his daughters are said to have resided after fleeing Zoar. At the bottom of the mountain, a few dozen meters away from the cave, is a modern-era mosque intended as a worship space for Muslim visitors, with windows facing the cave and basilica complex.

Archeologists examining eighth and ninth-century CE evidence at the site note that the space was likely accessible to and visited by both Christian and Muslim worshippers, even if in different capacities, given the temporal overlap of Islamic and Christian artifacts and inscriptions at the site that date to that era. The site was known to be a place of healing, with families bringing their ill to drink from a nearby spring and to pray at the site in hopes of a cure. The mixed symbology from the site’s Byzantine and Islamic eras is perhaps demonstrative of the fact that lay communities stressed religious boundaries far less than modern-day believers might expect, and that rituals and local cultural practices across communities and families passed over religious boundaries quite fluidly.

The mixed usage of the site between Muslims and Christians in the eighth and ninth centuries is perhaps not surprising. What is a surprising development, and what speaks to the co-produced nature of the site, is the fact that, after the cave was abandoned for a millennium, Muslims and Christians re-started the practice of visiting the site in contemporary times for the purpose of healing and veneration. In a contemporary context, one might expect Christians to be deterred by the presence of Islamic inscriptions signifying that control over the space was ceded to Muslim polities, to the degree that the only modern structure of worship located at the site is a Muslim one, a small mosque. As for Muslims, there are no scriptural indications pointing to the sacred nature of this specific site, and what the Bible says occurred at the site would be deemed blasphemous to affirm about a prophet according to many post-classical (i.e. tenth century onwards) Islamic canonical theological texts.

Most importantly, given that Qurʾanic scripture has nothing to say about the cave, the view that the cave is a site worthy of visitation has most likely been based on the (Jewish and) Christian Bible and the historical practices of local Christian pilgrims. Though early Sunni exegetes made use of Christian and Jewish textual sources to contextualize Qur’anic verses, in post-classical contexts this practice became discouraged in Sunni scholarship with the canonization of the hadith tradition and Sunnization. Hence the act of visiting this site in contemporary times presents an interesting case of co-production, in which biblical indicators function implicitly as the premise for an act of veneration despite Islamic normative directives presumably discouraging such a practice.

Further Reading:

Ahmed, Waleed. “Lot’s Daughters in the Qur’an.” In New Perspectives on the Qurʾan, edited by Gabriel Reynolds. London: Routledge , 2011. Pp. 411-424.

Khouri, Rami. “Deir ʿAin ʿAbata.” In The Antiquities of the Jordan Rift Valley, edited by R. Khouri. Amman: Solipsist Press, 1988. P. 108.

MacDonald, Burton, and Konstantinos D. Politis. “Deir ʿAin ʿAbata: A Byzantine Church/Monastery Complex in the Ghor es-Safi.” LA 38 (1988), 287-295.

MacDonald, Burton, Geoffrey A. Clark and Michael Neeley. “Souther Ghors and Northeast ʿAraba Archeological Survey 1985 and 1986, Jordan: A Preliminary Report.” BASOR 272 (November 1988), 23-45.

Lowenthal, Anne. “Lot and His Daughters as Moral Dilemma.” In The Age of Rembrandt: Studies in Seventeenth Century Dutch Painting, edited by R. Fleischer and S. Munshower. College Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988. Pp. 13-27.

The Madain Project Jordan Archeological Archive, “Lot’s Cave,” accessed June 25, 2024, https://madainproject.com/lots_cave.

Negev, Avraham and Shimon Gibson. “Deir Ain Abata.” In Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land, edited by A. Negev and S. Gibson. New York: Continuum , 2001. Pp. 137-138.

Politis, K.D., H. Fiedler, R. Schick and A. Lowe. Deir ʿAin ʿAbata Excavation Notebook, 1988. Manuscript kept at the Jordan Department of Antiquities Registration Center.

Politis, Konstantinos. “Excavations at Deir ʿAin ʿAbata, 1988.” LA 38 (1988), 461-462.