Yonatan Binyam , 2023

The Conflicts Between Christian Aksum and Jewish Himyar in Pre-Islamic Arabia

Co-production is at times violently competitive, as can be seen when Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities scramble for territorial dominance over one another. This case study of the Aksumite Marib inscription of 525 CE outlines several episodes of violent conflicts that took place in South Arabia over the course of the sixth century, focusing on the wars between the Jewish kingdom of Himyar and the Christian kingdom of Aksum. It also analyzes the various discursive strategies of legitimation, resistance, and memorialization employed by the Christian and Jewish rulers involved, as they made competing claims to the ancient Israelite heritage.

Aksumite and Himyarite Monotheism in Late Antiquity

The seventh-century teachings of Muhammad and the resulting unification of disparate tribes in the Arabian Peninsula under the banner of a single, monotheistic religion is a well-known story. By contrast, the sixth-century episodes of violence between Himyarite Jews and Aksumite Christians fighting for regional dominance in South Arabia are less known, though they provided an important context for the emergence of Islam.

In line with broader religious trends that saw the increasing popularity of monotheism across numerous parts of the late-antique world, monotheistic cults began to emerge on both side of the Red Sea in South Arabia and the Ethio-Eritrean Highlands during the fourth and fifth centuries. As early as the late third or early fourth century, such cults were already being promulgated by the ruling class in Aksum, the ancient kingdom that arose in the Horn of Africa to dominate trading networks from India to Egypt. Additionally, Aksumite kings allied with the Roman empire routinely attributed their military victories to Greco-Roman gods like Zeus, Ares, and Poseidon on their monumental inscriptions and minted coins.

They continued this practice following the conversion of Roman emperors to Christianity in the fourth century, after which point Aksumite victory inscriptions almost invariably adopt Christian terms. In one fourth-century inscription ’Ēzānā, the first Christian king of Aksum, gives praise to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit for his military victory over the Nubian kingdom of Kush. In addition to claiming sovereignty over Nubian peoples, ’Ēzānā also proclaims himself king over the Himyarites, Raydan, and the Sabaeans inhabiting territories across the Red Sea. Despite his claims to South Arabia, the archeological record indicates that Aksumite control of that region had come to an end by the close of the third century (c. 270 CE), after some seventy years of Aksumite rule. The expulsion of the Aksumites from the Arabian Peninsula appears to have been driven by the rise of the kingdom of Himyar, which emerged as a regional power in South Arabia by subjugating and uniting neighboring kingdoms like Saba and Hadramawt.

Map of Aksum and South Arabia (6th century

Around the turn of the fifth century, a hundred years or so after the Himyarites first consolidated power in the region, their inscriptions began to propagate monotheistic beliefs rooted in Judaism, in contrast with the Aksumite turn to Christianity. Accounts written in Greek, Syriac, Ge’ez, and Arabic suggest that Jewish communities had existed in the Arabian Peninsula for centuries prior to the emergence of Himyarite Judaism. Although the presence of Jews in South Arabia would no doubt have played a role in this development if that was indeed the case, the circumstances surrounding the origins of a Jewish monotheism in Himyar remain veiled by the absence of evidence.

What is clear is that a rather abrupt and radical shift in the religious practices of the South Arabian elite occurs by the end of the fourth century, as indicated by the record of official Himyarite inscriptions after c. 380. The hundreds of inscriptions produced during the first four centuries CE in praise of the multiple gods of South Arabia are suddenly replaced by venerations of monotheistic titles given in unvocalized South Arabian script, such as ‘ln (“God”), B‘l Smyn (“Lord of Heaven”), and Rhmnn (“Merciful”). Furthermore, a number of distinctly Jewish theonyms, such as B‘l Smyn ‘lh Ysr[’l] (“Lord of the Sky God of Israel”), emerge in these inscriptions. Together with numerous other pieces of evidence for the prevalence of Jewish practices in late-antique South Arabia (e.g. a seal depicting a menorah), the historical record demonstrates that Himyarite monotheism was heavily influenced by Judaism, if not thoroughly Jewish.

The Marib Inscription of 525 CE

Moreover, several inscriptions from this period reveal multiple incidents of military conflict and competitive mythmaking between the Jewish kings of Himyar and their Christian rivals in Aksum. The focus of this essay is one such inscription, known as the Marib inscription, according to which a Christian-Aksumite king named Kālēb (or variously ’Ella Asbeha) invaded South Arabia in 525 CE, overthrowing the Jewish-Himyarite king Yūsuf As’ar Yath’ar (or variously Dhū Nuwās). The circumstances leading up to this conflict are recounted in Greek, Latin, Syriac, Ge’ez and Arabic sources, making it possible to reconstruct at least parts of the story behind this dramatic confrontation between two religions/kingdoms.

According to several Christian accounts, the immediate impetus for Kālēb’s invasion of Himyar was Yūsuf’s persecution of Christians living in South Arabia sometime in the year 523 CE. The Martyrdom of Arethas (originally written in Greek c. 560 CE and surviving through its Latin, Ge’ez and Arabic translations) relates that Yūsuf laid siege to the Christian city of Najrān before killing its inhabitants as part of a campaign to wipe out Christianity in the region. Epigraphic evidence of inscriptions dating to around 523 also attest to the persecutions of South Arabia’s Christians. These inscriptions further suggest that Yūsuf’s campaign against Christians in his realm included the killing of hundreds of Aksumites in the Himyarite capital of Zhafar and the blockading of the harbor of Mandab on the Red Sea coast to prevent an Aksumite response.

According to the Martyrdom of Arethas, Yūsuf sought an alliance with Persia along religious lines, given their mutual opposition to Christian states (i.e. Aksum and Rome). In 524, he sent a letter describing his massacre of Christians to be read at a conference held at Ramla, in which both Byzantine and Persian delegates were present. The Martrydom then relates that once news of the persecutions reached the emperor in Constantinople, namely Justin I (r. 518-527), he in turn sent a request to the king of Aksum (through the mediation of the patriarch of Alexandria), prodding him by the power of the Triune God to annihilate the Jewish king. While this polemical Christian account of the conflict between Aksum and Himyar should not be taken at face value, the claim that the regional rivalry was accompanied by Byzantine and Persian involvement is corroborated by other sources such as the History of the Wars by Procopius.

Ostensibly in response to the letter of Justin I, and no doubt eager to regain control of South Arabia and the important trade routes that flowed through it, the Aksumite king Kālēb wasted little time in marshalling a large army. Already in 518 CE he had conducted a military campaign in South Arabia and installed a Christian king in Himyar. But Yūsuf had gained control of the region after the king Kālēb had appointed died in 522.

Kālēb’s return to South Arabia in 525 for his second campaign proved fatal to Jewish rule in the region. According to the Book of the Himyarites, following his victory over Yūsuf Kālēb put to death a large number of Jews who refused to convert to Christianity. The Life of Gregentios further adds that he remained in South Arabia for three years, destroying Jewish sanctuaries along with the temples of the non-Jewish tribes in the region. In their place, he constructed Christian churches in numerous cities throughout South Arabia.

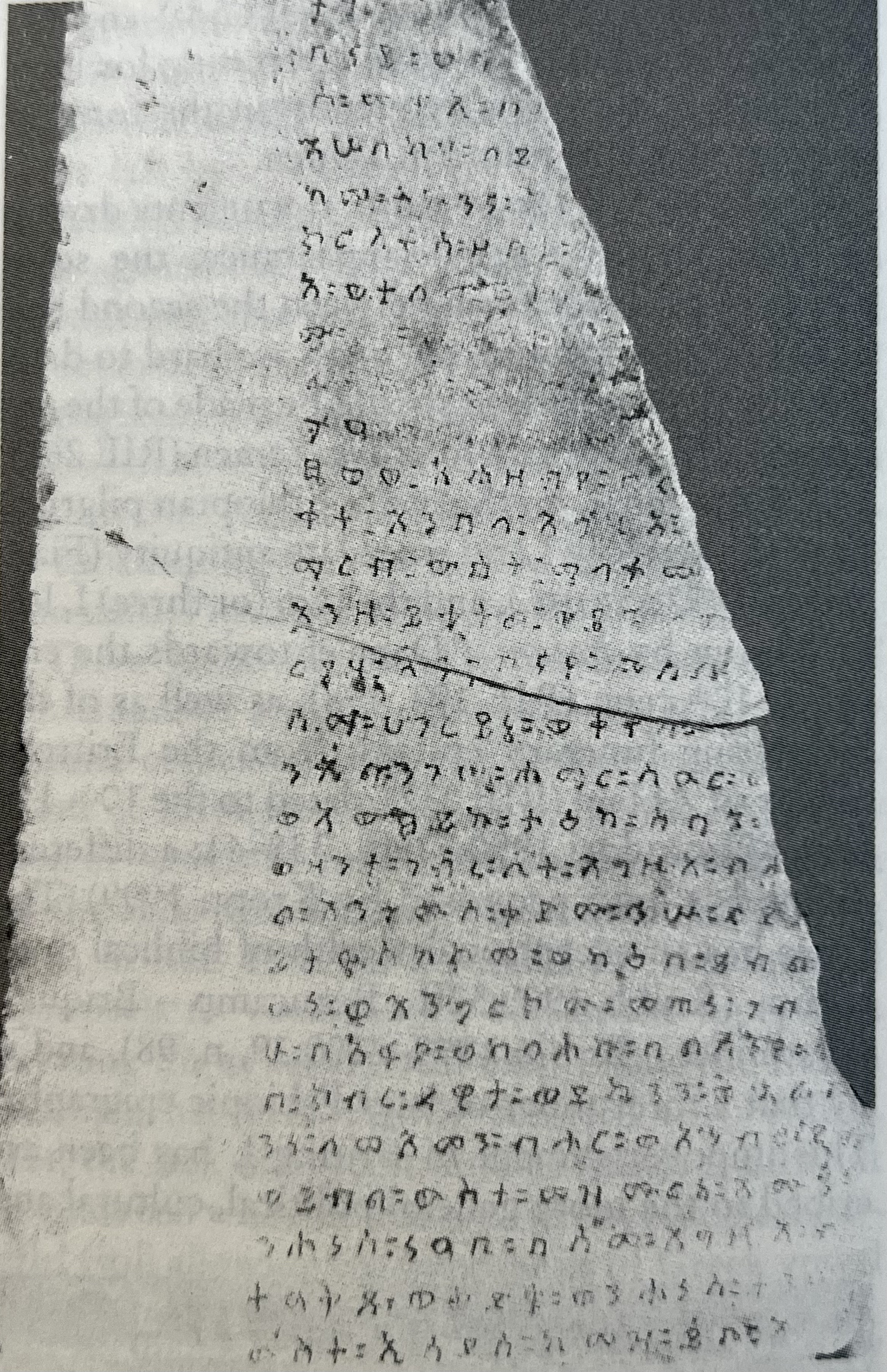

Whereas Kālēb had commemorated his first victory in Himyar by setting up a monument in Aksum, in 525 he erected his victory monument in Marib, a city in the Sabaean region of South Arabia. This Marib inscription is written only in the Classical Ethiopic (or fidal) script, breaking the Aksumite custom of composing victory inscriptions in Greek and Ge'ez, the latter typically written in both the Ethiopic (read left-to-right) and Pseudo-Sabaic (read right-to-left) scripts. Its monolingualism notwithstanding, the inscription reveals important themes about how Aksumite rulers sought to portray their place within the broader religious and socio-political narratives circulating throughout the late-antique world.

The Marib inscription of 525 CE. Ge’ez. From Encyclopaedia Aethiopica vol. 3, Siegbert Uhlig ed., Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiebaden (2007), p. 162.

The surviving fragments of the Marib inscription demonstrate Kālēb’s strategy for narrativizing the renewed Christian rule he sought to establish in South Arabia. The inscription is interspersed throughout with allusions to and quotations from both the Old and New Testaments. For example, lines 20-21 of the inscription draw from Matthew 6:33, and this line from the Gospels appears side-by-side with several passages taken from the Psalter, including Psalms 20, 66, and 68. One underlying motif connecting these passages is the idea that the people of God put their trust in him, and he rewards them by raising them up as victors over their enemies. This biblicized framing of Kālēb’s conquest over Yūsuf and the Jewish kingdom of Himyar serves to enshrine the Aksumite victory as tangible proof of the belief that Christians had replaced Jews as the true people of the God of the Bible.

The inscription contains another remarkable claim to the heritage of ancient Israel, making a direct connection between Kālēb and king David. The inscription refers to “the glory of David” (kebra dāwīt), a striking parallel to the expansive ethnomyth about the Israelite origins of Ethiopia’s royal family that appears in the medieval Ethiopic work the Glory of the Kings (Kebra Negast). The paucity of evidence for the early history of this important work precludes any conclusive statements about its relationship to Kālēb’s portrayal of himself in the sixth-century Marib inscription. However, it is striking that a legendary account of Kālēb’s reign is recounted in Chapter 117 of the Glory of the Kings, in which he is depicted not only as the protector of Christian realms, but also as the direct descendant of Solomon through the Queen of Sheba.

Whether or not the claim to the Davidic royal line etched on the Marib monument inspired the subsequent dramatization of that same narrative in medieval Ethiopia, both sources put certain aspects of the national epic of ancient Israel to the work of legitimizing Aksumite political rule. In the case of Kālēb’s inscription, which was deliberately erected in South Arabia rather than Aksum, the claim to “the glory of David” may have been promulgated as a response to the claims by the Jewish kings of Himyar that they represented “the People of Israel” (s‘bn Ysr’l), a title attested in several Himyarite inscriptions.

Although written centuries later, the Glory of the Kings similarly asserts that Ethiopia’s Christians have replaced Israel’s Jews as God’s chosen people. The parallels between the two sources might indicate that this distinctively Ethiopian iteration of the Christian replacement theology, characterized by its politicization of the biblical saga through its portrayal of Ethiopian kings as direct descendants of David, may have been circulating as early as the sixth century. If so, Kālēb’s Marib inscription may constitute an example of co-production where claims to Israelite peoplehood and Davidic kinship are no longer merely symbolic or theological. Instead, they function as actionable discourse for military and political domination over a territory of critical importance to the major imperial powers of the day.

The Aftermath of Kālēb’s Invasion of 525 CE

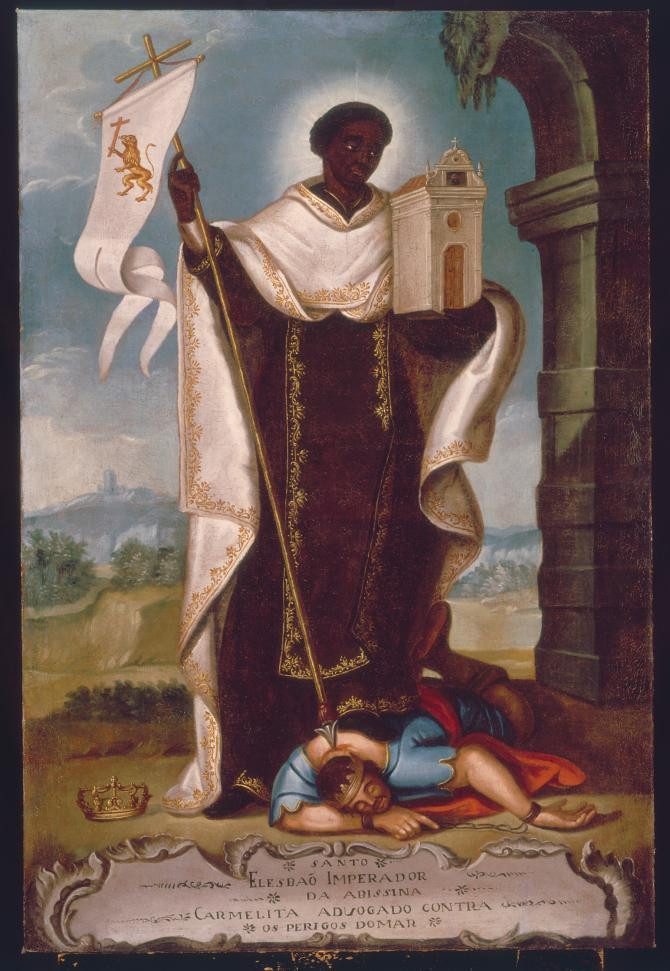

Not much is known about Kālēb after his second invasion of Himyar. The Ethiopian Synaxarium, wherein he is celebrated as a saint of the church, reports that after putting an end to the persecution of Christians in South Arabia he returned to east Africa, abdicated his throne, and lived the remainder of his life as monk. The Martyrdom of Arethas relates the same story, adding that after he took the monastic vow, he sent his royal crown to Jerusalem. These hagiographic accounts of Kālēb’s later years remain unverified, and there are no surviving mentions of him in any inscriptions or coins after 525. By contrast, his legacy as a protector of Christians lives on in the Ethio-Eritrean Orthodox traditions, having been expanded over the centuries in texts like the Glory of the Kings. In the early modern Catholic tradition he even becomes Saint Elesbaan, the Latinized version of his indigenous Ge’ez title, ’Ella Asbeha.

Saint Elesbaan, Anonymous, c. 1750. Oil on canvas (110 x 75 cm), Arouca, Portugal, at Museu de Arte Sacra.

In the aftermath of Kālēb’s conquests in South Arabia, Ethiopian kings continued to rule in South Arabia for a few more decades. The king Kālēb installed after his defeat of Yūsuf was himself quickly replaced by a more powerful Ethiopian Christian named Abraha. The latter rebelled from Aksum after taking control in South Arabia and subsequently managed to repel Kālēb’s attempts to overthrow the breakaway government.

Abraha’s short-lived successes in consolidating his power as the Christian king of South Arabia can be glimpsed from several of his inscriptions that have survived. One such inscription (also erected in Marib) reports that Abraha convened a conference for Byzantine, Persian, and Aksumite delegates, indicating that his regional government had garnered a level of recognition from the major powers of the day. Another inscription suggests that in 552 CE he launched a failed campaign to take control of central Arabia, which may have been the event that earned him the reputation in later Muslim accounts as the would-be conqueror whose attempt to destroy Mecca was thwarted by divine intervention.

The events surrounding the tenures of Kālēb and Abraha as rulers in South Arabia leave contrasting imprints in the Islamic tradition, since the legacies of the Jewish persecution of Christians and Abraha’s military campaigns have been memorialized in radically different ways in the Quran. On the one hand, Sūra 85 (sūrat al-Burūj) preserves elements of the persecution of Najrān’s Christians through the story of ‘Abdallāh ibn al-Thāmir, who is described as an imam put to death by Yūsuf. This Quranic passage evinces its dependence on Christian hagiographies of the martyrdom of Christians living under Jewish rule in South Arabia. It was ostensibly written as an example of how to remain resilient in the face of persecution, which would have been a powerful lesson for the early Muslim community, which in its nascent stages of formation was persecuted by the dominant tribes in Mecca (e.g. the Quraysh).

On the other hand, the story of the army defeated by God as related in Sūra 105 (sūrat al-fil, “The Elephant”) is read by later Muslim interpreters (e.g. al-Tabarī) as a reference to Abraha, whom they portrayed as unsuccessfully attempting to destroy the Ka’ba in Mecca, despite having a large army and war elephants at his disposal. This event is said to have taken place in “the year of the elephant,” traditionally identified in the Islamic tradition as 570 CE, the year of Muhammad’s birth. Although the traditional timeline does not align with the epigraphic evidence, it nonetheless sketches a poetic chronology wherein 570 simultaneously serves as the end of Ethiopian-Christian rule in South Arabia and the beginning of the story of Islam.

The Marib inscription of 525 CE opens a window into a series of confrontations between Christian and Jewish kingdoms perched on either side of the Red Sea. In their efforts to establish themselves as rightful rulers of South Arabia, the rulers of these kingdoms made competing claims to the heritage of ancient Israel, reinscribing the histories of Christianity and Judaism in the process. The strategies of legitimation, resistance, and memorialization they implemented, together with the political vacuum created by their wars on the Arabian Peninsula, helped shape the world out of which Islam would emerge.

Further Reading:

Grasso, Valentina A. Pre-Islamic Arabia: Societies, Politics, Cults and Identities during Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Bowersock, G. W. The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Hatke, George. Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient

Northeast Africa. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

Hatke, George. “Africans in Arabia Felix: Aksumite Relations with Himyar in the Sixth Century C.E.” PhD diss., Princeton University, 2011.

Robin, Christian Julien. “Ḥimyar, Aksūm, and Arabia Deserta in Late Antiquity: The Epigraphic Evidence.” Greg Fisher ed., (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015) 127–71.