Sarah Islam , 2024

Warith Deen Mohammed’s Exegesis of Surah Yusuf: A Contemporary Case of Sectarian Co-Production

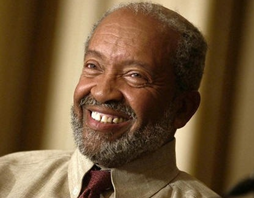

An image of Warith Deen Mohammed, son of the former leader of the Nation of Islam, Ellijah Muhammad (2010 - Public Domain; Wikimedia Commons)

Introduction

Warith Deen Mohammed (1933-2008), a twenty-first century African American Muslim theologian and son of Nation of Islam (NOI) leader Elijah Muhammad (d. 1975), is perhaps best known for his role in disbanding the NOI in 1976 to integrate his followers formally into the orthodox Sunni Muslim community. One of his best-known works in circulation today is his exegesis on Surah Yusuf, which he uses as a platform to discuss the legacy of American slavery and its long-term effects on the African American community: incarceration, crime, as well as low socioeconomic and educational attainment. In tackling a distinctly American historical topic, he pulls from multiple religious traditions in his exegesis to make his arguments, despite the fact that he has made it a point to shed syncretic and sectarian beliefs from his work so as to be viewed as an authentic mainstream orthodox Sunni religious scholar.

Instances of co-production in which another faith tradition is discussed in a positive light can be found in inter-religious contexts when a religious leader is looking to cement irenic relations between adherents of his own faith and those of another. In sectarian intra-religious contexts, however, we often find the opposite, namely the referencing of other religious traditions in a negative light to reinforce one’s own sectarian doctrine. Mohammed’s work is unique in this context. Though his work is meant for a Muslim audience, he nonetheless often makes reference to Jewish and Christian doctrinal material in a positive way in building his argument for the relevance of Surah Yusuf on debates regarding contemporary class and race issues.

Warith Deen Mohammed and the Nation of Islam

The NOI was an ethno-religious and black nationalist movement founded within the African American community by self-proclaimed prophet Wallace Fard Muhammad in the 1930s. Drawing upon both Islamic and Christian scripture and practices, Fard Muhammad would nonetheless develop a unique theological approach and philosophy of social activism specifically addressing the African American community, one which would be deemed inherently heretical by orthodox theologians of both of the aforementioned religious traditions. In an era in which ideas of scientific racism were widespread, Fard advocated for a type of black exceptionalism and racial separatism in African American communities that prioritized creating their own businesses, refraining from drugs and alcohol, and building more stable families. At the beginning of his ministry Fard was known to rely heavily on the Bible as his teaching text, later stating that his congregation’s familiarity with it made it an appropriate source for shaping his arguments. However, increasingly viewing Christianity as a tool of white supremacy and symbolic of America’s history with slavery, Fard would later come to center the Qur’an in his preaching. Adopting Arabic terms and certain Islamic practices, Fard Muhammad and his successor Elijah Muhammad developed a theology that framed this approach as reclaiming the long lost historic Islamic identity of their African ancestors, from which the legacy of American slavery had divorced them.

Fard Muhammad encouraged followers to adopt Muslim, Arabic-language names as a means of dis-inheriting surnames from their predecessors’ white slaveowners, to pray five times a day, and to adopt certain Islamic terminology in describing certain religious rituals and beliefs. The NOI often gave these terms significantly different meanings than were ascribed to them in Islamic scripture and theology. Contrary to the norms of Islamic theology, leaders of the movement did not adopt the five pillars, and claimed that God took on anthropomorphic forms, eventually claiming that Fard Muhammad was a manifestation of the divine. They moreover did not advocate belief in an afterlife. And, perhaps most importantly, they did not believe in the finality of Islam’s seventh-century era Prophet Muhammad, instead ascribing finality of prophethood to both Fard and Elijah Muhammad. Hence, while they selectively adopted certain Islamic concepts, Sunni and Shi’i orthodox theologians considered them heretical and blasphemous due to their central theological beliefs (and unbeliefs).

With Elijah Muhammad’s passing in 1975, his son and successor Warith Deen Mohammed inherited the mantle of NOI leadership and pursued wide-ranging reforms. He integrated his followers into mainstream orthodox Sunni Islam and was soon recognized by fellow Sunni theologians as legitimately Sunni. He rejected the deification of Fard Muhammad, characterizing him as someone who had taken advantage of the African American community. He also denounced the claims to prophethood of both Fard Muhammad and Elijah Muhammad, re-framed the group’s theological teachings to adhere to that of Sunni Islam, and re-trained the movement’s religious leadership to lead congregational worship according to the guidelines of Sunni precepts. Perhaps as a reaction to the deification of Fard Muhammad, Warith Deen Mohammed came to reject all forms of iconography and imagery in signifying the divine. On the activist front, he also renounced black nationalism in favor of an “Islamically” framed anti-racism that accepted other ethnicities, including white Americans, as fellow worshippers.

Warith Deen Mohammed’s Exegesis of Surah Yusuf

One of Mohammed’s most prominent monographs comprised his exegesis of Surah Yusuf. He uses this work as a platform from which to discuss the legacy of American slavery and its long-term effects on the African American community, namely incarceration, crime, and lower socioeconomic attainment. In attempting to demonstrate alignment with Sunni orthodoxy, he makes clear in his work his disavowal of syncretic or sectarian beliefs such as the divinity of Fard Muhammad. But his efforts to demonstrate his commitment to Sunni orthodoxy and disavowal of the aforementioned beliefs does not mean that his exegesis is free from outside influences.

In tackling a distinctly American historical topic, he pulls from multiple religious traditions co-productively to build his arguments. While Mohammed relies on Qur’anic scripture as the basis of his narrative, he includes allusions to Christian scripture and imagery in expounding his arguments. Though early Sunni exegetes made use of Christian and Jewish textual sources, this practice would later become discouraged in Sunni commentaries with the canonization of the hadith tradition and Sunnization. Hence, Mohammed’s exegesis presents a unique instance of co-production, in which a Sunni commentator re-directs the narrative to include not only Judeo-Christian imagery not depicted in Islamic literature, but also scriptural references from the Biblical tradition. In attempting to demonstrate his alignment with Sunni orthodoxy, he also engaged in a practice that runs counter to Sunni exegetical norms.

Mohammed relies on the Qur’anic narrative about Yusuf—to which all of Surah 12 is dedicated and named after—as a frame for his argument about the place of African Americans in American society. African Americans are dishonored in his era, he observes. As the progeny of slaves, they continue to be among the most socioeconomically disadvantaged, they lack equal opportunity for upward advancement, and they face injustice in the penal system. He notes that for many, particularly in the Christian tradition, this situation implies that African Americans are somehow inherently less deserving as lesser beings before God and that the social status of white Americans indicates that they are spiritually superior and deserve their worldly status (Mohammed, 20-27). He strongly rejects this narrative, using the Qur’anic narrative on Yusuf as his evidence. He points to the Qur’anic verses 12:4-21 which describe Yusuf’s plight when his brothers plot to kill him but instead leave him at the bottom of a well, after which he is picked up by travelers and subsequently enslaved. Yusuf was enslaved and endured dishonor in terms of his worldly plight, but this did not taken away from the true honor of his status before God (12:6-7), who elevated Yusuf’s spiritual status by designating him as a prophet. Yusuf held a high status with God but temporarily experienced a dishonorable place in the world; however, God restored his honor later in life (12:20-22). If African Americans choose a life of morality and virtue the way that Yusuf did, demonstrating fortitude and trust in God despite tribulations (12:15-18), Mohammed argues, God will restore their honor after temporary suffering, just as happened with Yusuf (Mohammed, 11-39).

Mohammed then turns to his argument on the subjugation of African Americans in the context of unjust imprisonment in the American penal system. Here he combines his analysis of the Qur’anic narrative of Yusuf with his critique of aberrant beliefs of prior NOI leaders. The wife of Yusuf’s master in Egypt attempts to seduce him but is unsuccessful in doing so (12:25-32). Though Yusuf is found innocent of any wrongdoing he is nonetheless sent to prison. His imprisonment is described in the Qur’an as a means through which God protected a beloved prophet from greater harm in lieu of a tribulation to be lamented (12:33-35). Mohammed compares this to the plight of African Americans. Egypt for Yusuf is what the United States is for African Americans. He argues that prior NOI leaders, in encouraging racial separatism, were actually playing into the hand of white supremacists favoring segregation. In doing so, they avoided unjust imprisonment by acquiescing to the demands of those in power. However, standing up for what is right, namely embracing a Sunni worldview in which all races are equal and integrated in spiritual unity, incites the displeasure of the dominant class. In doing so, African Americans fighting for equal rights and racial integration will challenge social hierarchies and inevitably end up facing unjust imprisonment and penal consequences as a result. Mohammed argues that, just like Yusuf’s unjust imprisonment, being unjustly imprisoned in the United States for maintaining one’s morality is not a sign of dishonor for African Americans; it is actually a sign of virtue, for which they will ultimately receive recompense from God (Mohammed, 26-35).

As mentioned above, early Sunni exegetes used Christian and Jewish textual sources, a practice later discouraged in the wake of the canonization of the hadith tradition and Sunnization. Post-classical Sunni scholars like Ibn Kathir (d. 1373) and al-Suyuti (d. 1505), for example, are known for cementing what would become the dominant trend in the Sunni exegetical tradition, namely relying only on what were deemed to be authentic hadith reports and sources internal to the Islamic religious tradition for commenting on Qur’anic scripture. It is therefore quite interesting that Mohammed, in the midst of his bid to be accepted within mainstream Sunni orthodoxy by denouncing conflicting beliefs that existed within the NOI, at the same time integrates within his exegesis excerpts from biblical texts to expound his arguments. For example, he points to Matthew 4:16, “the people living in darkness have seen a great light…,” to describe the trajectory of Yusuf’s life, from the darkness of the well to being saved by passersby and eventually obtaining a high rank in Egypt (Mohammed, 13-14). This emergence from darkness into light, he notes, also describes the potential for African Americans to emerge from their dark history into a more empowering future so long as they maintain their moral standards. Referencing Matthew 10:16, “…be wise as serpents, innocent as doves…,” he encourages his followers to lead with honest intentions but to adhere to the skills of the serpent, a cold-blooded animal that is slow to move. To succeed, the community must desist from reacting emotionally and instead be strategic in their efforts. He adds to this, taking John 3:14, “…just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the son of man be lifted up…” to support his view that, like the serpent in the wilderness, adopting strategic and intelligent approaches to communal policy issues would allow the entire black community to be lifted up in the long run (Mohammed, 150-156). Passionate responses, whether acquiescing to forbidden desires or being too hot-headed, are similar to brass that has lost its quality due to over-heating. Referring to Corinthians 13:1, he suggests that this resembles how people become like “tinkling brass,” devoid of quality material.

Mohammed uses Christian sources and norms not only to bolster his Qur’anic arguments, but also as a way to distinguish his own thinking from views he deems erroneous. In his analysis of Yusuf’s narrative, he likens Egyptian society to contemporary white American culture and Christianity. Just as Egyptians in Yusuf’s time would “pour out wine to drink,” with the implication that this often led to impropriety, so do contemporary American Christians permit alcohol, thereby promoting alcoholism among African American and Hispanic communities to enormous detriment (Mohammed, 26-39). He also likens former NOI leaders to those who would willingly do the bidding of Yusuf’s Egyptian masters and uphold societal hierarchies even if this were to lead to harm. By associating NOI leaders and Christians with the Egyptians, he ‘others’ both groups into one, separate and distant from his own theology. This serves his aim of distancing himself from earlier non-Sunni NOI theological positions.

His allusions to Christian doctrine are not limited to scripture but include imagery as well. In the Qur’anic story of Yusuf, an unspecified qamīṣ (shirt) soaked in blood is referenced as an item that Yusuf’s brothers use to try to convince their father that Yusuf was accidentally killed by an animal (12:15-18). The Qur’an makes no mention of any physical description of the shirt nor ascribes to it any special status. Qur’anic exegetes like al-Zamakhsharī (d. 1143), al-Bayḍāwī (d. 1319), Ibn ʿAṭiyyah al-Andalusī (d. 1147), and others, however, do make mention of the shirt being made of heavenly silk and point to narratives regarding its sacred origins, including traditions in which the angel Gabriel gifted the shirt to the Prophet Ibrahim, after which it was eventually bequeathed to Yusuf. Both Sunni Sufi and Shiʿi commentators such as al-Maybūdī (d. 1126) and al-Ṭabarsī (d. 1154) also point to the shirt’s talismanic status and protective powers; historians note that this belief contributed to the medieval Muslim practice of producing talismanic shirts. Surviving examples of talismanic shirts inspired by Yusuf’s garment with Qur’anic verses from Surah 12 embroidered into the fabric as a source of protection for the wearer can be found in Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal textile culture from the fifteenth century onwards. Such shirts were usually gifted to warriors for protection in battle, or worn by laymen for protection against the evil eye or black magic (Moghadam).The image below is an example of such a talismanic shirt from sixteenth century Mughal India.

Talismanic Shirt with Depictions of the Two Holy Sanctuaries, Mughal India or the Deccan. 16th or early 17th century. Material: ink, colored pigments and gold on cotton. Khalili Collection of Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage. Link here.

In terms of imagery borne from commentary, however, the Qur’anic exegetical tradition does not consistently link to the shirt any distinctive imagery beyond its being made of silk. Biblical narratives and commentaries very much do, however. Known most commonly as the ‘Coat of Many Colors’ and called the ketonet passim in the Hebrew Bible, the earliest narrative of the incident comes in Genesis 37. Jacob, as an apparent indication of favoritism, gives Joseph the ketonet passim as a gift (37:3). Joseph shares with his brothers two dreams wherein they bow down to him (37:5-10). Suspecting that the gift implies that Joseph is meant to assume family leadership, Joseph’s brothers become jealous and plot to have Joseph killed (37:18). The Septuagint, the third century B.C. Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, uses the word “poikilos” to define this coat, which implies the garment’s polychromatic nature (37:3). The seventeenth-century King James Bible takes this approach as well, defining the coat as one of “many colors,” as does the 1917 translation of the Jewish Publication Society.

Based on subsequent commentaries as well as artistic depictions, it is clear that the polychromatic quality of the garment became a defining physical characteristic in Judeo-Christian religious discourse. Famous historical depictions include an oil painting by Ford Madox Brown, commissioned by George Rae of Birkenhead in 1863, depicting the scene of Joseph’s brothers bringing a bloodied garment with pronounced multi-colored tatreez embroidery to their father. Another is seventeenth-century Austrian painter David Seiter’s work, titled “Jacob Gives Joseph a Coat of Many Colors.” Perhaps the most famous example contemporary to Mohammed would be depictions from Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s musical based on Joseph’s story from the Book of Genesis, “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat,” first performed in 1968. The musical would not only become popular in itself but would also popularize a rainbow-striped depiction of the ‘Coat of Many Colors’ that would also come to be adopted in Christian educational material for children as well as in the entertainment industry, such as in imagery associated with Dolly Parton’s 1971 album, “Coat of Many Colors.”

While Mohammed relies on the Qur’anic narrative as his basis, the imagery he includes, such as the image he uses in his exegesis below, distinctly reflects the polychromatic Coat of Many Colors in tandem with art inspired by Christian narratives, in particular the rainbow-striped depictions inspired by Webber and Rice’s work; the rendering embraces the Judeo-Christian imagery of the garment while at the same time adhering to the aniconism embraced by many Sunni Muslim scholars.

‘Coat of Many Colors’, image from Mohammed’s The Story of Joseph

Conclusion

Religious leaders looking to establish irenic relations across faith traditions in inter-religious contexts often engage in narrative or doctrinal co-production in which other faith traditions are discussed in a positive way. In sectarian intra-religious contexts, however, the opposite trend is often the case, namely pointing to other religious traditions in a negative light to stress the authenticity and veracity of one’s own sectarian doctrine. Mohammed’s monograph on Surah Yusuf is unique in this regard. Though his work is intended for an audience that understands itself as Muslim, he nonetheless chooses to include Judeo-Christian material in a positive and additive capacity as he constructs his argument for the relevance of Surah Yusuf on contemporary race and class debates. This integration produces fascinating results; for example, the rendering he uses of the ‘Coat of Many Colors’ embraces the Christian imagery of the garment while at the same time adhering to the aniconism embraced by many Sunni scholars.

In demonstrating his alignment with Sunni orthodoxy, Mohammed uses his exegesis on Surah Yusuf to disavow certain sectarian beliefs associated with early NOI leadership. In tackling a distinctly American historical topic, Mohammed weaves together doctrine from multiple religious traditions co-productively, relying on Qur’anic scripture for his base narrative but also on Christian scripture and imagery for his commentary. Through early Sunni exegetes used Christian and Jewish sources, this practice effectively disappeared with the subsequent canonization of the hadith tradition and Sunnization. Hence, Mohammed’s exegesis presents a unique case of co-production, in which a Sunni commentator, in integrating Christian material, engages in a practice that runs counter to Sunni canonical norms all while bidding for increased legitimacy within the Sunni fold.

Further Reading

Atighi Moghaddam, Behnaz. “Guest Post: A Warrior’s Magic Shirt.” Victoria and Albert Museum. Last modified June 17, 2015. Link here.

Berg, Herbert. Elijah Muhammad and Islam. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

Dewrell, Heath. “How Tamara’s Veil Became Josephs’ Coat: The Meaning of Ketonet Passim.” Biblica 97, no. 2 (2016): 161-174.

Hischak, Thomas. “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.” In The Oxford Companion to the American Musical. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Link here. Accessed June 20, 2024.

Koelb, Clayton. “Thomas Mann’s ‘Coat of Many Colors’.” The German Quarterly 49, no. 4 (1976): 472-484.

Mir, Mustansir. “The Qur’anic Story of Joseph: Plot, Themes, and Characters.” The Muslim World 76, no. 1 (1986): 1-15.

Mohammed, Warith Deen. The Story of Joseph. Chicago: WDM Publications, 2014.

McCloud, Aminah. “Imam Warith Deen Mohammed.” In Religious Leadership: A Reference Handbook, edited by Sharon Callahan, 2:649-652. Los Angeles: Sage Press, 2013.

Rudolph, Sarah. “How Colorful Was Joseph’s Coat?” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought 52, no. 2 (2020): 133-41.

Sahib, Hatim. “The Nation of Islam.” Contributions in Black Studies 13, no. 3 (1995): 48-113.

al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir. The History of al-Tabari: Prophets and Patriarchs. Translated by William Brinner. New York: State University of New York Press, 1987, 2:145-170, 3:165-180.

Wheeler, Brannon. Prophets in the Qur’an: An Introduction to the Qur’an and Muslim Exegesis. Sydney: Bloomsbury Press, 2002, 130-150.