Jillian Stinchcomb, 2023

Reine Pédauque: A now-lost Statuary Tradition as a Case of Religious Co-Production

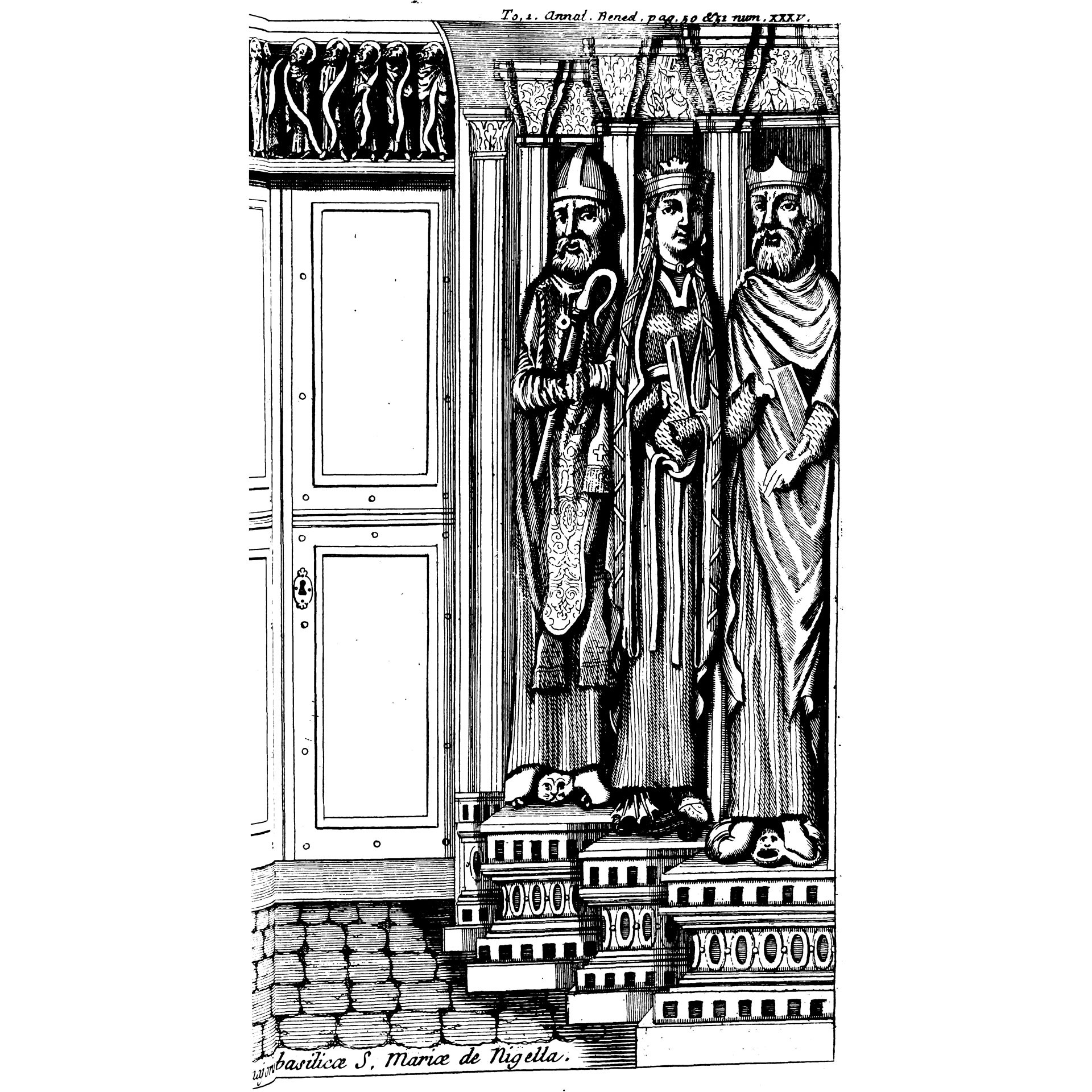

Mabillon, Jean. Annales Ordinis Sancti Benedicti. Tome I, Paris, 1703. Image taken from p. 51.

The Reine Pédauque represents a curious tradition: today, the term is perhaps most famously associated the Anatole France novel, "At the Sign of the Reine Pédauque," but it is also the name of several French boats and wineries. The relative popularity of this name is ironic, inasmuch as the referent of this tradition, the object(s) which are called "Reine Pédauque" no longer exist. Tracing the history of this term and tradition offers a fascinating case of religious co-production.

What is a "Reine Pédauque"? The term, perhaps from the late Latin "pes aucae" or the Occitan "pè d'auca," refers to a queen with webbed feet like a goose. Our earliest account of the term comes from the writings of Jean Lebeuf, who published in 1728 an account of his trip to Dijon, France, where he saw a statue of a woman with a crown and a webbed goose foot carved in to the doorframe of Saint Bénigne de Dijon church and learned the term "reine Pédauque" from the local villagers. Twenty-five years earlier, the scholar Jean Mabillon had already noted that the statue at Saint Bénigne de Dijon had three parallels in other 12th-century churches: Nesle-la-Reposte, Saint-Pierre de Nevers, and at Saint-Pourçain-sur-Sioule. In the decades that followed, a number of theses were proposed associating the "Reine Pédauque" with semi-historical figures, including the fifth-century Visigothic princess Austris, whose leprosy was cured when she converted to Christianity; Bertrade de Leon, an eighth-century noblewoman and foremother of French kings. Lebeuf had understood her as the Queen of Sheba, and current scholarship by French researcher Sylvia Cointot has come full circle in this assessment.

Unfortunately, all of the statues were destroyed by the end of the French Revolution. Modern research is based on drawings of the sculptures, leaving several open questions, not least why there appeared in the twelfth century several statues on churches which depict a queen with goose legs.

One crucial part of the answer is religious co-production: as Cointot notes, the motif is likely developed from Jewish or Muslim sources. The Queen of Sheba has long been known for visiting Solomon at the height of his rule as reported in the biblical books of 1 Kings 10 and 2 Chronicles 9. In the Qur'an, Surah 27 retells the story with details not included in the biblical narrative. One such detail is that when the Queen of Sheba visited Solomon, he was seated in a palace with a glass floor. She thought the floor was water, lifted her skirts, and inadvertently revealed her legs. This story is picked up in multiple strands of Jewish tradition. The ninth century Muslim polymath and exegete al-Tabari records a similar tradition, but there he includes a significant detail: there were rumors that the Queen of Sheba had donkey legs hidden underneath her skirts, rumors which are quashed when she reveals hairy legs instead.

European Christian tradition associated the Queen of Sheba with the Legend of the True Cross. In these legends, the wood of the True Cross had existed through time immemorial and was present for many significant moments in biblical history. In Solomon's time, it floated in a pool of water in his court; the Queen of Sheba steps into the pool of water in which the wood is floating, and her legs – donkey legs or legs deformed by illness, such as leprosy – are miraculously cured, leading to her conversion. Cointot suggests that the goose legs of the statues are linked to the legends of the Queen of Sheba having leprosy.

Much like the Queen of Sheba herself, of whom we have no contemporaneous evidence, the Reine Pédauque can only be known faintly, through representations that postdate the object under study by centuries. Similarly to the Queen of Sheba, the Reine Pédauque evinces the complex paths traditions can take, accumulating motifs and meanings as they pass through different communities. Considering co-production allows us to see the Reine Pédauque not just as a now-lost artefact which left linguistic traces on modern culture, but as part of a longer tradition of Jewish, Muslim, and Christian understandings of the rule of Solomon remembered and re-made over time. The Reine Pédauque, in turn, prods us to consider how many traditions and materials may have been lost over time, to understand our attempts at historical reconstruction as always-partial and participating in a stream of tradition that is deeper and richer than we can know.

Further Reading:

The fullest discussion of this phenomenon is found in:

Sylvia Cointot, "La Reine Pédauque en Bourgogne: Géographie et diffusion d'un type iconographique dans la seconde moitié du XIIe siè," Mémoires de la Commission des Antiquités de la Côte-d'Or, T. XXXIX 2000-2001, p. 127-148.

In English, this phenomenon is mentioned briefly and contextualized well in:

Barbara Baert, A Heritage of Holy Wood: The Legend of the True Cross in Text and Image trans. Lee Preedy (Leiden: Brill, 2004), especially chapter five.