Maria Lissek, 2024

Jacob Ben Reuben’s Milchamot HaShem: A Co-produced Christian-Jewish Dialogue

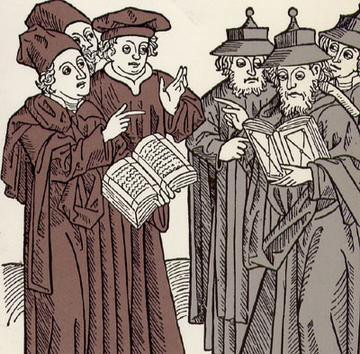

Woodcut carved by Johann von Armsheim (1483). Portrays a disputation between Christian and Jewish scholars (Soncino Blaetter, Berlin, 1929; Jerusalem, B. M. Ansbacher Collection; public domain).

While numerous Christian dialogues like this were written in the medieval Latin West, only one has been handed down from the pen of a Jew. Jacob Ben Reuben composed the Milchamot HaShem (מלחמות השם; 'Wars of the Lord’) before the end of the 12th century. This dialogue uses a conversation between a Jew and a Christian as a means of defending Jewish law and tradition and polemizing against Christianity. Reversing the model of Christian anti-Jewish dialogues, Ben Reuben presents a Jewish self-understanding in the face of and by using the Christian other. However, he does not simply copy the Christian model. Rather, Milchamot HaShem is a co-production that interacts with the Christian genre, apprehends Christian accusations – imagined as well as real – and adds its own characteristic features to the dialogue model.

In the prologue, Ben Reuben introduces himself as a Jew who was staying in Gascony (south-west France), where he met a well-known cleric. The two men maintained friendly contact, discussing the Christian and Jewish faiths and their mutual accusations. These conversations ground the twelve chapters that follow, in which the Jew and the Christian debate Christian doctrinal statements and anti-Jewish pronouncements. The Jew is called a ‘confessor’ and the Christian a ‘denier’ of the unity of God. The main part of the dialogue goes through various biblical books that the Christian, according to the Jewish protagonist, had used against the Jewish tradition (e.g., the Pentateuch, Psalms, Jeremiah, and Isaiah). The classic themes of medieval Jewish-Christian debate, such as the Trinity and monotheism, incarnation and messianism, all show up. The dialogue ends with two chapters that, in terms of content, represent a direct Jewish response to Christian statements of faith: Chapter 11 is a one long Jewish critique of the doctrine of the Gospel (האואנגילייוש; ha-evangeliosch), and chapter 12 explains why, according to Jewish understanding, the Messiah is thought not yet to have come.

While the introduction suggests that the conversation of the twelve chapters is a reproduction of the conversations between Ben Reuben and the cleric of Gascony, this direct reference is no longer recognizable in the dialogue: Ben Reuben clearly comments as the ‘author’ on the exchange between the conversing figures, Jewish ‘confessor’ and Christian ‘denier.’ In addition, the twelve chapters have a systematic structure which – although they retain the character of a dialogue – cannot be a record of the friendly meetings between the two mentioned in the introduction. The Christian figure falls completely silent in the last two chapters. Here only the Jewish figure speaks, devaluing the Christian faith and presenting Judaism as the true religion. In the end, neither of the dialoguing figures nor the authorial voice can represent the author’s sole perspective. Ben Reuben and his Jewish self-image in the face of the Christian other is reflected across the entire dialogue and thus in all its characters.

While Milchamot HaShem contains the characteristics of Christian literary dialogues, it also contains further characteristics that have no counterpart in the Christian model. For example, both prose and poetry are inserted by the author/narrator, introducing and commenting on the characters’ thematic arguments. Further, the Christianity of the work is a contemporary one (Christian dialogues usually assume a Judaism reflecting the Old Testament or the rabbinic tradition). Finally, Christian doctrinal concepts are translated into Hebrew (for example דיויניטאד, Divinitad/Theology), which is rarely necessary in Christian dialogues, since the Septuagint or Vulgate is usually the basis for their engagement with Judaism.

Ben Reuben was well aware of the polemics against his religion and its community; he mentions numerous figures within the tradition of Christian anti-Judaism by name: Jerome, Augustine, an unspecified Pablos, Gregory the Great. By the same token, he cites Jewish voices that had delegitimized Christianity, including Abraham ibn Ezra, Saadja Gaon and others. Thus, as the first known anti-Christian polemic in the Western High Middle Ages, written in a time when the Christian polemical dialogue was a well-established genre, Milchamot HaShem testifies to an informed and thoroughgoing engagement with established Jewish-Christian polemics that draws from both sides of that tradition to support the minority, i.e. Jewish, position.

Milchamot HaShem draws upon two specific Christian dialogues from the early-12th century, though they are not explicitly identified: the Disputatio Iudaei by Gilbert Crispin (1055–1117) and the Dialogus by Peter Alfonsi (11th/12th century). Ben Reuben reproduces statements from these dialogues in order to refute them, but will also add his own features to them to demonstrate Christian error. In this way, Milchamot HaShem turns these two Christian polemical dialogues on their heads: Christian, anti-Jewish voices become the mouthpiece for the presentation of the Jewish, and therefore correct, religion.

In creating a new Jewish genre out of Christian antecedents, Ben Reuben incorporates contemporary Christian texts into his dialogue, something that Christian dialogues are not known to have done vis-à-vis actual Jewish voices. While Christian polemical dialogues relegated Jewish religion to ancient Old Testament norms or a static rabbinic tradition, thus providing no real-world points of reference to contemporary readers, the Milchamot HaShem faces its contemporary adversaries head-on, utilizing Jewish and Christian voices to forge a self-confident Jewish identity with the once-Christian tool of the polemical dialogue.

Ben Reuben does more than copy the traditional anti-Jewish genre of the Christian polemical dialogue. He updates and improves it with new literary features and novel sources of content. Whether Milchamot HaShem invented or just represented the Jewish answer to Christian polemical dialogues in the 11th and 12th centuries, the work’s ingenuity illustrates that Jews actively participated in the ongoing intellectual exchanges (read: religious co-production) – both imagined and real – between Christians and Jews in the High Middle Ages.

Sources Cited:

Jakob Ben Reuben, Milchamot HaShem: Kriege Gottes, trans. Rolf P. Schmitz, Judentum und Umwelt 81 (Bern: Peter Lang, 2011).

Jacob Ben Reuben, Michamot Ha-Shem or Milḥamot ha-shem = מלחמות השם, ed. Judah Rosenthal (Jerusalem: Mosad ha-Rav Ḳuḳ, 1963).

Further Reading:

Berger, David, “Gilbert Crispin, Alan of Lille, and Jacob Ben Reuben: A Study in the Transmission of Medieval Polemic,” Speculum 49.1 (1974): 34–47.

Freudenthal, Gad, “Philosophy in Religious Polemics. The Case of Jacob ben Reuben (Provence, 1170),” Medieval Encounters 22 (2016): 25–71.

Lasker, Daniel J., “Controversy and Collegiality: A Look at Provence,” Medieval Encounters 22 (2016): 13–24.

Novikoff, Alex J., The Medieval Culture of Disputation: Pedagogy, Practice, and Performance (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

Rosenthal, Judah M., “Prolegomena to a Critical Edition of “Milḥamot Adonai” of Jacob ben Reuben,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 26 (1957): 127–137.