Yonatan Binyam, 2024

Jewish and Muslim Elements in the Christianized Ethiopic Alexander Romance

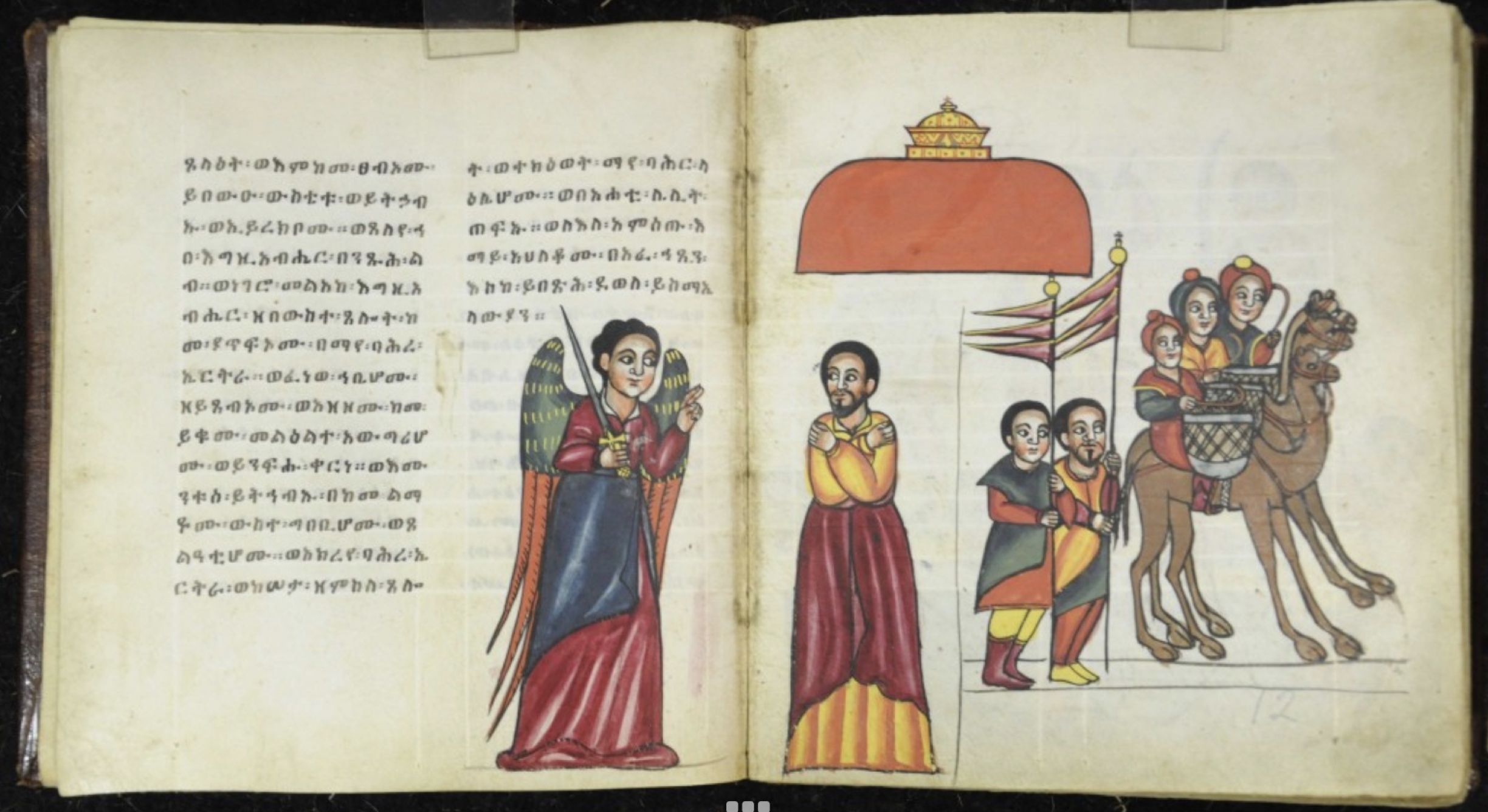

Illustration of an angel appearing to Alexander as he prays to God for guidance in his military compaigns. From a manuscript of the Zenā ʾƎskǝndǝr, i.e. MS HMML EMDA 00208, 18th century, from Goggam Province, Ethiopia, as catalogued and digitized in the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library in Collegeville, MN.

The Alexander Romance is a legendary account of the life and deeds of Alexander the Great, which was first written in Greek sometime in the third century CE. It is notable for its exceptionally widespread reception and frequent adaptations across numerous languages and cultures. The Ge’ez version of the Alexander Romance, commonly referred to as Zenā ʾƎskǝndǝr (or The History of Alexander), represents a thoroughly Christianized reworking of the Romance. The text was translated from an Arabic source sometime between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Arabic version itself, only fragments of which have survived, is dependent on a Syriac translation of the Greek Romance that was produced in the seventh century.

Due to the heavily fragmentary nature of the surviving textual witnesses to the Arabic text, it is not possible to reconstruct a clear picture of how much the Arabic contributed to the Christianization the Romance underwent in that faze of its transmission from the Syriac to the Ethiopic. Although the Syriac text contains some Christian features (e.g. a few veiled allusions to the New Testament), the text retains much of its Greek pedigree in its depiction of Alexander, who in the Syriac Romance continues to worship Greek gods like Zeus and Poseidon.

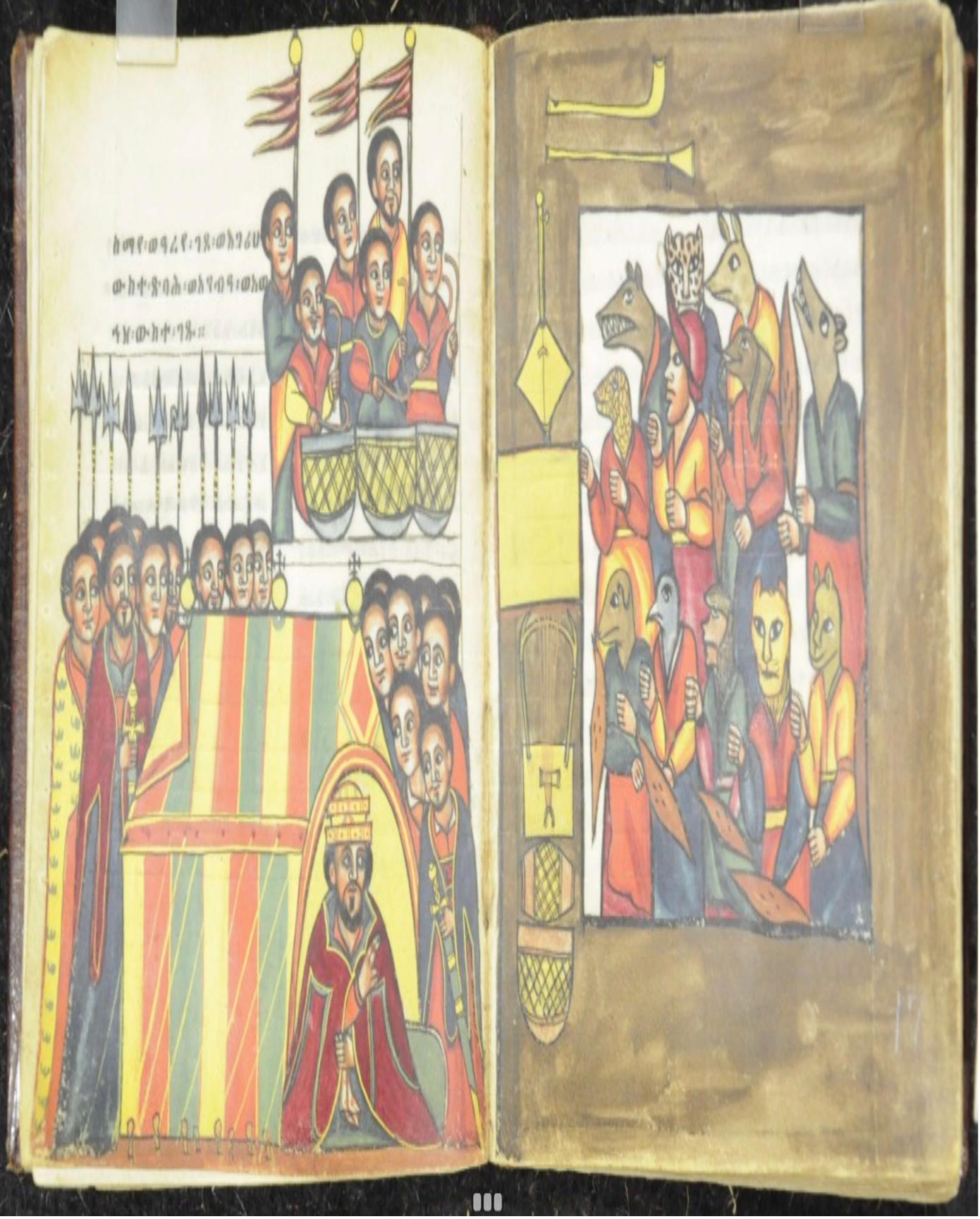

In the Ethiopic Romance, by contrast, Alexander is depicted as a faithful Christian from the outset. Before launching his campaign to conquer Persia and lands beyond, Alexander delivers several lengthy sermons to his followers regarding the evils of polytheism and idolatry. He also relates his conversion to Christianity, before instructing his hearers to worship the three persons of the Triune God. The Ethiopic Romance also incorporates stories taken from the Syriac Christian Alexander Legend, a short legendary account of the deeds of Alexander that includes the story of the wall Alexander builds to keep out the nations of Gog and Magog.

Illustrations of Alexander preaching and leading his troops into battle juxtaposed with the monstrified nations of Gog and Magog in the same manuscript of the Zenā ʾƎskǝndǝr as cited above (MS HMML EMDA 00208, 18th century, Goggam Province, Ethiopia, from the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library in Collegeville, MN).

In addition to its distinctly Christian features, the Zenā ʾƎskǝndǝr represents the culmination of a long transmission history of the Alexander Romance during which several Jewish and Muslim motifs are introduced into the tradition. With respect to Jewish influences, for example, the Ethiopic Romance includes the story of Alexander’s visit to Jerusalem, which is first related in Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities and several Rabbinic sources. In these accounts, Alexander enters the Temple in Jerusalem, recognizes the Jewish God as the one true God, and extends privileges to the Jews before his departure to fight Darius. This story eventually makes its way into the Alexander Romance tradition, the first interpolation of the episode appearing in an eight-century recension of the Greek Romance. The story also enters the Catholic literary traditions of Western Europe through the Latin translation of the Romance produced by Leo the Archpriest of Naples in the middle of the tenth century.

Moreover, the dynamic co-productive valences of the Alexander Romance traditions also appear in the Ethiopic text in its use of Muslim motifs, e.g. the Islamic title for Alexander as found in the Quran, namely Dhulqarnayn (or “The Two-Horned”). The figure of Dhulqarnayn appears in Sura 18 Al-Kahf (“The Cave”), which recounts Alexander’s travels to the most remote lands of the setting sun and his erection of a barrier to keep out the nations of Gog and Magog. The Quranic story is most likely drawing on the same traditions that inform the Syriac Christian Alexander Legend, given the similarities in the descriptions of Gog and Magog that appear in each text. The Ethiopic Romance in turn is clearly drawing from a source that is informed by both the Syriac-Christian and Quranic accounts of Alexander.

In conclusion, an analysis of the Zenā ʾƎskǝndǝr reveals several moments of co-production between Jewish, Christian, and Muslim reworkings of the Alexander Romance. The text illustrates how late-antique and medieval Jews, Christians, and Muslims borrowed and exchanged various stories and ideas about Alexander, with the aim of recreating the famous figure in terms that reinforced their respective theological frameworks.

Further Reading:

Stoneman, Richard. The Greek Alexander Romance. London: Penguin Books, 1991.

Klęczar, Aleksandra. “Alexander in the Jewish Tradition: From Second Temple Writings to Hebrew Alexander Romances.” In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Alexander the Great, edited by K. R. Moore, 379–402. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

Ciancaglini, Claudia A. “The Syriac Version of the Alexander Romance.” Le Muséon: Revue d’Études Orientales 144, no. 1 (2001): 121–40.

Zuwiyya, David Z. “Alexander the Great in the Arabic Tradition.” In A Companion to Alexander Literature in the Middle Ages, edited by David Z. Zuwiyya, 73–112. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Kotar, Peter Christos. “The Ethiopic Alexander Romance.” In A Companion to Alexander Literature in the Middle Ages, edited by David Z. Zuwiyya, 157–76. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

Doufikar-Aerts, Faustina. Alexander Magnus Arabicus: A Survey of the Alexander Tradition through Seven Centuries. Walpole, MA: Peeters, 2010.