Jillian Stinchcomb, 2024

Making Magic, Co-Producing Religion: The Magic Bowls from Nippur

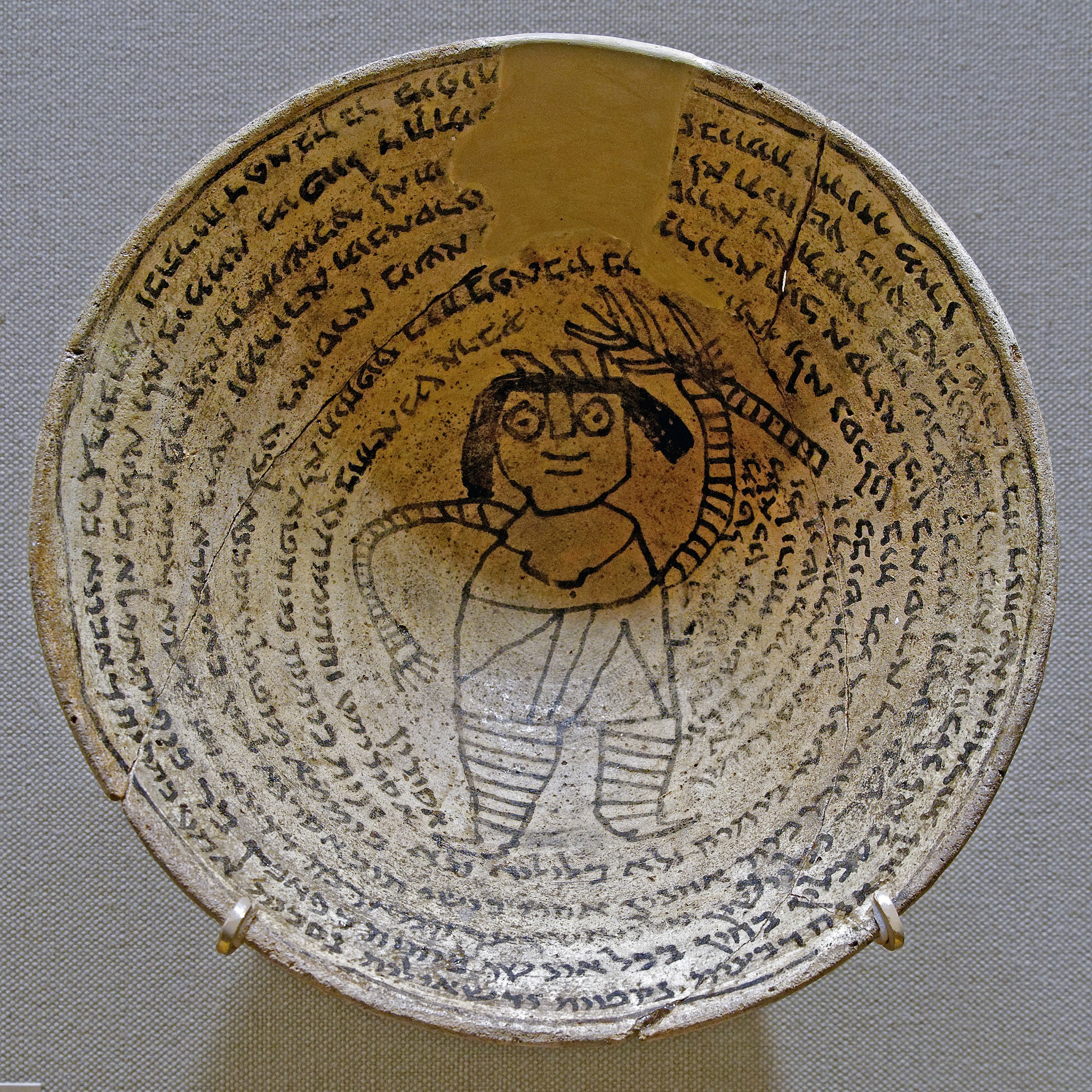

Example of a 6-7th century CE Incantation bowl from Nippur. Lent to the Metropolitan Museum by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Accession number L1999.83.3. (Wikimedia Commons)

Today, someone who wants a bit of extra luck might knock on wood, look for a four-leaf clover, or purchase a rabbit’s foot. In some parts of the ancient world, someone looking for good fortune might purchase what scholars today call a magic bowl. A magic bowl, sometimes called an incantation bowl, is an object made of fired clay which was inscribed with a magical incantation and ritually buried upside-down in the ground in order to trap a misfortune-causing demon. Sometimes the bowls included small drawings of a demon in the center of the bowl, like the one in the image of a bowl from Nippur above. Most incantations found in the bowls aim to procure protection, health, or blessings for the buyer.

Magic bowls have been found all over west Asia and today many can be found in private collections, notably the Moussaieff collection and the Schøyen collection. We cannot be certain of the provenance of the bowls in these collections, but similar bowls were discovered roughly 200 kilometers south of Baghdad in the ruins of an ancient city called Nippur by archaeologists in 1888–1889. They were deposited between the sixth and eighth centuries CE, when the area was ruled by the Sasanian Persian empire and populated by a variety of groups including Jews, Christians, and Mandeans, an ethnoreligious group that reveres Adam as its founding prophet and John the Baptist as the final and greatest prophet. Jews, Christians, and Mandeans in this part of the world all spoke Aramaic, but they wrote in different scripts and used slightly different dialects. Most of the magic bowls use a square script, associated with Jewish writing practices, but a substantial fraction deploy Mandaic script, used by Mandeans, and a third group of the bowls utilizes Syriac script, which is associated with Christianity.

Despite the differences in script, which one might expect to mark differences in religious expression, the bowls share many similarities. The buyers of the bowls are identified with their mothers’ names, rather than their fathers, as is standard in other texts. The phrases used on the bowls are legalistic in nature, suggesting a shared sense that demons could be constrained by the proper use of God’s juridical system. One might see this simply as evidence of certain characteristics common to these three religious cultures. But there is also explicit evidence of crossing between them. For example, one Syriac bowl known by the label CBS 16086 uses a legal formula of divorce that parallels not only in the Jewish bowl CBS 9010 but also a passage in the Babylonian Talmud found in tractate Gittin 85b. Furthermore, there is often a mismatch between the names of the buyers and the script used on the bowls, suggesting that Mandeans and Christians bought Jewish bowls, Jews and Christians bought Mandean bowls, etc.

One bowl in the Moussaieff collection, M163, uses the square script (associated with Judaism) but explicitly invokes Jesus and God his father as well as a mysterious, probably “pagan” (non-biblical) deity called Shamish. Examples like M163 and CBS 16086 demonstrate the impossibility of cleanly dividing the collection between Jewish, Christian, Mandean, and pagan examples; the people involved in the production and consumption of the bowls shared an assumption that bowls possess power and can be effective for gaining the desired results. At times the adherents to these different traditions seem explicitly to look to each other’s traditions for such power, such as M163 calling on Christian and pagan deities in Jewish script. The bowls offer us a glimpse of how some individuals practiced their religious beliefs and how these emerged in spaces where many different religious groups existed simultaneously.

The cultural phenomenon represented by the bowls, shared between Jews, Christians, and Mandeans, serves as a reminder that co-production emerges perhaps most vibrantly through lived practices of religion, especially in a practice like the bowls, which are produced by people living in close enough proximity to one another to share a common idiom or to have a mutual sense of what might influence one’s fortune. The religious experiences of the buyers and users of these bowls is created in part through the borrowing and appropriation of “outside” tradition. The very incorporation of these traditions makes them no longer external to the tradition and lived experience of ancient religious practitioners but rather an integral part in the continual process of the making of a religious tradition.

Further Reading:

Siam Bhayro, “Divorcing a Demon: Incantation Bowls and BT Gittin 85b,” in The Archaeology and Material Culture of the Babylonian Talmud, ed. Markham J. Geller (Leiden: Brill, 2015) 121–132.

Dan Levene, “And by the name of Jesus…” An Unpublished Magic Bowl in Jewish Aramaic, “Jewish Studies Quarterly” 6.4 (1999) 283–308.

Dan Levene, “Jewish Aramaic Incantation Bowls,” in Jewish/non-Jewish Relations: Between Exclusion and Embrace. An Online Teaching Resource.

Avigail Manekin Bamberger, “Jewish Legal Formulae in the Aramaic Incantation Bowls,” Aramaic Studies 13 (2015) 69–81.

Marco Moriggi, “Jewish Divorce Formulae in Syriac Incantation Bowls,” Aramaic Studies 13 (2015), 82–94.