Anthony Ellis, 2025

The Alba Bible: A Medieval Spanish Co-Production by a Rabbi and the Friars of Toledo

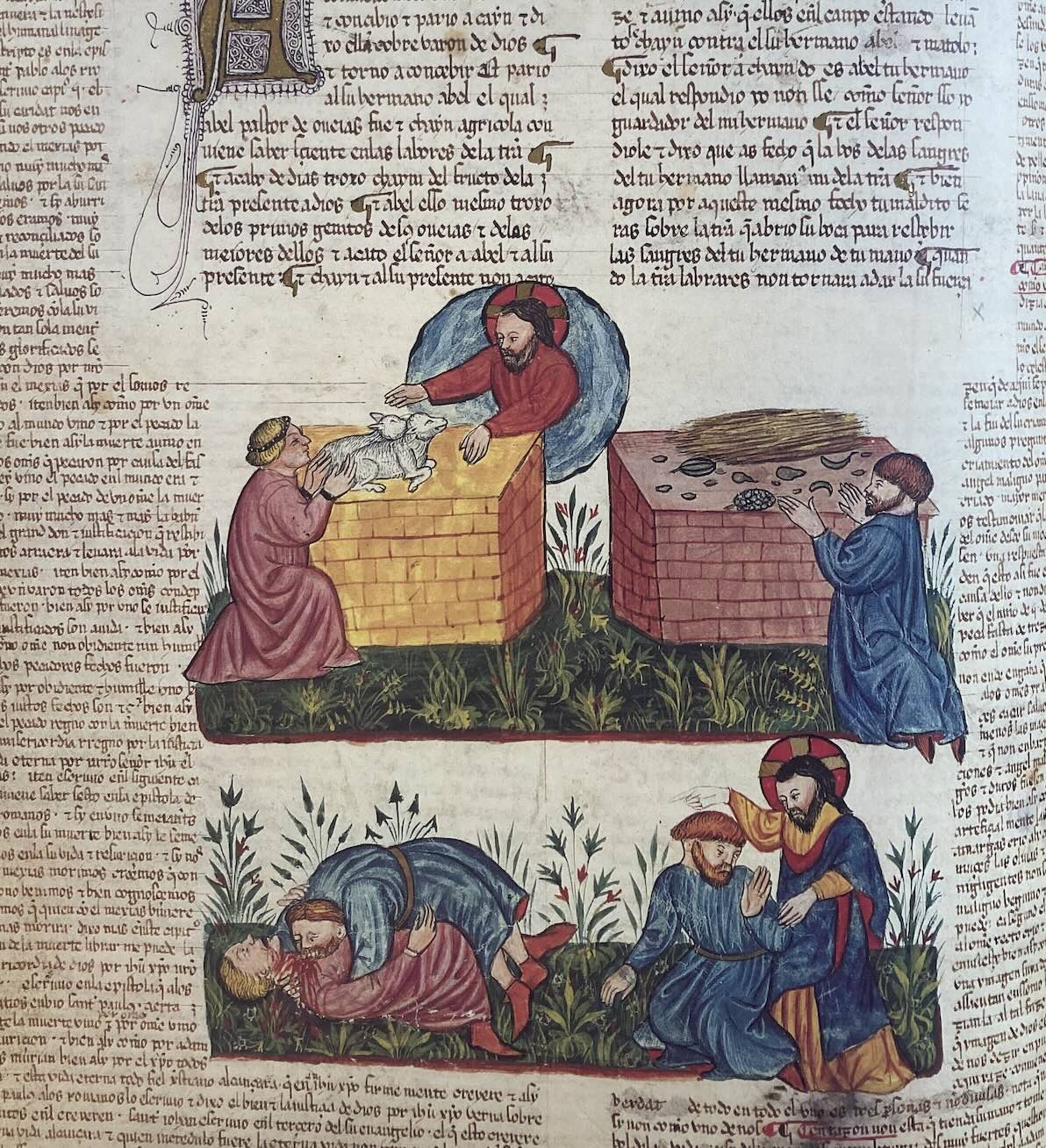

Figure 1: Cain and Abel (Alba Bible, fol. 29v)

Religious co-production may take many forms, arising from interactions that may be physical or purely imaginary, and processes of transference and adaption which may be candidly admitted or carefully concealed. The Alba Bible is comparatively rare in advertising itself as the result of a deliberate collaboration between members of different religious communities. It is a late-medieval Bible, translated into medieval Castilian for a Christian patron by a rabbi, working under the supervision of several Christian friars, and illustrated by a team of artists in Toledo. The result was a remarkable interreligious coproduction created during a period in which Jewish life in medieval Spain was particularly precarious. After many centuries of obscurity, the Bible has been embraced in recent decades as a symbol of the deep roots of Sephardi Jewish culture in Spain and as an example of tolerant interfaith collaboration. For all that, the story of its origins makes it an ambivalent emblem for the cooperation across the assymetries of power between religious majority and minority.

The Alba Bible: Symbol of Interfaith Collaboration

On Tuesday 31st of March 1992, Juan Carlos I of Spain and President Chaim Herzog of Israel met to commemorate and symbolically repeal the Alhambra Decree, which had expelled the Jews from Spain precisely five centuries earlier. In Madrid’s only synagogue they prayed together for peace and voiced hope that the dark history of Iberia’s Jewish-Christian relations was entering a new phase. That evening official ceremonies struck a more positive note: they visited the Pardo Palace to celebrate a symbol of tolerant cooperation between Jewish and Christian Spaniards of earlier times: a manuscript known as the Alba Bible.

The manuscript – named after its modern owners, the Ducal family of Alba – was created over the course of more than a decade by a rabbi, several friars, and a team of artists generally assumed to have been Christian. At its core is a Castilian translation of the Bible, made directly from the Hebrew by Rabbi Moses Arragel at Maqueda, slightly north-west Toledo, between 1422 and the early 1430s. The translation, copied out onto 515 folia, is surrounded by over six thousand glosses (also in Arragel’s Castilian translation), and illustrated by 325 miniatures, often displaying rabbinic details from the glosses, which were painted by at least two different ateliers in Toledo. Taken together, the glosses form a continuous commentary on the Bible compiled from a range of authorities, predominantly rabbinic, but occasionally also Christian – an early example being the gloss which announces the true Trinitarian sense of Genesis 1:26 (“Let us make man in our image”).

The result is a unique combination of Jewish and Christian perspectives on the Scriptures shared by both religions. Consider the illustration of Cain and Abel (figure 1): both registers depict God as Christ, with a red and gold quartered halo, accepting Abel’s offering in the upper left and banishing Cain in the lower right. But note the murder scene in the bottom left. Genesis 4:8 gives no details of how Cain killed Abel, leaving later generations to fill in the blank. Medieval illustrators improvised a variety of murder weapons, from axes and knives to clubs and sticks. Only one literary source has Cain use his teeth: the Zohar, a Cabbalistic text produced in late thirteenth-century Spain, has Cain bite Abel in the neck like a snake (Zohar 1:54b). And this is precisely what we find in the Alba Bible’s illustration of this episode: Cain closes his jaws on the lower part of Abel’s throat, covering both brothers in blood.

Still, what looks to the historian like a “Jewish” detail may not have seemed such to contemporaries, since this was not the first time that this mordent detail had made its way into Christian visual arts. In the exterior wall of Toledo Cathedral, which boasts 56 low-relief sculptures from the end of the 14th century, there is a scene which closely resembles that in the Alba Bible. Cain leans over Abel, pulling his head back by the hair, and plunging his teeth into his neck. Given that Arragel’s glosses make no mention of this Cainine behaviour, it seems likely that this originally Jewish detail reached the painters of the Alba Bible through their direct observation of local church sculpture – a striking illustration of how visual and conceptual motifs of medieval Spain could be co-produced across religious boundaries.

A Bible’s Genesis: Orchestrating a Co-Production in Troubled Times

Still, the Alba Bible’s miniatures teem with images and interpretations which are unambiguously identified as rabbinic by the commentary. This combination of self-consciously Jewish and Christian motifs may surprise, given that the previous three decades had seen a sharp rise in the persecution of Iberian Jews. In 1391 anti-Jewish sermons in Seville had escalated into a wave of violence that spread across Spain and reportedly saw some 200,000 Jews forcibly baptized. 1412 saw a series of anti-Jewish laws promulgated in Valladolid by Vincente Ferrer, which forced Jews into ghettos and required them to be recognizable by badges, rough clothing and long hair and beards. A year later came the Disputation of Tortosa, in which the Jewish participants were subjected to violence and intimidation, and precipitated another wave of Jewish conversions to Christianity. With the deaths of Vincente Ferrer and Ferdinand of Aragon, however, there came a change of tone: Ferdinand’s successor, Alfonso V, restored the rights, property, and books to the Jews of Castile in 1419. And it was just three years later that Rabbi Moses began his translation.

What interests and motives stood behind this unusual project? Almost everything we know about the manuscript’s genesis comes from its first 25 folia, which reproduce several crucial pieces of correspondence. The patron was Don Luis de Guzmán, Grand Master of the military Order of Calatrava and a major political actor in Castile. On the 5th of April 1422, Don Luis wrote to Moses Arragel, a resident of his lands, asking him to make a romance Bible translation directly from the Hebrew text, accompanied by a commentary which anthologized the most recent rabbinic scholarship.Don Luis was not the first to commission this type of work: a handful of other biblias romanceadas were created for Christians by Jewish scholars over the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, though their patrons and translators are mostly unknown. But the glosses and illustrations of the Alba Bible reveal greater ambitions. Christian scholars had long taken a keen interest in Rabbinic interpretations of Scripture, often with the aim of being better able to refute Jewish opinions and aid their conversion to Christianity. A valuable resource was Nicholas of Lyra’s Postillae, composed between 1322 and 1332, which contained Latin translations of a wide range of Jewish exegesis, often accompanied by illustrations. But by 1422 the Postillae was a century out of date, and it had come under criticism. The converso Pablo de Santa María, bishop of Burgos, complained of its over-reliance on Rashi to the neglect of other Jewish sources. Pablo wrote an extensive commentary on the Postillae which incorporated a mass of rabbinic material, which he knew well from his pre-Christian life as rabbi Solomon Halevi. The letters written to rabbi Moses by Don Luis and his associates suggest that their goal was to create an updated and fully integrated version of the Postillae: an illustrated Bible commentary with the most recent rabbinic opinions.

When Don Luis first approached Moses Arragel to propose the project, the rabbi respectfully declined. He gave several reasons, chief among them religious scruples. Arragel was, he said, unwilling to participate in a project which would involve depicting God and, from a Jewish perspective, thereby commit a sin:

By attributing to God a material form, we would be acting counter to all science and truth. [...] in my view, it is impossible to include depictions or images of Him without sinning against the law of my people. As for commissioning painters to do the work, since I know nothing of illumination, I would have to direct them in it, and that I could not do unless so instructed / forced [syn cargo].

R. Arragel (Alba Bible, fol. 9rb-9va, tr. S. Fellous-Rozenblat, adapted)

Don Luis was undeterred. He responded by reaffirming the commission, assuring the rabbi that he would not be required to participate in the production of the images, and offering the assistance of two of his own cousins, Don Vasco de Guzmán, Toledo’s Dominican archdeacon, and Arias de Ençinas, the Franciscan Superior of Toledo, who would also provide Arragel with Christian interpretations of the Bible for inclusion in the commentary. Two weeks later, after a strongly worded letter to Arragel from Brother Arias, it seems that the project had begun.

-kopie.jpg) Figure 2: The scholars at work (Alba Bible, fol. 1v): Rabbi Moses Arragel seated between Arias de Ençinas (Franciscan Superior of Toledo, right) and Don Vasco de Guzmán (Dominican archdeacon of Toledo, left)

Figure 2: The scholars at work (Alba Bible, fol. 1v): Rabbi Moses Arragel seated between Arias de Ençinas (Franciscan Superior of Toledo, right) and Don Vasco de Guzmán (Dominican archdeacon of Toledo, left)

The Bible’s artists also illustrated the interactions between Don Luis, Arragel, and the friars. Figure 2 shows the scholars in action, with Moses Arragel seated between his two Christian collaborators and supervisors, Brother Arias (right) and Don Vasco (left). Each of the three figures has both hands raised with a finger extended in instruction. Rabbi Moses, outnumbered two to one, cuts a diminuitive figure, represented at half the size of the Christian counerparts. Within an artistic tradition where size reflects status, the artist layed clear visual emphasis on the asymetries of power.

Co-Producing Scripture Across Asymmetries of Power

The ceremony in Madrid’s Pardo Palace, on the last night of March 1992, was organized to celebrate the completion of a facsimile edition of the Alba Bible, with a print run of 500 copies, one for each year since the Alhambra Decree. Juan Carlos and Chaim Herzog were both presented with a copy, each weighing in at 20kg. This time, the driving force behind the facsimile project was a Sephardi businessman, Mauricio Hatchwell Toledano (1940–2011), founder of the Fundación Amigos de Safarad, who had been born into Casablanca’s Jewish community before emigrating to Spain in 1964.

The Alba Bible holds an obvious appeal for those in search of positive examples of interfaith collaboration. To cite Arragel’s own words, it is a Bible which “leaves everyone free to believe, argue and defend his own law as much as he can” (fol. 15ra, a cada vno desy queda el creer, disputar e sostener su ley quanto mas podra, trans. M. Lazar). Arragel’s preface explains how his readers should approach the commentary’s unusual blend of Jewish and Christian views: Where there are no opposing views, Arragel says, his gloss should be acceptable to Jews and Christians. If he has accidentally neglected a difference between the two traditions, Christians should view the unfamiliar interpretation as a Jewish opinion, not a negation of their own faith; and Jews should do likewise. When there are fundamentally opposing views, these will be brought up in the opening part of the gloss and both positions explained. Arragel’s neutral, ecumenical and respectful tone inspired the scholar Moshe Lazar to describe this as “one of the most enlightened positions expressed in the medieval world”.

-kopie.jpeg) Figure 3: Rabbi Moses presents his Bible to Don Luis (Alba Bible, fol. 25v)

Figure 3: Rabbi Moses presents his Bible to Don Luis (Alba Bible, fol. 25v)

Yet, as a symbol of interreligious collaboration, the Alba Bible retains a deep ambivalence. Several years after the completion, rabbi Moses had still not been paid. We do not know whether he ever received the wage he had been promised for more than a decade of labour. It is also unclear how consensual his participation was in the first place. The correspondence at the start of the Bible meticulously documents the rabbi’s statement that he would not participate, and the letters which instructed him to proceed regardless. As a resident on the Grand Master’s lands, he was poorly placed to escape once his first refusal had been brushed aside. His reluctance may have also had other motives than those stated. He doubtless knew that the Christian drive to acquire Jewish learning was not always – or even typically – felt by those sympathetic or tolerant towards Jewish life in Spain. On the contrary, it was deeply embedded in the anti-Jewish practices of medieval Christianity. The expositions of rabbinic views by Nicholas of Lyra and Pablo of Burgos were important tools in the theological attacks on Judaism which were becoming increasingly common. Pablo of Burgos, alongside his supplementary commentary on the Postillae, was also the author of a number of polemical anti-Talmudic tracts. His student and fellow converso, Jerónimo de Santa Fe (formerly Joshua al-Lorqi), had been the initiator of the Disputation of Tortosa, less than a decade before Don Luis set his project in motion. The completion of the Alba Bible was also celebrated by a public disputation, at which Christian theologians, knights, Jews and Moors had the chance to express their opinions. We have no detailed record of the event, so we do not know whether Arragel participated (be it voluntarily or under compulsion), nor do we know whether the tone was one of respect, or a repetition of the humiliation visited on the Jews at Tortosa. But, to judge from the Bible itself, it seems likely that the strict hierarchies of religions would have been visible. The Bible’s paratexts relate how Dominican and Franciscan friars supervised and supplemented Arragel’s labours before finally subjecting them to official scrutiny. And, in a painting of the work’s official presentation, the rabbi offers his Bible to Don Luis (enthroned in figure 3). Kneeling, book in hand, Arragel is portrayed in accordance with the mandates of the Statues of Valladolid: with long hair and beard and red marks on his shoulders.

-kopie.jpg) Figure 4: Phineas’s zealous spearwork (Alba Bible, fol. 128r)

Figure 4: Phineas’s zealous spearwork (Alba Bible, fol. 128r)

It also seems probable that the terms of collaboration promised to rabbi Moses were not observed. Before the project began, Brother Arias had assuaged Arragel’s concerns about the anthropomorphic depiction of God by promising that he would have no part in creating the images. But there are clear signs that Arragel was involved in some way. Consider the depiction of Phineas’s “zealous” murder of Zimri and Cozbi, which I have discussed in another article. Of the episode’s two illustrations, the latter (figure 4) has a specifically rabbinic motif: Phineas hoists the fornicators aloft on his spear, aided by a string of miracles described in several rabbinic sources and paraphrased in the Alba Bible’s glosses. Arragel’s commentary is clearly in dialogue with the image produced by his Christian collaborators, since it makes explicit reference to the image (with the words “as you can see depicted”, segund que vees que esta figurado). This has led some to think that Arragel may also have been responsible for the introduction of Jewish motifs into many other miniatures, especially those which do not appear in the glosses.

The co-production of this Bible, as framed by its opening folia, unfolded within the highly unequal power relations of contemporary Castile. It is rightly celebrated as a unique example of interreligious co-production, through an unusually close collaboration between a Jewish rabbi and several Christian friars. But this collaboration took place on wholly Christian terms, and quite possibly despite the wishes of its Jewish collaborator.

Further Reading

Fellous-Rozenblat, Sonia. 1992. ‘The Biblia de Alba, its Patron, Author and Ideas’, in La Biblia de Alba: An Illustrated Manuscript Bible in Castilian. With Translation and Commentaries by Rabbi Moses Arragel. Commissioned in 1422 by Don Luis de Guzmán and now in the Library of the Palacio de Liria, Madrid. Madrid: Fundación Amigos de Sefarad, 2 vols. Vol. ii. (ed. Jeremy Schonfield) The Companion Volume, 49–64.

Fellous, Sonia. 2001. Histoire de la Bible de Moïse Arragel: Quand un rabbin interprète la Bible pour les chrétiens, Tolède, 1422-1433. Paris: Somogy.

Franco, A. 1987. ‘El Genesis y el Exodo en la cerca exterior de la catedral de Toledo’, Toletum 21: 53–160.

Lazar, Moshe. 1992. ‘Moses Arragel as Translator and Commentator’, in La Biblia de Alba: An Illustrated Manuscript Bible in Castilian. With Translation and Commentaries by Rabbi Moses Arragel. Commissioned in 1422 by Don Luis de Guzmán and now in the Library of the Palacio de Liria, Madrid. Madrid: Fundación Amigos de Sefarad, 2 vols. Vol. ii. (ed. Jeremy Schonfield) The Companion Volume, 157–200.

Nordström, Carl-Otto. 1967. The Duke of Alba's Castilian Bible: A Study of the Rabbinical Features of the Miniatures. Uppsala.

Online Resources

Facsimile Editions’ Webpage on their creation of the Alba Bible: https://facsimile-editions.com/ab/ (accessed 23.6.2025).

Ignacio Cembrero, El País May 31st 1992, ‘El Rey celebra en la sinagoga de Madrid “el encuentro con los judíos españoles”’ (https://elpais.com/diario/1992/04/01/espana/702079221_850215.html, accessed 23.6.2025).