Sarah Islam, 2023

The Cave of the Seven Sleepers in al-Rajib: A Co-Produced Christian-Muslim Site of Veneration

The Cave of the Seven Sleepers—who are often referred to in the Islamic tradition as aṣḥāb al-kahf, and in Christian sources as the “Sleepers of Ephesus”—is a holy site in the village of al-Rajib, Jordan. According to Islamic and Christian sources, several youth fleeing the religious persecution of the Roman emperor Decius sought shelter in this cave in the middle of the third century CE, emerging miraculously alive centuries later. Etched into the cave walls are inscriptions of Christian and Islamic symbols. For centuries Muslim and Christian scholars have debated the details and authenticity of the site. Despite disagreements among scholars of both traditions, Christian and Muslim believers have continued visiting the site for centuries, bringing their hopes for divine intercession and healing.

Christian and Islamic Narratives

The earliest recorded narratives are ascribed to Syriac bishop Jacob of Serugh (d. 521) who mentions a lost Greek text from the Levant as his original source. It was Bishop Gregory of Tours’ (d. 594) account, included in his Latin Glory of Martyrs, that would be widely disseminated across medieval Christendom. Later accounts abound, among them Paul the Deacon’s (d. 799) History of the Lombards, and the influential Golden Legend by the archbishop of Genoa, Jacobus de Voragine (d. 1266).

The narrative favored by most Christian authors is set during the religious persecutions of Roman emperor Decius in 250 CE. Accused of adhering to Christianity, several youths refuse to return to the pagan worship of Roman gods as demanded by Decius and hide in a cave to escape persecution, where they fell asleep. Over the next two centuries Christianity shifted from persecuted religion to the state religion of the Roman Empire. In 447 CE, during the reign of Theodosius II, theologians were engaged in intense debate over whether the physical body would be resurrected in the afterlife. It is in this period, some two centuries after the beginning of their sleep, that the youths awoke. Understandably hungry, they attempted to buy food, and the townspeople, astonished to see coins several centuries old, called upon the local bishop. After recounting their story, the Sleepers died in the cave. The incident was presented as evidence affirming resurrection in the afterlife.

Disagreement would arise about the details. Accounts from Christian communities in Najran mentioned three men, while Syriac Levantine accounts pointed to eight. Gregory of Tours recorded their slumber as lasting 373 years, while Jacobus de Voragine offered 196. The names in the account offered by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch Michael Syrus (d. 1199) differed from those in Gregory of Tours’. The Sleepers were sometimes considered saints. During the Crusades, what were believed to be their bones were transported from sepulchres near Ephesus, Turkey—one of many claimed sites of the original cave—to be preserved as relics in the Abbey of St. Victor. But their story was also sometimes discounted as apocryphal, for example by Caesar Baronius (d. 1607), Cardinal of the Latin Church.

According to Muslim exegetes, the Madinan Jews asked Muhammad about this story to ascertain the authenticity of his prophecy. As is often the case, the Qur’an refers to the story in generalities, in verses 18:7-18:26. It then provides a corrective to the Christian narrative, stating that many have debated about the incident’s details, but that these details are insignificant. What matters is the Sleepers’ commitment to monotheism in the face of oppression, and God’s ability to demonstrate the truth of resurrection. Like Christian scholars, Muslim scholars attempted to locate the narrative historically and geographically. Al-Ṭabarī (d. 923) and al-Wāqidī (d. 823), for example, pointed to the location in modern Jordan, while others would point to locations in Turkey.

The Cave in al-Rajib as a Site of Veneration

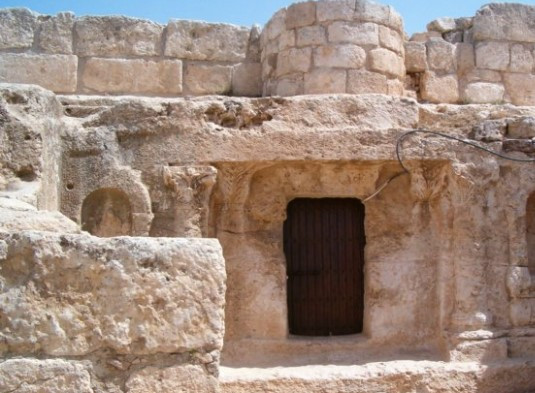

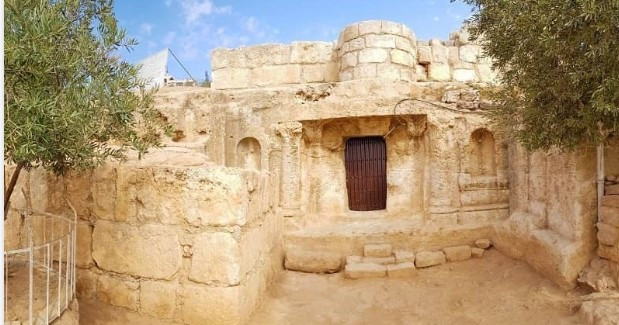

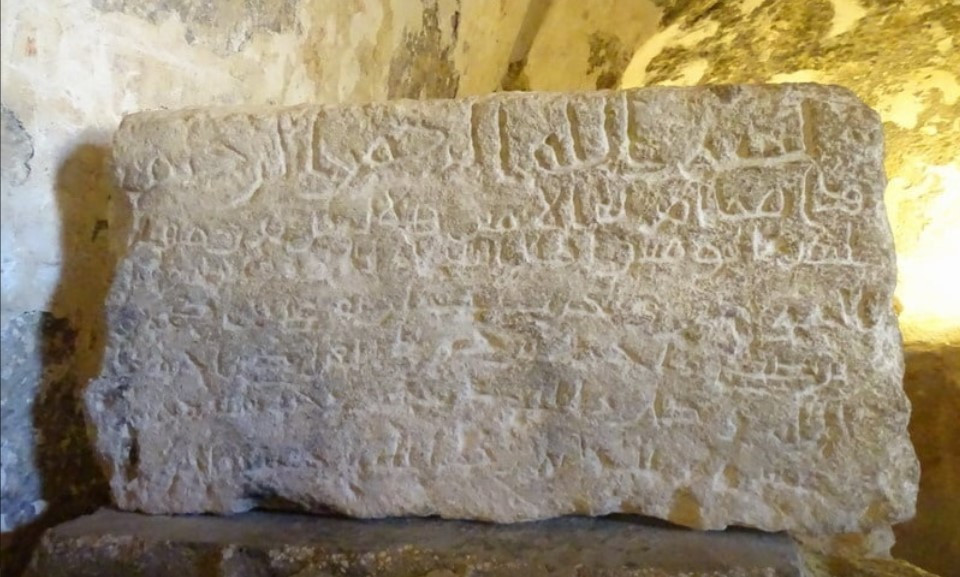

The cave in al-Rajib is flanked by remains of two mosques and a Byzantine cemetery. Two square stone pilasters and adorned niches from the remains of a Byzantine church line the cave’s entrance. An eroded mosque miḥrāb is embedded in the cave’s southern wall. Nearby are the foundations of a minaret, four Byzantine pillars fifteen feet apart, and an Arabic inscription stating that this (second) mosque was built by the son of Aḥmad ibn Ṭulūn (d. 884). Archeologists note that this structure was likely a Byzantine church converted into a mosque during the Umayyad caliphate of ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (d. 705), and later renovated under the Ṭulūnid dynasty.

The cave entrance points south, aligned with the miḥrāb and Qibla. Inside the cave sit seven stone sarcophagi. Inscribed on one is the Byzantine Christian octagon. Next to it, a large hole is carved out, now covered with glass, through which visitors can see the bones of the buried. Inscribed on the wall on the left are the basmala along with Qur’anic verses in Kufic script.

Muslim visitors cite reports from Ibn ʿAbbās, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad, which state that the Sleepers were so beloved to God, that invoking their names to remember God’s mercy provides relief from ailment. Christian visitors note the virtue of visiting the relics to alleviate illness. The co-produced mixed symbology from the site’s Byzantine and Islamic history is unsurprising. What is surprising is that believers of both faiths still actively use the site. Islamic burial practices prohibit the veneration of relics. One might expect Christians to be deterred by the presence of Qur’anic inscriptions. Yet, despite theological disagreements between scholars of both traditions, the cave continues to be a site into which every year thousands of Muslim and Christian visitors pour their hopes for divine intercession. In the shared veneration of these saints and in the ritual act of visiting their tombs with hopes of healing, we find the co-production of a shared set of religious objects, habits, ideas, and yearnings between Muslims and Christians spanning several centuries.

Further Reading

The Madain Project Jordan Archeological Archive, “Cave of the Seven Sleepers,” accessed March 25, 2023, https://madainproject.com/cave_of_the_seven_sleepers.

Muḥamamd ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 923), Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl āy al-Qurʾān, ed. Maḥmūd Shākir (Makka: Dār al-Turāth, 2010), 17:591-626.

Sebastian Brock, “Jacob of Serugh’s Poem on the Sleepers of Ephesus,” in ‘I Sowed Fruits into Hearts’ (Odes Sol. 17:13), Festschrift for Michael Lattke, ed. P. Allen, M. Franzmann, and R. Streelan (Early Christian Studies 12; 2007), 13-30.

Sidney Griffith, “Christian Lore and the Arabic Qu’ran: the ‘Companions of the Cave’ in Surat al-Kahf and in Syriac Tradition,” in The Quʾran and its historical context, ed. G.S. Reynolds (2008), 109-37.

(photo credits: Sarah Islam)