Yonatan Binyam, 2024

The Kitab al-Aghānī and the Sahaba in Christian Ethiopia

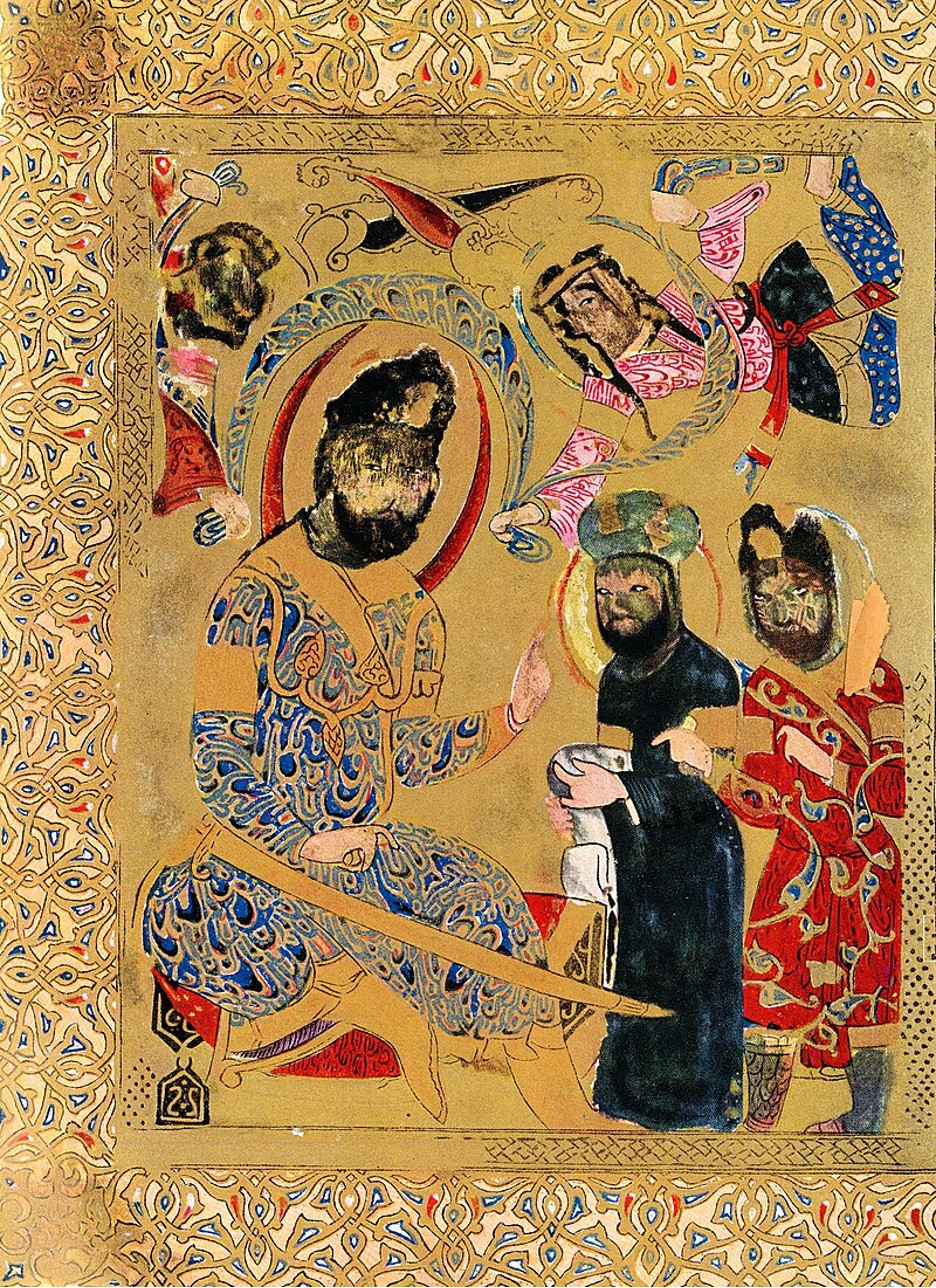

Illustrated manuscript of the Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218–1219. Vol XI. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579, depicting an enlarged, seated figure with two flying genii holding a canopy over his head as he is approached by two men. This scene is interpreted by some as a depiction of Muhammad conducting a treaty with representatives from the Christian city-state of Najran.

According to Islamic tradition, the earliest followers of Muhammad constituted a minority group that became increasingly oppressed as it grew in number. The tribes inside Mecca, most notably the Quraysh, felt more and more threatened by the rising influence of the man they had initially dismissed as a deluded teacher. The Quraysh responded to the growing influence of Muhammad by persecuting his small but rapidly expanding community.

Some sources in this tradition, like the Kitāb al-maghāzī of Ma’mar ibn Rashid (d. 153 AH/770 CE), relate that during this critical moment in the nascent stages of the movement (c. 615–616 CE), Muhammad sent a group of his followers across the Red Sea to seek refuge in the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia, or Abyssinia. This group of Muhammad’s first followers, known as the sahaba, journeyed to Ethiopia in order to plead their case before the king, or al-najashi, as he is referred to in Muslim sources. In some versions of the story, the king is identified as a certain Ashama, although no historical evidence survives to corroborate the existence of such a figure.

Whether real or fictionalized, this story of first contact between Muslims and Christians contains a fascinating example of co-production, wherein the author of the narrative emphasizes the religious kinship between Christianity and the teachings of Muhammad. The story (or akhbār) is told in a number of Muslim sources, from the sīra of the Prophet to history books to collections of hadīth. Arguably the most popular version of the story is recounted in the Kitab al-Aghānī, or The Book of Songs, a collection of poems and stories that ranges from pre-Islamic times until the end of the ninth century CE.

According to the Kitab al-Aghānī, when the sahaba went to Abyssinia and took refuge there, the Quraysh sent two of their members to bring them back to Mecca by bribing the Ethiopian king to release them. The text then relates that when one of the sahaba (a man named Ja‘far ibn abī Tālib, who happened to be Muhammad’s cousin) was summoned before the king, he pleaded the case of his community by reciting a short catechism and a passage from Surat Maryam. In response, the king wept until his beard was soaked with tears. In a rare moment of a Christian making inclusive and affirmative statements about Muhammad’s teachings, he declared that the beliefs relayed to him by Ja‘far had come from the same source as those taught by Jesus in the Gospel. The king’s response serves to encapsulate the story’s central message: a Christian monarch was receptive to Muhammad’s earliest followers because he recognized that the Prophet’s teachings stemmed from the same prophetic tradition as Christianity.

The Kitab al-Aghānī also contains another story that parallels the first account of the Christian king’s response to the teachings of Muhammad. It relates how the Qurayshites again sought to incite the king’s anger against the sahaba by informing him that they believed Jesus to be a mere human being, and not divine. When brought before the king a second time to explain their beliefs, Ja‘far proclaimed the teachings of the Prophet concerning the central figure in Christianity: Jesus was the servant, apostle, spirit, and word of God who was brought forth from the virgin Mary. The king responded by utilizing the length of a small piece of wood (‘uwayd) to symbolize the minuteness of the gap between Ja‘far’s statements about Jesus and what Christians believed. He then expelled the members of the Quraysh tribe back to Mecca, refusing to give up the sahaba taking refuge in his kingdom.

These episodes are only two of several stories early Muslims told about the Christian king of Abyssinia who protected the first followers of Muhammad from their enemies in Mecca. In another version of the story, the king is said to have recited the shahada before he died, and it is told that when news of this reached the Prophet, Muhammad performed the salāt for him. In this way, the najashi himself becomes a co-produced figure in these narratives, one who blurs the line between Christian and Muslim. While it is impossible to verify these accounts of Ashama and what is sometimes called the First Hijra, they nonetheless serve to demonstrate repeated efforts in the earliest Muslim communities to emphasize the point that Christianity and Islam are rooted in the same prophetic tradition.

Further Reading:

Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī. Kitab al-Aghānī. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub Press, 1927.

Shavit, Uriya. “Europe, the New Abyssinia: On the Role of the First Hijra in the Fiqh al-

Aqalliyyāt al-Muslima Discourse.” Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 29, no. 3 (2018): 371–91.

Erlich, Haggai. Islam and Christianity in the Horn of Africa: Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan. Boulder,

CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2010.

Erlich, Haggai. Ethiopia and the Middle East. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1994.

Raven, Wim. “Some Early Islamic Texts on the Negus of Abyssinia.” Journal of Semitic Studies

33, no. 2 (1988): 197–218.

Rice, D. S. “The Aghānī Miniatures and Religious Painting in Islam.” The Burlington Magazine

95, no. 601 (1953): 128–35.