David Gyllenhaal, 2023

A Syrian Christian Rite for the Baptism of Muslim Children

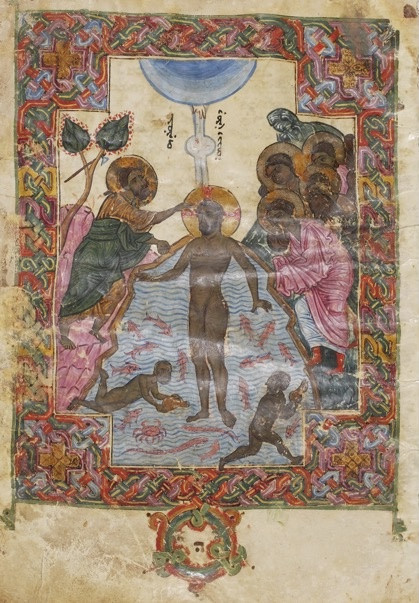

Church of the Forty Martyrs MS 41, f. 37r.

In 1153 Mor Yoḥannan, the Syrian Orthodox bishop of Dara and Mardin in medieval Anatolia (modern Turkey) was confronted with a problem: Muslim parents were having their children baptized. What Christian bishop could possibly object to a Muslim child becoming Christian? The problem was that after these children were baptized, their parents continued to raise them as Muslims. From the perspective of all formal theologies of the Christian East, this was a contradiction in terms; baptism was meant to mark the receiver's profession of belief in Christ and initiation into the community of the faithful. But the parents of these children apparently did not see things this way. They wanted their children to be baptized—but stay Muslim. This was a peculiar conundrum, and the bishop asked a church synod to resolve it. The synod's surprising solution: a distinct baptismal rite created for these Muslim children (Vööbus, p. 246). The baptism was modelled on that of John the Baptist rather than Christ, promising remission of sins rather than converting the child to Christianity. In this way the synod met the ritual needs of these parents while maintaining the distinction between Christian and Muslim. Through the eccentric window of this unusual canon, we can see Muslim and Christian communities coproducing their mutually exclusive realities by wrestling with the consequences of their own profound entanglement with one another.

The full extent of that entanglement becomes even clearer if we ask why these parents wanted their children baptized in the first place. For centuries under the rule of the East Roman empire Anatolia had been largely Christian, but the Turkish conquests of the 11th century resulted in a gradual trend towards conversion to Islam (see Vryonis). The earliest reports of Muslim baptism point explicitly to the mixed religious situation of Anatolia as cause. The 12th century Greek Orthodox canon lawyer Theodore Balsamon described the scandal caused in a church synod in Constantinople by the revelation that Muslims in the eastern provinces sometimes sought baptism for their children, "supposing that their children will be demon-possessed and smell like dogs if they do not obtain Christian baptism" (Rhalles and Potles p. 498). According to Balsamon, the baptized children had Christian mothers who insisted on the rite, raising the topic of intermarriage. We should not assume that all Muslim baptism was done at the initiative of Christian mothers, but Balsamon’s description does suggest a region in which Christians and Muslims were intimate. Whether these parents thought baptism would defend the child from demon possession or bad odor—as the polemical text of Balsamon claims—we can never know for sure. But in a premodern landscape where literacy and formal religious education were rare (on which see Tannous), perhaps they saw baptism not as an act of conversion so much as an additional spiritual investment in the health and future prospects of their child.

The synod of Mor Yoḥannan took a more generous approach toward this practice than the bishops in Constantinople. Confronted with the ongoing reality of Muslims showing up for baptism, the synod's 25th canon decreed a distinct baptismal ceremony carried out separately from the baptism of Christian children:

Canon 25. However, regarding the children of the Muslims we issue instructions with caution, and we tell you, by apostolic commandment, that the priests are not allowed by God to baptize them together with the children of the believers in our holy font. But there shall be another baptism for them, apart, on another day, whether before or after, with plain water... And let the priest baptize the children of the Muslims, as he, the priest, says thus: "This N.N. is baptized in the name of the Lord in this baptism of John for the remission of debts and for the forgiveness of sins. Amen." And they shall anoint him with plain oil. (trans. Taylor, p. 444).

The solution is ingenious. The New Testament makes an explicit contrast between the baptisms done by John the Baptist "with water for repentance" and Christ's baptism "with the Holy Spirit and fire." (Matt. 3:11 NIV). By changing the verbal formula, and by substituting "plain oil" in place of the specially consecrated chrism reserved for Christian baptism, the synod relocates the baptism of the Muslim child into an earlier dispensation of salvation history. As is so often the case with religious co-production, a text meant to produce a clearer distinction between Christian and Muslim reveals just how intimately entangled those communities really were.

Further Reading

Arthur Vööbus, The Synodicon in the West Syrian Tradition II, CSCO 375 (Louvain, 1976), p. 246.

Speros Vryonis, The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century (Berkeley, 1971).

Georgios A. Rhalles and Michael Potles, Σύνταγμα τῶν θείων καὶ ἱερῶν κανόνων, vol. 2 (Athens, 1852), p. 498.

Jack Tannous, The Making of the Medieval Middle East: Religion, Society, and Simple Believers (Princeton, 2018).

David Taylor, "The Syriac Baptism of St John: A Christian Ritual of Protection for Muslim Children," in The Late Antique World of Early Islam: Muslims among Christians and Jews in the East Mediterranean, ed. Robert G. Hoyland (Princeton, 2015), pp. 437-460.