Asceticism during Late Antiquity as a Case Study of Religious Co-production between Judaism, Christianity and Islam

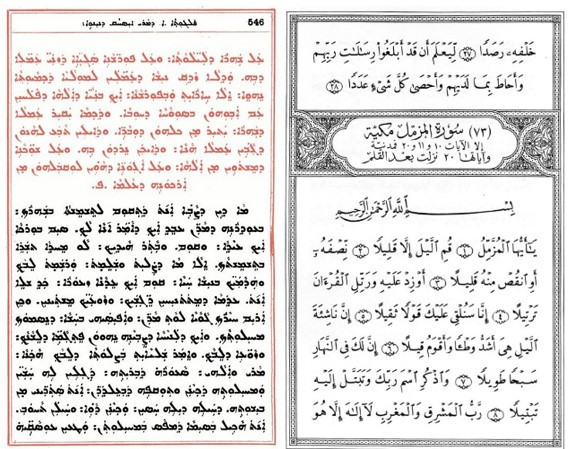

Syriac text: Isaac of Nineveh, Mar Isaacus Ninivita. De Perfectione Religiosa (ed. Paul Bedjan, Paris and Leipzig, Otto Harrassowitz, 1909) p. 546: chapter 80 'On vigils'. - Arabic text: page from a printed Qur'an (scan of the official Egyptian edition of the Qur'an, Cairo, 1924, p. 773 - source: https://corpuscoranicum.de/en/verse-navigator/sura/73/verse/1/print), surah 73 al-Muzzammil, verses 1-9.

I am excited to join the “Interactive Histories, Co-Produced Communities: Judaism, Christianity and Islam” project as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Bern. My contribution to this project is provisionally entitled “Asceticism during Late Antiquity as a case study of religious co-production between Judaism, Christianity and Islam” and aims at exploring the ways in which ascetical practices and beliefs in Judaism and Christianity during the Late antique period shaped the new religion we will come to know as Islam.

By and large, the Qur’anic text is one of parenetical nature as it constantly exhorts its listener and/or reader to think of and fear God and Judgment Day. The goal of this rhetoric is to bring the believer to radically change his or her behavior and to develop a new form of ascetical piety. Thus, the Qur’an insists on the following three actions that the believer must undertake to escape the torments of the afterlife: fear God and Judgment, pray constantly, and give alms. These acts, which involve self-denial and renunciation, are the ones most commonly associated with asceticism, and are also profoundly influenced by a form of piety which finds its roots in Eastern Christian monachism, as Swedish scholar Tor Andrae had noted a century ago. I therefore intend to compare either whole surahs or individual Qur’anic words, expressions, and concepts to a corpus of Christian Syriac texts ranging from John the Solitary’s (4th–5th century CE) ascetical treatises to John of Dalyatha’s (d. ca. 780 CE) ascetical letters and homilies. I will also address the question of what a collection such as the Jewish Babylonian Talmud (5th–6th or 6th–8th century CE) has to offer by way of comparison with Qur’anic ascetical discourses.

These precise comparisons will lead me to question the ways in which the Qur’an transforms and adapts previous religious traditions and the reasons it does so; they will also show that the cultural milieu in which the Qur’an took shape was one of active co-production between neighboring faiths which borrowed from each other, transforming various elements to make them their own, and creating a singular identity for themselves.

Other aspects of asceticism that are less often evoked when discussing this subject will also be properly examined. These have a close relation with the original meaning of the Greek askēsis in the sense of “exercise” and “training” (both mental and physical), and include on the one hand the question of the relation between violence and asceticism, notably through the concept of jihād (or “combat”), which involves a commitment to hard physical discipline, to enduring deprivation, etc., and on the other hand the related and crucial question of the “separation/exile” (hijra) of Believers from “unbelievers” or “associators” in the Qur’an — an emigration undertaken mainly out of need and desire, and which involves a secessionist dimension with the desire to eradicate one’s past life. This secession points to the formation of a religious identity in relation, or rather in opposition, to an (sometimes imagined) other.