Shlomo Zuckier, David Gyllenhaal , 2024

In Search of a Sinful Pun: The Coproduction of Israelite Sin in the Qurʾan and Early Islamic Exegesis

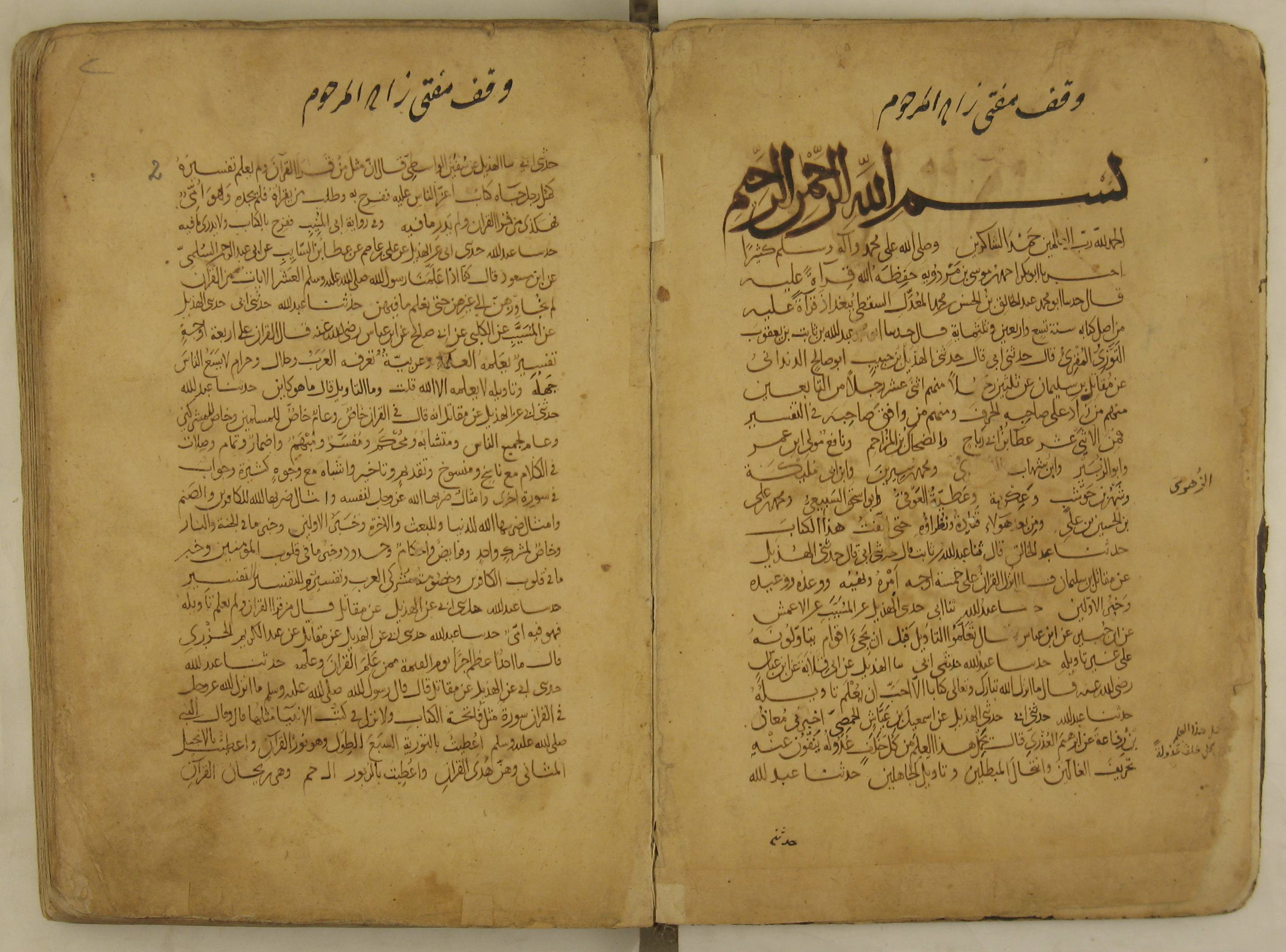

A manuscript of Muqatil ibn Sulayman's Tafsīr copied in the Sultanate of Rum, modern Turkey, in 1233 CE.

One important implication of the entangled scriptural heritage of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam is that members of one faith may find it useful to consult the traditions of another faith about their own scripture. While Muslims do not accept the Torah as scripture, many stories in the Qurʾan are based on and refer to stories and teachings of the Hebrew Bible, such that biblical materials may be helpful in Qurʾanic exegesis. Here we examine an interesting case study of this phenomenon, in which an early Muslim exegete, Muqatil ibn Sulayman (d. 767 CE) draws on the Hebrew Bible and Jewish tradition to interpret a puzzling Qurʾanic passage about a sin the Israelites committed.

We begin with Qurʾan chapter 2 verses 58 and 59, which recount this mysterious sinful episode in Israelite history from God’s perspective:

And when We said, ‘Enter this township, and eat easefully of it wherever you will, and enter in at the gate, prostrating, and say, Unburdening (ḥiṭṭa); We will forgive you your transgressions, and increase the good-doers’ (58).

Then the evildoers substituted a saying other than that which had been said to them; so We sent down upon the evildoers wrath out of heaven for their ungodliness (59) (trans. A. J. Arberry).

Two questions about these verses present themselves. First, what is the real meaning of ḥiṭṭa, the word that God commands the Israelites to say? In Arabic, this appears to be a verbal noun that means “unburdening,” but that word does not make much sense in context. Second, what was the “saying” with which the Israelites replaced the word they were ordered to say?

The natural place to look for answers to these questions is the Arab-Islamic tradition of Qurʾanic interpretation, or tafsīr. Let us begin by posing our questions to the great tenth century exegete al-Tabari (d. 923 CE). First: what does ḥiṭṭa actually mean in this context? Al-Tabari tells us that no one really knows: “The exegetes are at variance about the exegesis of ḥiṭṭa.” He cites many different traditions—all wildly contradictory. Second: what word did the Israelites replace it with? Al-Tabari’s testimony is even more confusing on this point. He cites fourteen different traditions about the word with which the Israelites replaced ḥiṭṭa; almost all of them involve a confusing Arabic pun on ḥiṭṭa with words for grain, either with ḥinṭa (a word for wheat) or with ḥibba (a word for a single grain of wheat). Given these contradictory and confusing traditions, we still do not understand what ḥiṭṭa really means in these verses, nor do we know what word the Israelites were punished for putting in its place. Instead, we have stumbled into two further puzzles presented by the classical tafsīr tradition of Qurʾanic interpretation. First, God seems to demand a speech act from the Israelites (i.e., by pronouncing a particular word, their sins will be resolved); yet the Arabic word ḥiṭṭa does not seem able to serve as a speech act, giving rise to a confusing welter of contradictory interpretations among later Islamic exegetes. Second, most of these same exegetes seem to agree that the unspecified word which the Israelites substituted for ḥiṭṭa is a pun on a word for grain—but why?

For this question, we will turn to a much earlier work of tafsīr, written by Muqatil ibn Sulayman. By the time that al-Tabari was writing, nearly two hundred years later, Muqatil had an ambivalent reputation among Muslim scholars. Some parts of the Islamic scholarly tradition would eventually malign him for relying too much on knowledge of Jewish and Christian origin in his interpretation of the Qurʾan, and indeed modern scholarship has shown that he paraphrases rabbinic literature on occasion. Here is his key passage on these verses:

[Some of the Israelites] said: ‘hiṭā siqmāthā’—meaning red wheat [ḥinṭa ḥamrāʾ]. They said this as a ridicule and a substitution in place of what they had been ordered... God annihilated from among them 70,000 on one day as a punishment for their saying ‘hiṭā siqmāthā,’ so this saying was their wrongdoing.

By glossing it with an Arabic translation, Muqatil makes it clear that he believes hiṭā siqmāthā—the wicked replacement for the word ḥiṭṭa—is not Arabic. This points us towards a solution for the second question that emerged from our look at al-Tabari’s tafsīr: maybe the grain-related pun which later exegetes continued to repeat, but struggled to understand, makes better sense in a non-Arabic language. In fact, if we follow that suspicion, we also find Muqatil pointing towards a solution to the first question we had for the later works of tafsīr: how can we derive a speech act from the recitation of ḥiṭṭa? Muqatil is pointing us towards a grain-related pun, in a non-Arabic language, by which the Israelites evaded what God had really demanded of them: a formal confession of guilt.

When we look at Muqatil’s full exegesis of Qurʾan chapter 2 verses 58 and 59, we see him alluding to a variety of passages in the Hebrew Bible. Muqatil links his exegesis of this passage with the character of Joshua and the city of Jericho, which the Israelites entered after Moses had died and they entered the land.

In the biblical account, immediately following the capture of Jericho, one person named Akhan takes prohibited spoils from Jericho. After a subsequent loss in battle, the Lord tells Joshua that “Israel has sinned” (ḥata yisrael; Josh. 7:11), with one person’s sin attributed to all of Israel. Joshua undertakes a sort of lottery process to determine the culprit, which lands on Akhan, who then confesses to God (Josh. 7:19), saying “I have sinned (anokhi ḥatati) against the Lord, God of Israel” (Josh. 7:20). He is subsequently stoned and burned to death, along with his family, on God’s order. Another biblical text that Muqatil alludes to is Numbers chapter 14, which follows the negative report from the spies and the Israelites’ resultant unwillingness to enter the land, in response to which God declares that this generation will not enter the promised land (Num 14:22–23, 28–30,35). In response, a group, overcompensating for their prior unwillingness to enter, asserts “here we are, and we shall ascend to the place that the Lord says, for we have sinned (ki ḥatanu).” Moses tells them not to do so, because it defies the Lord; they ascend nonetheless and are killed. Muqatil’s account specifies the oddly particular detail that the Qurʾan’s divine punishment for saying the wrong thing “annihilate[d] from among them 70,000 on one day.” This particular detail is strikingly similar to what appears at 2 Samuel 24, where David, after imposing an improper census and admitting he sinned (ḥatati; 2 Sam 24:10,17), is offered a choice between three options of punishment by the prophet Gad: a seven-year famine, three-month military defeat, or a three-day plague (2 Sam 24.13). David chooses the plague, and thus Israel is struck with a plague taking place “from the morning until the fixed time,” in which 70,000 men die (2 Sam 24:15).

Muqatil seems to understand that the recitation of the term ḥiṭṭa is meant to yield forgiveness: it is a speech act yielding atonement. This mechanism of confession, a concept with deep biblical roots, generally involves stating the root ח.ט.א (ḥ.t.a, “to sin”) in first person. Applied to the Qurʾanic passage, the Israelites are asked to confess, fail to follow those instructions by saying something else instead of “ḥiṭṭa”, and are punished with death. On this interpretation, the word ḥiṭṭa as presented by the Qurʾan and Muqatil should be understood as a transliteration of a Hebrew or Aramaic word for sin (ḥ.t.a). Moreover, in each of the three biblical passages alluded to, a person or a group is expected to confess for a sin they committed, they fail to properly do so, and are killed as a result. This is precisely the fact pattern in this Quran passage as told by Muqatil – the Israelites sin, seem to confess, but it is apparently unsuccessful and they and are killed nevertheless.

We have thus solved our first puzzle. How is ḥitta a relevant speech act? It is a prescribed confession, based on the Aramaic or Hebrew words for sin. The second puzzle remains to be resolved: what is the pun about grain? Muqatil asserts that instead of the people saying ‘ḥiṭṭa’ as a confession for their sins, they swapped in the words ‘hiṭā siqmāthā’, a foreign word meaning red wheat. Indeed, the term ‘ḥiṭā siqmāthā’ is a perfectly intelligible transliteration of an Aramaic or perhaps Hebrew phrase meaning ‘red wheat.’ Muqatil points towards a scenario in which the Israelites presented themselves as if they were confessing by appearing to state ḥiṭṭa, “sin,” while they were actually saying ḥiṭā, “wheat.” Notably, the punning of wheat and sin appears in a Jewish passage produced not long before the Quran, as the Babylonian Talmud offers a pun between a grain of wheat (ḥittah) and sin (ḥattat) at Berakhot 61a. This pun is not new, but has been grist for the mill of Semitic-language religious interpretation for generations.

With this revelation, we can circle back to the questions proposed earlier: why would God ask the Israelites to say ḥiṭṭa, and what word did they substitute in its place? The theory of a sinful Aramaic or Hebrew pun on the words for “sin” and “grain” provides a satisfying answer to both questions: God asked the Israelites to confess their sin, but they disobeyed by way of a punning substitution, subtly twisting the word for “sin” into the nearly homophonous word for “grain.” The pun, just like the punishment, can be clarified by recourse to Jewish tradition, as the punning of sin and wheat appears in Hebrew and likely resembles Muqatil’s word play. While it is impossible to prove with certainty that this sinful pun lies behind the Qurʾanic passage itself, it represents a compelling solution, and one which could only have come from Jewish tradition. From the granular – and grammatical – analysis of red wheat to the accounts of puns and punishments across Jewish and Islamic tradition, only the Jews can help Muqatil explain an anti-Jewish passage in the Qur’an.

Bibliography

Arberry, A. J., trans. (1955), The Koran Interpreted, New York: Macmillan.

Gyllenhaal, David and Zuckier, Shlomo (forthcoming), “In Search of a Sinful Pun: A Granular Analysis of Q. 2.58–59,” Der Islam.

Mazuz, Haggai (2016), “Possible Midrashic Sources in Muqātil b. Sulaymān's Tafsīr,” Journal of Semitic Studies 61:2, 497–505.

Muqātil b. Sulaymān, Abū-l Ḥassan al-Balkhī, (1979-1989), Tafsīr, edited by ʿAbd Allah Maḥmūd Shiḥātah, 5 vols., Cairo: al-Hayʾa al-miṣrīya al-ʿāmma li-l-kitāb.

Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2018), The Qurʾān and the Bible: Text and Commentary, New Haven: Yale University Press, (esp. p. 48).

Rubin, Uri (1999), Between Bible and Qurʾān: The Israelites and the Islamic Self-Image, Princeton: The Darwin Press, (pp. 83–98).

al-Ṭabarī, Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr (2003), Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl āy al-quʾrān, edited by ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAbd al-Muḥsin al-Turkī, 26 vols., Riyad: Dār ʿālam al-kutub li-l-ṭibāʿa wa-l-nashr wa-l-tawzīʿ.

Witztum, Joseph (2022), “‘We Will Not Endure One Sort of Food’ (Q 2:61),” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 172, 135–148.