Shlomo Zuckier , 2022

Peacemaking as Muslim-Jewish Co-Production Under God: The (A)political Theology of Rabbi Menachem Froman

How do various religious groups from Late Antiquity to the Medieval period conceptualize divine will and how do those notions change once these groups begin using explicitly philosophical reasoning? As I reflect over the course of this year on how ideas often moved across faith lines despite the enmity that existed at times between the religious groups, I find it helpful of think of a near-contemporary religious figure who both prescribed and performed this mode of engagement across difference. This essay presents the (a)political theology of Rabbi Menachem Froman, whose approach to peacemaking I find deeply thought-provoking and worthy of study in its own right. It depicts a devout Jew who emphasized what he held in common with his religious Muslim neighbors, and who often adopted their language and embrace of their love of the Land alongside his own. This case study opens new directions in thinking about how religious communities interact and think together. For my particular research interests, the proposition that emphasizing God and not denomination as ultimate authority allows for greater sense of shared purpose with religious counterparts is a shared feature of Rabbi Froman’s thought and Jewish-Christian-Muslim medieval scholasticism.

Who Was Rabbi Menachem Froman?

Rabbi Menachem Froman was a man of seeming contradictions – a settler who worked towards peace and a mystical thinker who was profoundly embedded in this-worldly pursuits. He held a deep, enduring and exclusive connection to the Holy Land and simultaneously found the capacity to share that ideology with other religious groups.

Menachem Froman was born in 1945 in the Galilee and fought as a paratrooper in the Six Day War of 1967. He joined the Religious Zionist movement, studying at the Merkaz HaRav yeshiva and earning rabbinic ordination. He taught at a variety of Yeshivot and served as the rabbi of the Migdal Oz and Tekoa communities in Gush Etzion of the West Bank. A founder of the Gush Emunim movement committed to Jewish settlement of the Greater State of Israel, he was also close to many left-wing personalities in Israel. Starting in 1987 and until his death in 2013 he pursued an agenda of interfaith engagement while attempting to make peace through the settlements.

In a standard narrative regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, religion and Jewish settlements prevent peace. By contrast, Froman argued that peace can only be achieved through religion and, in fact, through the settlements themselves. In his view, rather than being obstacles, settlements had the potential to serve as models of co-existence between Israelis Jews and Palestinian Muslims living in the same area. He even referred to the settlements as “the fingers of Israel’s outstretched hand in peace.”

Fig. 1: Rabbi Menachem Froman celebrating the Lag Ba-Omer holiday in Meron, May 2012 — Source

Fig. 1: Rabbi Menachem Froman celebrating the Lag Ba-Omer holiday in Meron, May 2012 — Source

Common Religious Ground

Froman sought to reverse the standard way of evaluating the dual, Jewish and Muslim claims to the Land. What many understand as two competing contentions yielding a zero-sum game – does the land “between the river and the sea” belong to Jews or the Palestinians? – he presented as two identical claims: everyone in both groups believes that God made this land holy and wants them to live in it. He believed that with empathy, the ability to see the world from the Other’s perspective, the common goal of both parties could be perceived. The parties could then get past the hubristic possessiveness of wanting to not only live in the Land but to control the Land, making possible creative arrangements that could work for all.

Froman was open to a range of political solutions as to how precisely sovereignty could be divided, as long as all Muslims and Jews could stay in their homes in the Holy Land with a sense of dignity and safety. He was open to some version of a confederation arrangement, where Jews and Palestinians could each have their own state, with overlapping territories spread throughout the Holy Land. This arrangement – an alternative to the Two State solution that has been mainstream for over three decades – is today having a moment among certain policy thinkers. Froman’s approach effectively asked if there were a way to produce coexistence by learning how to live together rather than by seeking separation. He wondered if the way to bridge the cultural gap might be through the religious “extremists” rather than the secular “moderates,” not by sacrificing religious claims to the Land but finding creative ways to accommodate all such claims. A peace is only as strong as the restraint of its most extreme link; if extremists must be part of the solution, his approach suggested, it might make sense to start by finding common ground between the most radically religious groups on both sides.

In terms of its conceptual structure, Froman’s model was more bottom-up than top-down, built on the contention that peace is made primarily between people, not between governments. A theological student of Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav (1772-1810), Froman was both highly individualistic and skeptical of pride in all forms. On this view, government, often reliant on nationalistic pride, has the capacity to obscure the interpersonal bonds between peoples of different origins. The best path forward would be to emphasize something that Jews and Muslims hold in common – belief in the monotheistic God of Abraham who made the Land holy and granted it to Abraham’s descendants. Froman believed that privileging God and religion over political collective was a fundamental conceptual step towards resolving the conflict.

This was represented in myriad ways in Froman’s own life. In 2011, Rabbi Froman visited a Muslim village, speaking out against settlers who had vandalized a mosque and defamed Mohammed. In a surreal moment captured on video, he began his speech by leading a chant of Allahu Akbar – Arabic for “God is great!” – that inspired a spirited reaction by the local Muslim community. Froman would often emphasize how God’s overriding greatness is something that Judaism and Islam embrace equally. (Allahu Akhbar is cognate to El Kabbir in the Hebrew Bible (Job 36:5), which likewise means “God is great.”) Emphasizing shared religious values, and participating in religious acts representing those values, was central to creating cross-religious community. Such jointly religious groups could then facilitate building society, despite national-religious tensions. For peoples with such deep religious convictions, especially as relating to the sanctity of the land, it would be impossible to build mutual respect except through finding religious common ground, both literal and figurative. Central among these shared religious convictions, Froman identified what he called a primitive connection to the Land shared by religious Jews and Muslims, one which was impossible for “the West” to understand. Froman specifically notes his decades of dialogue with Palestinians as inspiring his emulation of his neighbors’ connection to the Land, one that his fellow Israelis in Tel Aviv could never understand.

Under God

Theologically speaking, Froman’s submission to God, also inspired by Rabbi Nahman, stands at the center of his account of peace. Political borders and the Green Line made no difference to him: any religious person living in the Holy Land had a right to live there, in peace, and use of force was justified and necessary to enforce that right. All of this builds on the idea that God’s land does not belong to any people in particular. As Froman put it: “I am a citizen of the State of God. My President is God. It’s not so… important who is the man, who is the government.” To this end, Froman advocated with equal strenuousness against Jews attacking Palestinian communities and Palestinians attacking Jewish communities. Froman at times expressed a willingness to live in a Palestinian state, as long as there were assurances that Jewish communities would be protected. This view reflected a certain degree of post-Zionism, but it was a post-Zionism stemming from a doubling down on assertion of a religious right to the Land, rather than a retraction or attenuation of that claim.

This is how Froman could talk about Jews and Palestinians “sharing a religious faith,” and how he could hope that peace would be achieved, “inshallah, if God wills it.” (As above, Froman’s use of Muslim language – which he argued often represented proper Jewish theology as well – was meant to underscore and develop common religious ground.) Within this approach, there are three parties to Froman’s account of the pursuit of peace, as Jews and Muslims join with God (or, rather, “under God”) as they engage in building a peaceful society in the Land.

Menachem Froman visiting Yasser Arafat at his Ramallah compound (c. 2001) — Source

Menachem Froman visiting Yasser Arafat at his Ramallah compound (c. 2001) — Source

Dialogue

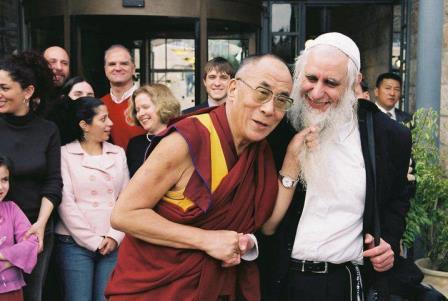

Froman believed that it was necessary to build a deep rapport between the two parties to the dispute over Israel-Palestine. He sought to do so not through goal-oriented or consensus-building negotiation, but through dialogue between the parties, finding common ground and areas of shared (religious) interest and passion as a way of overcoming fundamental disagreement. Froman participated in religious dialogue in a broader sense as well – he convened sessions among the three “Abrahamic” religions and had meetings with the Dalai Lama and other religious leaders over the years. All of this was part of the goal of building shared understanding among different religions, part of a messianic view of bringing people of all faiths together in joint understanding of God.

It is worth noting that Froman was messianic in his belief, seeing the hoped-for Israeli-Palestinian peace as the first step between healing the rift between Jews and Arabs in the Middle East, and, ultimately, to bridging the gap between Islam and the West. This aspirational model was represented by a plan for an apolitical Holy City of Jerusalem jointly controlled by Jews, Muslims, and Christians standing at the geographic and conceptual center of this unified religious world.

Empathy

Froman’s position was unusual. We are more familiar with the tendency among people who are deeply committed to the Land to exclude any other nation or religion from having rights to that Land. Those more generous in affording rights to others might be willing to do so because they are less intense in their own connection to the Land. Froman defied that usual correlation, being as fiercely committed to his fundamental religious rootedness to the Land as any extremist settler, and at the same time extending that connection to his counterparts, his Palestinian Muslim neighbors. This position essentially did not exist in Israeli politics outside of Froman and his small circle. Such an uncommon philosophy sets aside the usual rhetorical dichotomy of ally-enemy and chooses instead to find common ground with the Other, and even to identify in some way with them. As Rabbi Froman put it: “Jews and Arabs are like Siamese twins… if one suffers the other does too; if one does well, so does the other.” This identification not only with his own coreligionists but also with “the other side” paved the way for Froman’s theology of shared rights. It yielded a commitment to producing together a state under God that would sufficiently represent the narratives of the most religiously committed among both parties, the most passionate advocates of the sanctity to the Land and their religion’s rights to it. Once the most religiously committed parties were on board, the secular Israelis and Palestinians would fall into place as well. This was Rabbi Froman’s path.

Fig. 3: The Dalai Lama with Menachem Froman in Jerusalem, February 2006 — Source

Fig. 3: The Dalai Lama with Menachem Froman in Jerusalem, February 2006 — Source

Co-Producing with the Enemy?

Froman’s commitment to working with the entire Palestinian people, and especially its most radical elements, meant that he was willing to meet and discuss these plans with anyone. Over the years, he met with not just Mahmood Abbas but with Yasser Arafat and Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, who for much of their tenures were shunned by mainstream Israeli politicians and moderates, let alone settlers. Froman did not accept their actions – he describes himself telling Yassin that he will burn in hell for supporting terror – but he also realized that they saw themselves as engaged in self-defense, and that they needed to be a part of any solution. And he was willing to meet with anyone open to creating a peaceful society, and achieved remarkable interest, certainly on the Muslim side. For this openness to meet with sworn enemies of Israel, especially during the second intifada, Froman was widely criticized, including by his own followers and family.

Over the years, Froman found partners to sign several preliminary agreements. This includes both the Alexandria Declaration in 2002 by Christian, Jewish, and Muslim leaders from the Holy Land pledging steps towards peace, and the Froman-Amayreh Agreement in 2008 laying out a more comprehensive path to peace, jointly produced with Hamas-affiliated journalist Khaled Amayreh. Beyond this, however, Froman was not successful in translating these agreements into facts on the ground.

What is Next?

After his untimely death from cancer in 2013, some have continued to follow Rabbi Froman in his pursuit of peace between Jews and Muslims in the Holy Land. His wife, Hadassah, and several of their children are active in regular interfaith events aiming to build goodwill between Jewish settlers and their Muslim neighbors. The Roots-Shorashim-Judur project continues some of Froman’s work in the Gush Etzion area of the West Bank, including through representatives Khaled Abu-Awwad, Rabbi Hanan Schlesinger, and others. A theologian, Rabbi Yaakov Nagen, participates in interfaith meetings, often co-presenting with Muslim faith leaders, and is working on a theology that emphasizes points of commonality between the groups. Beyond the individuals continuing his projects, Froman set out an ideological approach to peacemaking as collaboration under God that may inspire those who did not know him personally.

Even with the various continuators of Rabbi Froman’s path, the prospects of this approach are not clear. (This author will admit to having doubts about the approach, as well.) The tenets of his ideology can be seen as a form of heresy to nearly all parties involved. It rejects the two-state solution that has long been universal and nearly sacred in the peace camp, in Israel and internationally. It rejects the political claim of exclusive Israeli (as opposed to Divine) right to the land, key to the Religious Zionist ideology that Froman himself participated in. It rejects the prospect that settlers will have to vacate their homes, unlikely to be acceptable to Palestinians who see this as a necessary step in any final agreement. Policy people will call this approach hopelessly naïve. And, on a theological level, the call for an integrated theology and community produced by Muslims and Jews, and especially their most religious adherents, can be seen as blasphemous to those with more narrowly particularistic theologies.

Still, in certain Religious Zionist circles Rabbi Froman’s creative political theology has grown in popularity since his passing. Perhaps it will have its moment on a policy level, as well, as confederation is beginning to be taken seriously as a possible political ‘endgame.’ Whatever the future may hold, this unique approach to thinking about – and with – one’s neighbors, the emphasis on inexorable interconnectedness rather than adversarial competition, and the focus on God over nation, offers much to think about in considering possible political (and apolitical) theologies of co-production.

Further readings

Harvey Stein, “A Jew Shouts ‘Allahu Akbar,’” Times of Israel, March 17, 2013, accessible at https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/a-jew-shouts-allahu-akbar/.

Nesya Shemer, “‘God’s most beautiful name is peace’: Rabbi Menachem Froman’s vision of inter-religious peace between Israelis and Palestinians,” Israel Affairs, 27:3 (2021), 493–516.

Benjamin Schvarcz and Miriam Billig, “The Froman Peace Campaign: Pluralism in Judeo-Islamic Theology and Politics,” Politics and Religion (2022), 1–20.

Menachem Froman, “Specifically a Settler Like Me” (in Hebrew), Haaretz, July 20, 2005, accessible at https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/2005-07-20/ty-article/0000017f-f2e1-d5bd-a17f-f6fbd65a0000.