Maureen Attali , 2023

The Cave of Salome: Spatial appropriation and ritual co-production in Late Antique Palestine

The beginnings of pilgrimage to the tombs of major religious figures remain somewhat mysterious. While there is archeological evidence of this practice among followers of Jesus by the late 1st century, it’s uncertain whether or not this was a continuation of an already established Jewish custom. At this point in time, funeral rites were indeed performed by Jews at their family graves, some very similar to those of their non-Jewish neighbors. However, we do not know exactly when those practices coalesced with the firmly established belief that the remains of the dead held power, thus giving rise to tomb pilgrimage.

The whole process is nevertheless documented by a few archaeological sites. Among those is the tomb of Salome, a Jewish female character embedded in the story of Jesus’s life. What insights does this site offer us about the co-production of tomb pilgrimage, which, by Late Antiquity, was practiced by Jews and Christians alike?

A Jewish burial cave turned into Christian pilgrimage site

In the 1980’s, a burial cave dug between the 1st and 2nd centuries CE was found some 30 miles southwest of Jerusalem, at a location named Ḥorvat Qaṣra. The building’s original architecture is typical of Jewish tombs from this time-period (Fig. 1). Made up of an antechamber and three inner chambers, it included seven burial niches (in Hebrew, kochim) dug perpendicular to the walls, a few oil lamps, and the remains of four stone ossuaries where bones were deposited after the body had desiccated.

From the 5th century onwards, the site was heavily remodeled. A cross was carved over one of the burial niches. An archway was added to the entrance of one of the inner rooms, now outfitted with an apse, columns, a chancel, and a chancel screen. The room had been turned into a chapel, with large stone slabs identified as an altar and benches respectively. Another apsed room had three cross carvings and niches in the wall; one was covered in soot. According to recent excavations, a 350 square meter forecourt with stone arches and a mosaic pavement was installed before the cave. There, dozens of intact lamp oils dated to the 8th and 9th centuries were found.

All indicators point to an early Roman Jewish tomb which became a Christian pilgrimage site during Late Antiquity and remained active well into the early Islamic period. Pilgrims could buy a lamp in the dedicated forecourt area, use it to light their path and leave it in the niche as an offering, as was usual in such places.

The church of Holy Salome, a companion of Jesus

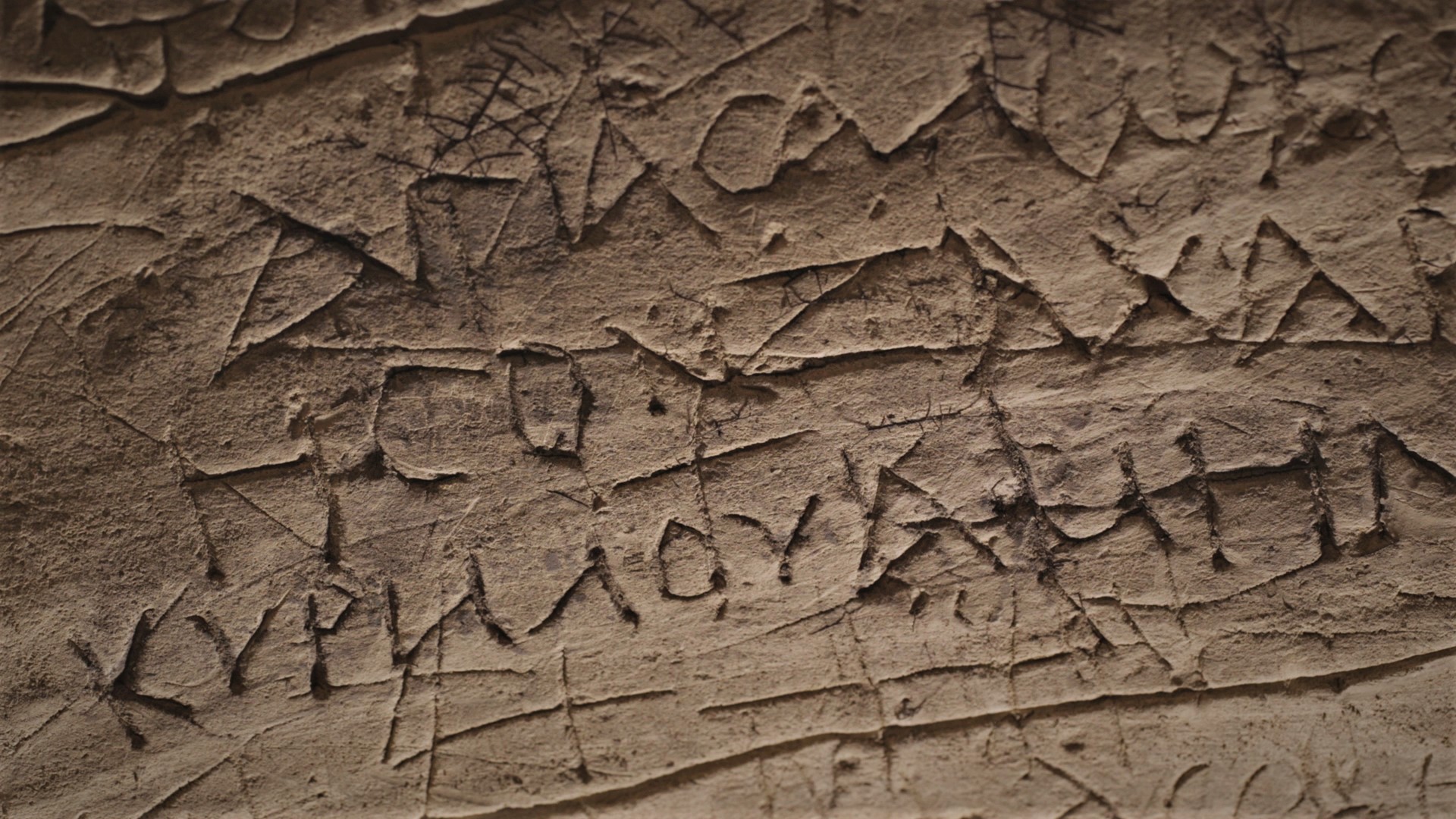

This interpretation is supported by the 55 inscriptions and graffiti etched on the walls; most are in Greek, with some in Syriac and Arabic. The formulas are typical of Late Antique pilgrimage sites, with invocations to the Lord (Kyrie) and the faithful asking to be remembered (mnêsthêti). Many include specific Christian phrasings and designs: the name “Christ”, crosses, and a design known as an ichthys wheel. It’s a circle divided in six equal parts by lines which form the letters of the Greek word ichthys, spelled ΙΧΘΥΣ. Ichthys meant “fish” but was used as an acronym for the phrase “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior”.

Several Greek inscriptions mention a “Holy Salome” and her cult. One, engraved on the arched entrance to the chapel (Fig. 2), reads:

Fig. 2: Inscription on the chapel’s entrance (© Emil Aladjem, IAA).

“O Holy Salome (Hagias Salômê),

have mercy upon Zacharias,

son of Kyrillos!

Amen.”

Next is the following dedication, preceded by a cross, by the deacon of a church dedicated to the same figure:

“Abbas Agapios, the sinner,

deacon of Holy Salome,

set [this] up.”

Another nearby inscription also references “Holy Salome” and seemingly identifies the whole place (hieron) as her own. The Arabic inscriptions are similar in content: the authors, bearing Christian names, invoke Salome and the messiah (masih).

So, who is this Salome whose purported tomb was visited and revered by Christians in the Judean hill country?

A Christian tale of many Salomes

Christian tradition knows of several women bearing this name in Jesus’s entourage. According to one Gospel account, Salome, Mary Magdalene, and Mary mother of James and of Joses were early followers of Jesus who accompanied him from Galilee to Jerusalem. They witnessed his crucifixion and, when they came to his tomb to anoint his corpse, were the first to be told about his resurrection (Mark 15:40; 16:1-8). Since a parallel passage from another Gospel (Matthew 27:56) doesn’t name Salome but instead lists Zebedee’s wife along with Mary Magdalene and Mary, some suggest that the Salome who went to Jesus’s sepulcher was Zebedee’s wife. Others distinguish between the two characters (Diatessaron 52:21-23). In some Christian writings (Gospel of Thomas 61; First Apocalypse of James 40:25-36), the Salome who followed Jesus is explicitly referred to as one of his female disciples.

Another strand of tradition has a woman named Salome implicated in the birth of Jesus. In the Protoevangelium of James, a very popular 2nd century Greek apocryphon, this Salome was the first, after the midwife, to bear witness that Jesus was brought forth from a virgin; she was also the recipient of the newborn’s first miracle (Protoevangelium 19:3-20:4). Here, Salome appears to be Jesus’s sister of the same name (Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion 78.8.1), one of the children of Joseph and his first wife. From the mention of a woman named Salome at Jesus’s birth sprung stories that Salome was actually the name of the midwife, as passed down in Latin texts (Infancy Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew 13) and Coptic texts (Discourse by Demetrius of Antioch on the birth of our Lord).

Which Salome was revered at Horvat Qasra? The disciple and witness of the resurrection, the sister, the midwife, or some combination of these (Coptic History of Joseph 8:3), following a well-documented process of concretion of significant religious figures? For indeed, Salome’s fortune as a relative of Jesus was not over yet: a 9th century Latin medieval tradition, based on yet another Gospel list of women who witnessed Jesus dying (John 19:25), claims that Zebedee’s wife was in fact Jesus’s aunt (Epitome historiae sacrae: Brevi Christi Vitae Narratione Addita). Salome’s multiple identities ended up making her a synthesis of all kinds of possible close connections with Jesus. This could be the very reason why she received an autonomous cult at her supposed gravesite, a rather unique honor for a woman of Jesus’s circle: the relics of Mary Magdelene, another composite figure, were said to be in Ephesus (Gregory of Tours, The Glory of the Martyrs 29) but connected with another holy place, the cave of the Seven Sleepers (Synaxarion of Constantinople, July 22).

Spatial appropriation and Ritual Co-production

The history of the grave of Salome is part of a wider trend of Hellenistic and early Roman Jewish tombs being transformed into Christian holy places by virtue of association with Biblical figures. We do not know why the tomb of Salome ended up in Horvat Qasra. We can only assume that a Jewish woman named Salome was known to have been buried there, as this name was extremely popular in the region during the early Roman period. For some time, family members and descendants periodically visited the site; they performed rituals there and may have brought and deposited objects there, as fellow Jews did, for instance, in Jerusalem and Jericho. Centuries later, when the name Salome had become considerably rarer, local Christians identified her with a member of Jesus’s circle. They rekindled funeral rites that, by the 3rd century, had been expanded and institutionalized by ecclesiastical authorities as part of the cult of the saints. The site gained popularity and attracted visitors from further away. It was remodeled in accordance with its perceived holiness to accommodate larger crowds of pilgrims.

Salome, a Jewish person, became an exclusively Christian saint. She was revered at the tomb of an otherwise unidentified Jewish woman who may never have had anything to do with Jesus in her lifetime. There is no indication that Jews would have visited the site during Late Antiquity: since her holiness was derived from her proximity to Jesus, she had no religious relevance for them. The cave was thus entirely appropriated by Christians. Pilgrimage accounts who record visits to sites of purported Jewish origins show that their Jewish features – here the original layout of the burial cave – were regarded as authenticity markers as well as exotic traits by Christians.

While the cave of Salome is indeed a case of supercessionist spatial appropriation, it is also an important witness to the dynamics of religious co-production. The Christian rituals practiced there were derived from funeral rites performed by all the inhabitants of the Roman empire, including the Jews. Although the original Jewish visitors were replaced by Christian ones, the on-site rituals remained. Additionally, while Jews did no go there anymore during Late Antiquity, they did visit other sites where they performed similar rituals, sometimes alongside Christians. For instance, both communities revered the Patriarchs, buried in the Macpelah in Hebron, as well as the martyred mother and her seven sons, whose martyrdom and relics were in Daphne-by-Antioch. From a historical standpoint, the cave of Salome attests to the development of the co-produced veneration of major Biblical figures at their gravesites by Jews and Christians.

Further reading

Fig. 1: Interior view of the burial cave with inscriptions (© Reuters)

Attali, M., Massa, F., “A Pagan Temple, a Martyr Shrine, and a Synagogue in Daphne: Sharing Sacred Space in Fourth Century Antioch,” in M. Burchardt and M. C. Giorda (ed.), Geographies of Encounter: The Rise and Fall of Multi-Religious Space, Malden, 2021, pp. 75–97: https://folia.unifr.ch/unifr/documents/312381

Bauckham, R., “Salome the Sister of Jesus, Salome the Disciple of Jesus, and the Secret Gospel of Mark,” Novum Testamentum 33/3, 1991, pp. 245-275: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1561359

Di Segni, L., Patrich, J., “The Greek inscriptions in the cave chapel of Ḥorvat Qaṣra,” ‘Atiqot. Hebrew Series 10, 1990, pp. 141-154 and pp. 31-35 [summary in English]: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23456946

Di Segni, L, “On the Development of Christian Cult Sites on Tombs of the Second Temple Period,” ARAM 18-19, 2007, pp. 381-401.

Hachlili, R., Jewish Funerary Customs, Practices and Rites in the Second Temple Period, Leiden, 2005.

Jacobs, A., Remains of the Jews: The Holy Land and Christian Empire in Late Antiquity, Stanford, 2004.

Kloner, A., Drori, Y., Naveh, J., “The cave chapel of Ḥorvat Qaṣra,” ‘Atiqot. Hebrew Series 10, 1990, pp. 29-30.

Nowakowski, P., Cult of Saints, E04556: http://csla.history.ox.ac.uk/record.php?recid=E04556