Anthony Ellis , 2024

The Older, the Better: Forging a Neo-Pagan Tradition in Co-Production with Christianity and Islam

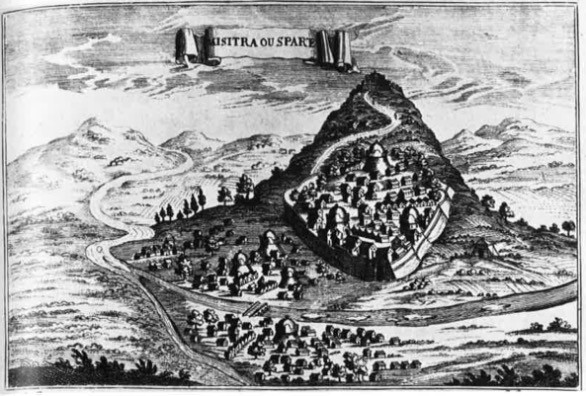

Figure 1: The city of Mistra, as depicted in 1686 by Vincenzo Coronelli.

The Laurentian library in Florence holds many medieval copies of writings of the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, most of them still dangling the long chains which once bound them to the wooden desks of Michaelangelo’s library in San Lorenzo. One manuscript, copied in 1318, looks at first glance like just another late-Byzantine copy of Herodotus’s classic work. But a century or so after its creation an eccentric philosopher, George Gemistos, better known as “Pletho”, went through the manuscript carefully editing, deleting, or rewriting selected passages. His alterations bring Herodotus into line with a new history of philosophy which Gemistos wrote as part of his clandestine revival of ancient Greek Paganism. Like so many of Gemistos’s “ancient” novelties, this looks like one side of a competitive dialogue with the monotheistic religions of his day. The Florentine manuscript illustrates how the dynamics of co-production, visible within Judaism, Christianity and Islam, could also spill over their borders into the more esoteric movements of the late medieval world.

The Pagan Philosopher and the Three Monotheisms

Gemistos “Pletho” is most often remembered for his radical break with contemporary Christianity. But his idiosyncratic scholarship is also in close dialogue with the three monotheisms of his day. Gemistos was born around 1360 into a respected Orthodox family in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople. The Byzantine Empire had long been preoccupied with the expansion of its Islamic neighbours, the Ottomans, who eventually conquered Constantinople in 1453, around the time of Gemistos’s death. But Gemistos seems to have had particularly close encounters with Christianity’s sibling religions. According to later sources, he spent part of his youth at the Ottoman court, studying with a Jewish philosopher called Elissaios. By middle age, however, he was back in Byzantine lands, in Mistra, a hilltop town in the Peloponnese (figure 1), where he lived as a teacher, judge and advisor to the empire’s ruling family. It was here that he seems to have developed his unorthodox philosophical system, laid out in a work called the Laws, which combined ancient Platonic philosophy with a polytheistic liturgy, framed as the public cult of a “Hellenic” state.

The Laws is a baffling work. The goals of its author and the role which the text played in the intellectual and spiritual life of Mistra remain a matter of speculation. But, soon after Gemistos’s death, the Laws came under unfriendly scrutiny. The text was declared anathema, most of it burned, and his rivals set about dismantling his reputation. Some claimed that Gemistos was the latest in a series of Satanic figures who had conspired against Christianity since its beginning. They inserted him into long chains of Christian heretics and apostates that led back through Mohammed or the Jews, to Plato and Greek paganism (see the previous case study on this subject). Such grand genealogies might seem very foreign to Gemistos’s way of doing intellectual history, which rejected both Scripture, revelation and the very idea that demons were evil, and instead used philosophy to reason about the nature of God. But the surviving fragments of the Laws reveal that Gemistos constructed historical genealogies in much the same way as his critics: He presented his own philosophy as a reiteration of the ancient wisdom of the great pagan sages of antiquity. And, like his Christian detractors, he identified all who disagreed with him as deviants who had abandoned true knowledge of God, led astray by a sophistic cocktail of ignorance and ambition. Gemistos and his Jewish, Christian and Islamic contemporaries were participating in the same genealogical game, one which they had all inherited from the Platonic philosophers of antiquity.

Gemistos’s Account of the History of Theology: Forging a New Past

At first sight, the intellectual genealogy Gemistos sketches in his Laws is refreshingly new. He never appeals to the authority of prophetic or scriptural revelation: no Hebrew Bible, Talmud, or Qur’an; no rabbis, Church Fathers, or Hadith; no Christ, no Apostles, no Mohammed. This alone makes his writing almost unique in the religious movements of the late-medieval Mediterranean. But once we consider the structure of his claims, deeper similarities emerge. Gemistos did not abandon the tradition of appealing to ancient authorities. He simply appealed to a different set of authorities. Following the ancient Platonic tradition, Gemistos claimed that his own philosophy was that of the legendary pagan sages and philosophers of antiquity, from Zoroaster and Lycurgus to the Brahmans of India and the Magi of Media, and from the “Seven Sages” of Greece to Pythagoras and Plato. Gemistos might have been using a different cast, but he was staging the same play. His tradition also had its apostates: “poets” and “sophists” who, in their thirst for glory, used “innovations”, false logic and fake miracles to deceive the uneducated and indoctrinate the young. Gemistos, in effect, outlines a Neopagan heresiology which dismisses Jews, Christians, and Muslims as apostates from the ancient wisdom. In this, his sketch of the history of philosophy sits much closer to medieval Christian thought than to histories of philosophy like that penned by Diogenes Laertius.

Gemistos’s enthusiasm for appropriating ancient authorities exposed him to the same problems that had long plagued Christians, Jews and Muslims: What to do when one’s authoritative texts say the wrong thing? Since antiquity, a popular solution was allegorical exegesis, which allows the interpreter to read the text against the grain to identify an acceptable “hidden message”. But Gemistos rejected this form of esotericism, perhaps objecting to its arbitrariness, perhaps disliking its association with Christianity. Instead, he took a more radical path, one which had also been quietly taken by many a Christian intellectual: Forgery. Gemistos physically rewrote his copies of ancient texts when they contradicted his own views. His personal manuscripts of ancient Greek literature teem with passages in which Gemistos has rewritten the history of religion in his own image.

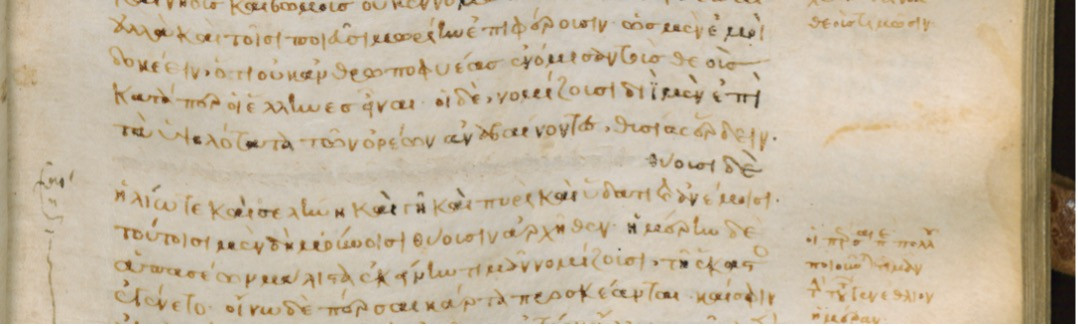

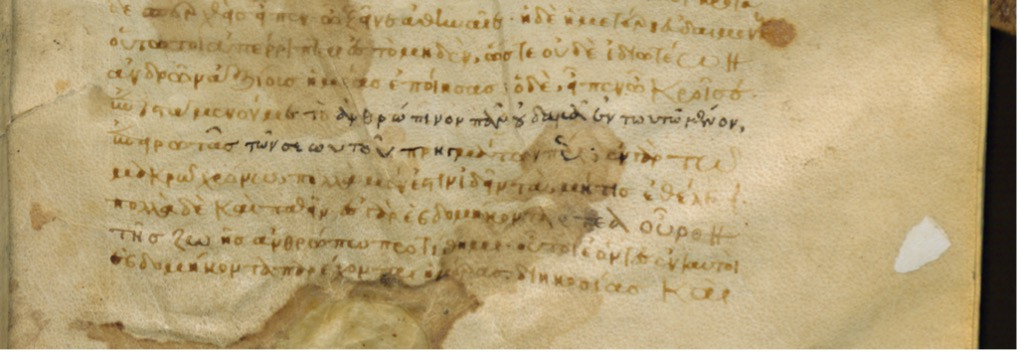

Figures 2 and 3 offer snapshots of his working methods. The former shows a passage in the middle of Herodotus’s description of the theology of the ancient Persians, important for Gemistos who considered them the disciples of Zoroaster. Today most of a line of text is missing, deleted by Gemistos because it contradicts his own theology. Figure 3 shows a more subtle technique. In a speech given by the ancient Greek sage Solon, Gemistos has erased part of two lines, which he considered blasphemous, and inserted his own replacement, written in a careful imitation of the author’s style and dialect. The new text, in darker ink, brings Solon’s words closer to Gemistos’s own neo-Platonic orthodoxy and removes the pessimistic idea that God disrupts human life out of a malevolent “jealousy” felt towards humanity.

Figure 2: Pletho modifies the theology of the ancient Persians as told by Herodotus Histories 1.131.2 (Florence, BML, Plut. gr. 70.6, fol. 33r)

Figure 3: Pletho rewrites the theology of Solon of Athens as told by Herodotus Histories 1.32.1 (Florence, BML, Plut. gr. 70.6, fol. 8r)

The problem of forgery clearly interested Gemistos. In 1439, at the Council of Florence, Gemistos claimed that the Latin version of the Nicene Creed was a recent forgery to which the contentious filioque-clause had been dishonestly added by Catholics. By this date, Gemistos had long been secretly tampering with his own ancient Greek manuscripts. It seems likely that he saw himself as part of a complex competition of forgery and counter-forgery, practiced by people intent on discovering themselves in the past – just as he was.

Conclusion: Co-Production beyond the Abrahamic Religions

These changes reveal how much Gemistos shared with the religious cultures of his day. Like the Catholic and Orthodox Christians who attacked him, Gemistos was deeply preoccupied with creating family trees for both himself and his enemies – and he was willing to manipulate the evidence where necessary. The competing intellectual genealogies produced by Gemistos and his contemporaries reveal how the same discursive strategy, co-produced in antiquity by pagans, Jews and Christians, continued to flow across the identitarian boundaries of the Middle Ages.

Further Reading

Cohen, S. J. D. 1980. ‘A Virgin Defiled: Some Rabbinic and Christian Views on the Origin of Heresy’, Union Seminary Quarterly Review 36: 1–11.

Ehrman, B. D. 2011. The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. New York (revised edition).

Ellis, B. A. 2024 ‘Neo-Pagan Censorship and Editing in Medieval Sparta, Or: How Gemistos Pletho Rewrote his Herodotus,’ Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Papers 78: 315–54.

Mariev, S. 2019. ‘Scholarios’ Account of Plethon's Jewish Teacher Elissaios as a Historical Fact and Literary Fiction’, in M. Grünbart (ed.) Verflechtungen zwischen Byzanz und dem Orient. Berlin: 53–69.

Monfasani, J. 1992. ‘Platonic Paganism in the 15th Century’, in M. O. Di Cesare (ed.), Reconsidering the Renaissance: Papers from the Twenty-First Annual Conference. Birmingham, NY, 45–61

Pagani, F. 2009. ‘Damnata verba: Censure di Pletone in alcuni codici platonici’, Byzantinische Zeitschrift 102.1: 167–202.

Pilhofer, P. 1990. Presbyteron Kreitton: Der Altersbeweis der jüdischen und christlichen Apologeten und seine Vorgeschichte. Tübingen.