Paul Neuenkirchen, 2024

A Material Case of Co-Production: An Arabic Christian Torah and the Qurʾān

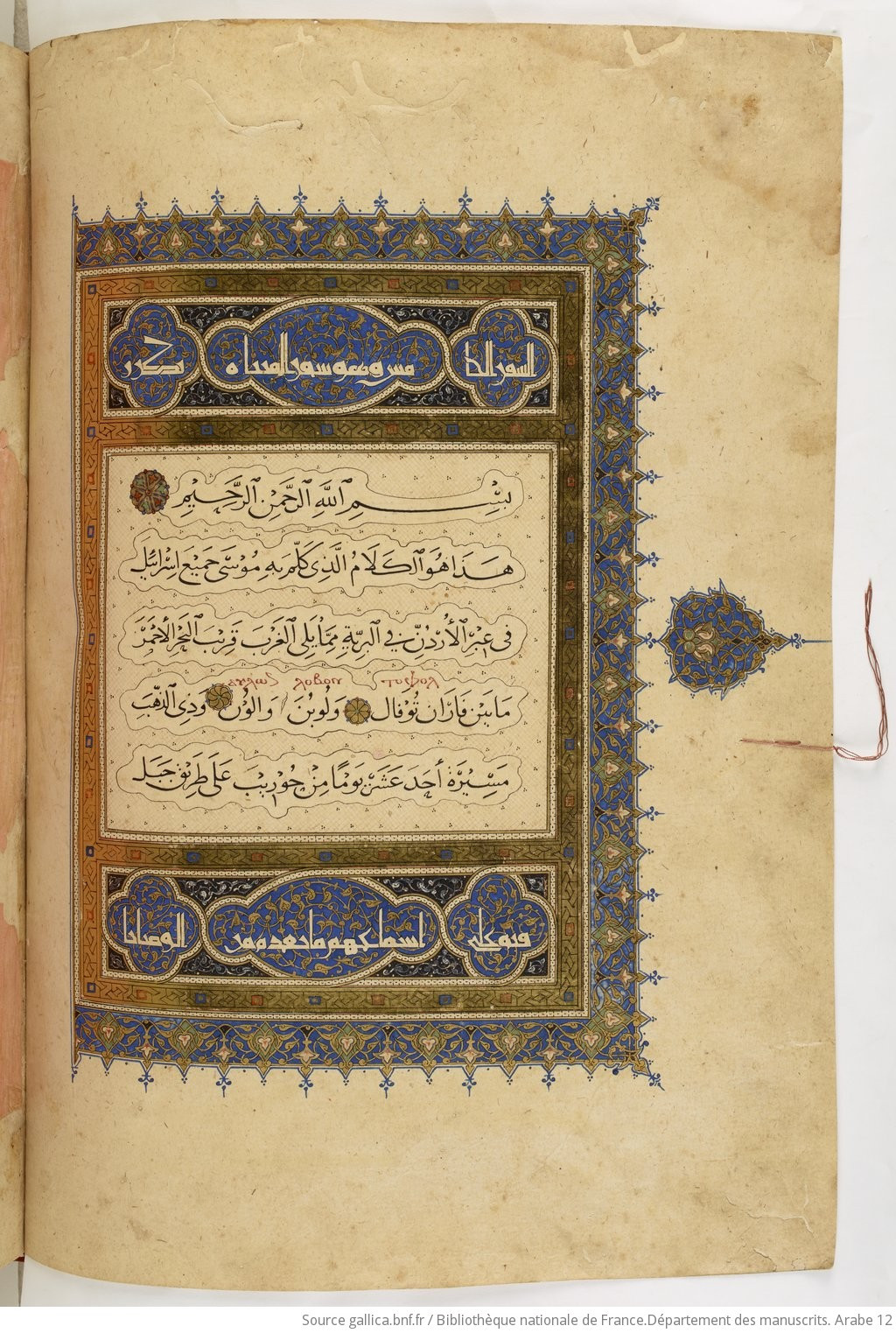

Opening page of the Book of Exodus (Ex 1:1-5) in Arabic, copied in 1353 CE, possibly in Egypt (Bibliothèque nationale de Frace Arabe 12, fol. 72v)

At first glance, the Bibliothèque nationale de France Arabe 12 manuscript looks like a typical Qurʾān from the Mamluk period, painted in blue and gold tones, decorated with geometric and floral motifs framing an Arabic vocalized text written in the Mamluki nasẖ script and including a basmala preceding the first verse. Except that it is not a Qurʾān.

Upon closer inspection, we learn from the large white Arabic Kufic letters contained in the intricately decorated sarloh-s (frontispieces) located at the top and bottom of the page that this folio is the opening of the “second Book,” which is none other than the “Book of Exodus” (sifr al-ẖurūj), the second of the Bible. Indeed, BnF Arabe 12 is a complete Torah or Pentateuch, as explicitly mentioned in a concluding prayer found on the penultimate folio, which states: “The holy Torah is completed with peace from the Lord. Glory and honor to God for eternity. Amen.” If this Arabic manuscript is not a Qurʾān but a Torah (i.e., a collection of the five first books of the Bible), one might wonder whether it is a Jewish or a Christian artifact. One might also ask why a copy of the Pentateuch resembles a Qurʾān in everything but its content. We can begin to answer these questions by looking at the colophon featured on the last folio, which reveals a proper name and a date.

The name on the colophon is that of Jurjus, son of the priest Abū l-Mufaḍḍal b. Amīn al-Mulk Luṭf Allāh, and it is preceded by the Arabic expression ʿalā yad (“by means of”), which seems to indicate that he is not the copyist but the person who commissioned the manuscript (the usual expression used by copyists is kataba or “written by”). Recent studies have identified him as the head of the Church of the Virgin in Damascus, a position he held until he left for Egypt, where he was elected Patriarch of the “Jacobite” Church in 1362–1363 CE. This, as well as the fact that proper names are written in Coptic above the Arabic throughout the manuscript (see fig. 1 above), seems to point to a Christian origin.

The date of completion is given according to both the Coptic and Hijra calendars, corresponding to July 23, 1353, in the Gregorian calendar. Although the manuscript does not mention where it was produced, its resemblance to other contemporary works suggests that it was copied either in Damascus or in Egypt. The latter is more likely given the presence of Coptic words, and because the fully vocalized Arabic proper name of the manuscript’s patron reveals dialectal forms specific to Egypt (Jurjus and qiss are Egyptian dialectal forms of Jirjis and qass, respectively).

By the time the Arabic Pentateuch was copied, the Mamluks (1250–1517 CE) had been in power in Egypt for just over a century. The few years during which the Mamluk sultan al-Ṣāliḥ Ṣalāḥ al-dīn Ṣāliḥ (r. 1351–1354 CE) reigned over Egypt was a particularly trying time for the Coptic community in Egypt, as the sultan ordered his governors to remove Copts from their administrative positions and had the Coptic Patriarch Mark IV (1349–1363 CE) imprisoned and tortured. Many monasteries and churches were also destroyed, and cases of monks being burned alive are recorded throughout the 14th century. This difficult historical context has been put forward by Mathilde Cruvelier to explain why Christians would have adopted the visual codes of Qurʾānic manuscripts, allowing them to “blend in” with the Muslim landscape. She concludes by writing that “adopting the motifs used in Muslim book art for the ornamentation of their own religious works meant erasing all cultural barriers and inter-community boundaries at a stroke, and in fact mitigating differences that could prove dangerous for this part of the Coptic community” (Cruvelier 2010, 228 – my translation).

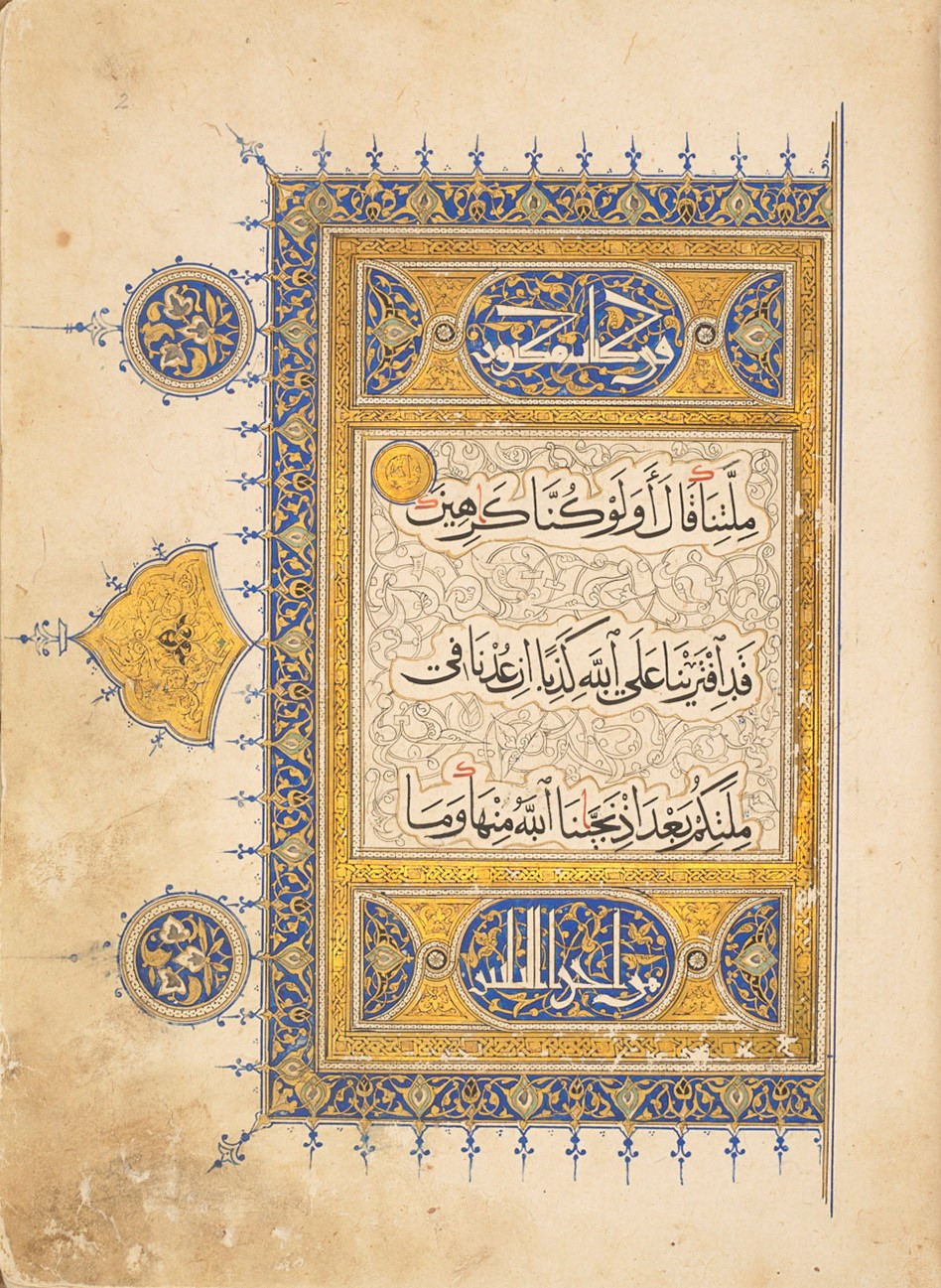

These motifs, such as the geometric and floral decorations or the fully vocalized Arabic script, undoubtedly link this Christian Torah manuscript to contemporary Islamic manuscripts and, more specifically, to contemporary Qurʾāns. One such example was produced some fifty years later: fig. 2, below, is a folio from the British Library ms OR 848, featuring the opening page of the ninth volume of a Qurʾān (sūrat al-Aʿrāf, Q 7:88–89) commissioned by the Mamluk sultan Faraj b. Barqūq (r. 1399–1405 CE).

Opening page of the ninth volume of a Qurʾān (Q 7:88-89) commissioned by the Mamluk Sultan Faraj ibn Barqūq (r. 1399-1405 CE) in Egypt (British Library ms OR 848, fol. 2r)

Comparing some of the common features of the two manuscripts unveils an impressive moment of the co-production of sacred manuscripts between Islam and Christianity.

The color palette, composed mainly of gold and blue, used on the opening page of the Book of Exodus as well as in the rest of the manuscript, echoes a common chromatic expression found in contemporary Qurʾāns, as can be seen in BL ms OR 848 but which is conspicuously absent in other Christian Coptic manuscripts, where one tends to find the chromatic palette of red, yellow, and green. In the same vein, unlike most Coptic sacred manuscripts that feature representations of animals or humans (especially saints), BnF Arabe 12 lacks any figurative representations and instead uses only geometric and floral motifs. This aesthetic can be said to represent not only contemporary Qurʾānic manuscripts, but the entire Qurʾānic manuscript tradition. Moreover, while the introductory pages of Coptic manuscripts usually feature crosses, this Arabic Pentateuch does not have a single one, making it difficult to identify it ab initio as a Christian manuscript.

The text of BnF Arabe 12 is written in the Mamluki nasẖ script used in contemporary Qurʾāns. And, remarkably, unlike most other Christian Arabic manuscripts from Egypt, it is fully vocalized, just as all Qurʾāns from this time period are. The Arabic verses of Exodus are also inserted in a text box that resembles a cloud, a common feature of contemporary Qurʾāns, as can be seen in BL ms OR 848.

Finally, it is remarkable that the first four Books of this Pentateuch begin with a different version of what can only be called a “modified basmala,” which retains the same phrase “In the name of God” (bi-smi Llāh) as in the Qurʾānic convention, but then modifies the unmistakably Islamic al-Raḥmān al-Raḥīm portion with various qualifiers of God. Thus, before the first verse of Exodus, we find the following expression: “In the name of God, the Pre-Existing, the Unique, the Eternal” (bi-smi Llāh al-qadīm al-wāḥid al-azalī). Interestingly, these qualifiers are also frequently used to describe God in various Muslim theological treatises, allowing this basmala to be recognized and embraced by a reader belonging to any of the “Abrahamic” faiths. But even more striking is the fact that this manuscript’s fifth Book, the Book of Deuteronomy, is introduced on folio 237v by an actual full Qurʾānic basmala, reading, “In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate” (bi-smi Llāh al-Raḥmān al-Raḥīm).

Opening page of the Book of Deuteronomy in Arabic, copied in 1353 CE, possibly in Egypt (Bibliothèque nationale de Frace Arabe 12, fol. 237v)

These features, shared between the Qurʾānic manuscript tradition and a specific Christian Arabic Pentateuch, give us a rare glimpse into a case of material co-production that goes beyond a simple appropriation of Islamic book culture designs by Christians. Rather, it demonstrates a deep knowledge, reworking, and use of typical Muslim motifs – whether visual or textual – as can be seen in the case of the basmala. The introduction of a Scripture sacred to Christians, but also to Jews, with a Qurʾānic basmala is indeed a unique example of religious co-production, possibly a Christian attempt to blend in a dominantly Islamic context, or the result of the sustained, daily interactions of Muslims and Christians in 14th century Egypt. And indeed, the numerous affinities between BnF Arabe 12 and contemporary Qurʾāns illustrate either the transmission of this expertise from Muslim scribes to Christian ones or, more probably, that the Pentateuch manuscript was produced by Muslim artisans for a Christian patron.

Further reading

Boud’hors, Anne (ed..), Pages chrétiennes d’Égypte: Les manuscrits des coptes (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2004).

Cruvelier, Mathilde, “Le Pentateuque de la Bibliothèque nationale de France: un manuscrit copte-arabe du 8e/ XIVe siècle,” Annales islamologiques 44 (2010), 207–235.