Shlomo Zuckier, 2024

Debating Hypocrisy: A Rabbinic Response to the New Testament’s Dissembler Diatribe

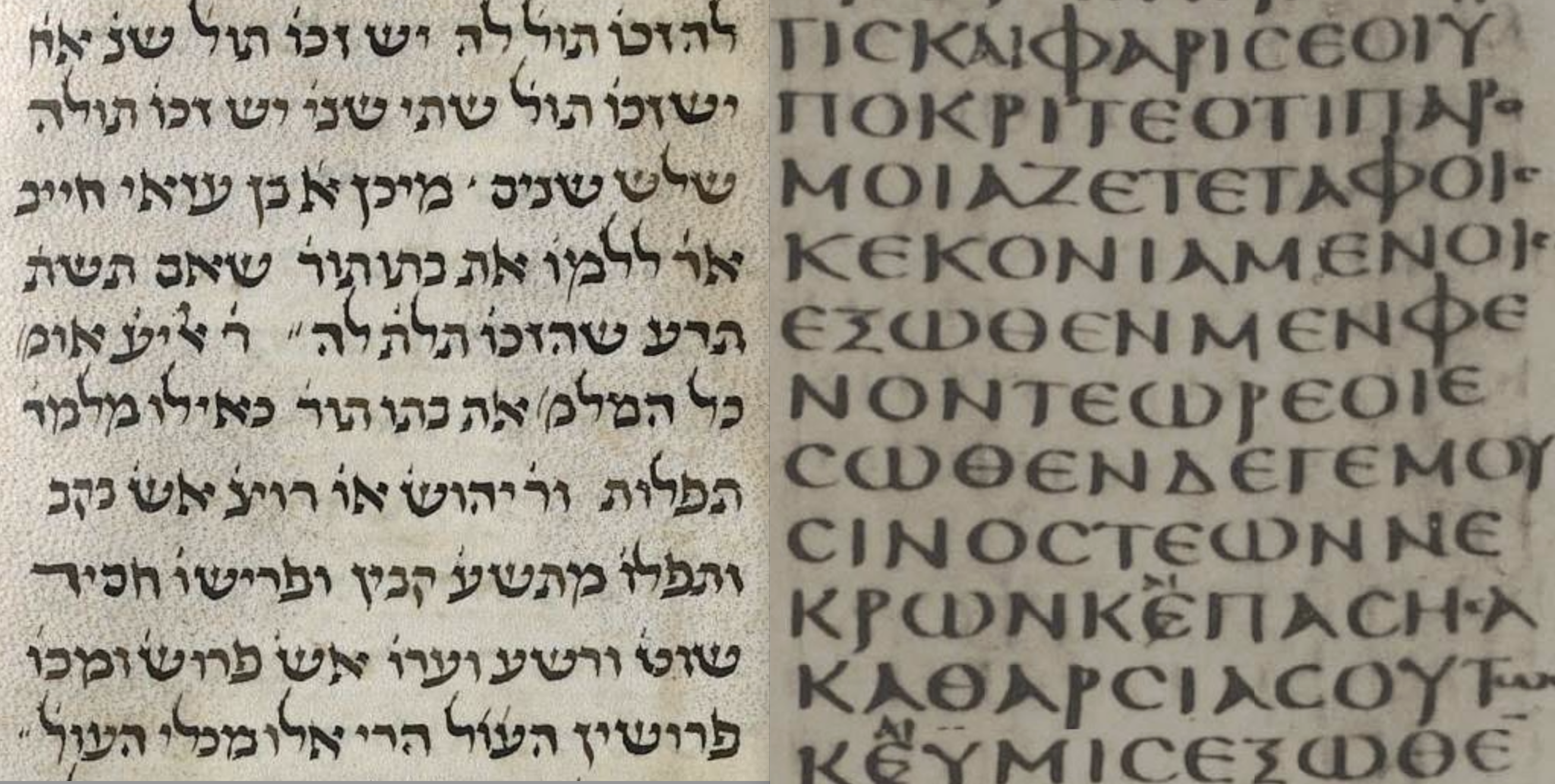

Left: Munich MS 95 (1342 CE), p. 504 (discussion of pharisees from tractate Sotah 22b); Right: British Library MS Add. 43725 (= Codex Sinaiticus; 4th cent.), unnumbered folio (Jesus' words from Matthew 23:27a)

Early Christian texts develop a terminology of hypocrisy that represents their rivals as dishonest dissemblers, drawing upon earlier concepts and terms in Second Temple Judaism and Greco-Roman culture in producing this caricature. This discourse applies the Greek term “hypokritai,” originally meaning “actor” or stage player,” in its critique of alleged performative piety on the part of the Pharisees, Jesus’ rivals. The trope criticizing Pharisees as hypocrites appears multiple times in the New Testament, especially in the Synoptic Gospels, and continues throughout later Christian theology, usually directed against rabbinic Jews, but deployed equally against other religious foes associated with Pharisaic practice. This essay examines one short passage in the Babylonian Talmud that seems to parry that accusation against Pharisees, partially accepting and partially denying the critique, in service of inoculating the rabbis from the claim of hypocrisy and resulting in a coproduced Jewish-Christian account of hypocrisy.

This passage from Matthew 23 represents the instances where New Testament texts identify Jesus’ opponents in these terms:

27 “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites (hypokritai)! For you are like whitewashed tombs, which on the outside look beautiful but inside are full of the bones of the dead and of all kinds of uncleanness. 28 So you also on the outside look righteous to others, but inside you are full of hypocrisy and lawlessness…

The charge of hypocrisy is made intelligible by representing the discrepancy between outer appearance and inner essence in terms of white-washing or painting, a metaphor here deployed to attack Jesus’ sectarian rivals, the Pharisees.

While the rabbis do not often betray a direct knowledge of Christian sources, and do not utilize the Greek word hypokritai, the following Talmudic passage seems to represent a rabbinic response to this New Testament trope. As we will see, it describes certain impious dissemblers as tzevu’in, literally “colored,” one of the terms that roughly stands in for the term “hypocrite.” Short but direct, this passage (Sotah 22b) appears both to be aware of the Christian critique and to parry it:

King Yannai (Jannaeus) said to his wife [Queen Alexandra]: Do not fear the Pharisees nor those who are not Pharisees, but rather [fear] the tzevu’in who appear similar to Pharisees, whose actions are like the actions of [the sinner] Zimri yet they seek reward like [his zealous killer] Phineas.

Although detached from Pharisees, the concept of hypocrisy portrayed here, as attached to the tzevu’in, is strikingly similar to what we see in the New Testament Gospels. It points to someone who in truth is a sinner, but who represents themselves as a saint, and moreover seeks reward for their purported good deeds. The inconsistency between integral behavior and public comportment, the literal painting over of a sullied soul, as well as the focus on public recognition and honor, fit the Gospel writers’ description of the Pharisaic hypocrites.

The New Testament discourse on hypocrisy is paralleled here in several ways. Most clear is the specter of the association between Pharisees and hypocrisy. Notably, this prospect is not raised about contemporary rabbinic Jews (as Christians at the time might have applied it), but is rather placed in the mouth of Alexander Jannaeus, who ruled over Judea during the early 1st century BCE, when the term ‘Pharisee’ may have been in regular use. (The rabbis themselves rarely if ever refer to themselves as Pharisees, and the precise relationship between Pharisees and rabbis – both generally and in this passage in particular – is a longstanding and complicated scholarly question.)

The rabbis detach themselves from these hypocrites in another way, beyond the chronological. Their account inverts the New Testament’s association between Pharisees and hypocrites: for the rabbis, one should not fear the Pharisees nor the non-Pharisees (likely the Sadducees), but rather a different group, the true hypocrites.

Note how these hypocrites are said to “appear similar to Pharisees,” presumably because they present themselves as Pharisees despite not deserving that appellation. This teaching in some ways validates the Synoptic Gospels’ critique, arguing that there are those who present themselves as righteous Pharisees but in truth are sinners. At the same time, however, this teaching asserts that those performative Jews are no true Pharisees, but are actually tzevu’in, hypocrites dressing themselves up as righteous and hijacking the Pharisees’ deserved good reputation.

Thus, the New Testament critique of hypocrisy among ancient Jews is largely accepted; the rabbis only modify that it is relevant not to true Pharisees, but only to those pretending to be Pharisees. (Someone disagreeing with this characterization might call it the “no true Pharisee” fallacy.)

This subtle yet effective mode of parrying the New Testament’s Pharisee-hypocrite association is but one mode of rabbinic response to these polemics, alongside others that invert the critique and, using biblical characters coded as Christian, label Christians as hypocrites. This terse Talmudic tale paints a co-produced picture of religious hypocrisy that draws upon Christian anti-Jewish tropes even as it aims to exempt the rabbis from that critique.

Further Reading

Richard Kalmin, “Pharisees in Rabbinic Literature of Late Antiquity,” Sidra: A Journal for the Study of Rabbinic Literature 24/25 (2010), pp. VII-XXVIII.

Kaufmann Kohler, “Hypocrisy,” Jewish Encyclopedia, ed. Isidore Singer, et al. (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1901-1906), v. 6, p. 514.

Etka Liebowitz, “Hypocrites or pious scholars? The image of the Pharisees in Second Temple period texts and Rabbinic literature,” Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies (1759-1953) 11, no. 1 (2015): 53-67.

David Nirenberg, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (New York, 2013), pp. 48-86.

Vered Noam, “Alexander Janneus’s Instructions to his Wife,” in Shifting Images of the Hasmoneans (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 137-56.

Shlomo Zuckier, “Coproducing Hypocrisy in Jewish-Christian Antiquity: Esau, the Pharisees, and Other Hypocrites,” forthcoming.