Shlomo Zuckier, 2023

Reconstructing “God-Willing” Across Judaism, Islam, and Christianity in John Gregory’s "Notes and Observations (1646)"

The expression “God-willing” may seem ubiquitous in Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, but in fact it has a history, and that history can teach us a great deal about the co-production of piety among these three religions. The phrase was first enjoined upon believers in a passage from the New Testament, James 4:13-15, in which James prescribes that any future plans be predicated on God’s willingness. It was adopted by Islam and then by Judaism, with each community of faith providing its own prooftexts and history for the practice of uttering the phrase. The intertwining of these histories is evident in a fascinating text produced in 1646 by English bishop and orientalist scholar John Gregory.

The text, a commentary on the New Testament entitled Notes and Observations upon some passages of Scripture, enlists historical research in the work of religious exhortation, invoking Jewish and Muslim practice and tradition as it spurs Christians to heed this passage in James.

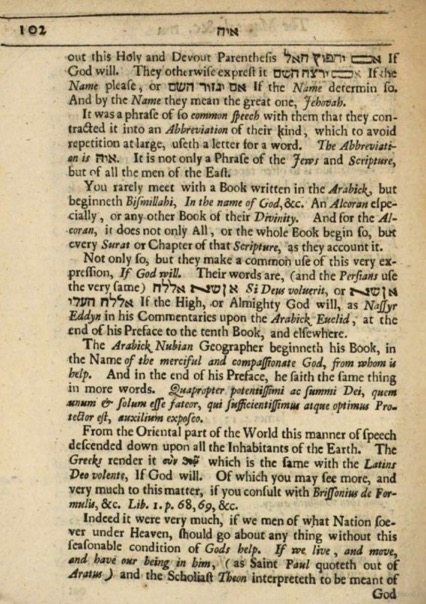

Gregory (possibly drawing from Johannes Drusius, an earlier British Orientalist) notes the “custome among the Jewes, especially and first to begin all things with God,” specifying three expressions Jews use – “if God will” (אם יחפוץ האל), “if the Name please” (אם ירצה השם) and “If the Name determine so” (אם יגזור השם), and even pointing out the frequent acrostic, איה, which stands for all three expressions, and serves as the title of his chapter (as seen on the headers of the relevant pages).

Gregory then turns to Islam (among “the men of the East”), noting the Bismillahi, the standard practice of invoking God’s name prior to Muslim study. He notes that both Arabs and Persians use the term אן שא אללה, which he spells in Hebrew letters and translates as Si Deus voluerit (if God wills).

Having established the ubiquity of the expression, the bishop moves to a diachronic mode, seeking to reconstruct its history. He asserts that “From the Orientall part of the World this manner of speech descended downe upon all the Inhabitants of the Earth,” seeing it in the Greek σὺν θεῷ and the Latin Deo volente.

This ubiquity and this history yield a normative conclusion: all believers should adopt a similar practice:

“Indeed it were very much, if we men of what Nation soever under Heaven, should go about anything without this seasonable condition of Gods helpe… certainly we ought not to venture upon anything without A Jove principium. As he ought to be in all of our thoughts, so especially in those of enterprise and designe.”

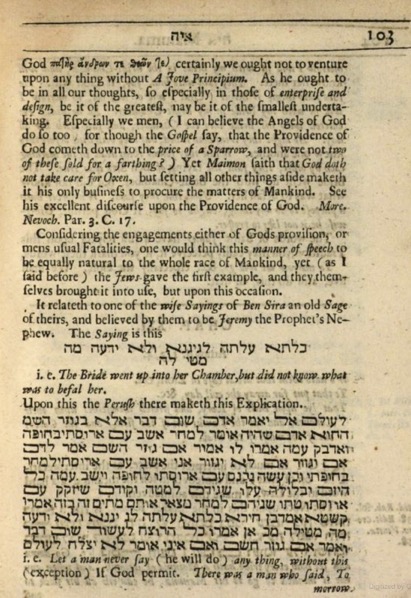

Gregory paraphrases Acts 17:28 and Paul’s teaching there that God plays a role in every human action. He then notes a debate between the Gospell’s view that God’s providence affects even a sparrow (channeling Matthew 10:29) and the Maimonidean view (Guide 3:17) that animals are excluded from divine providence. Despite that debate, all are agreed that God “procure[s] the matters of Mankinde” and should be acknowledged accordingly.

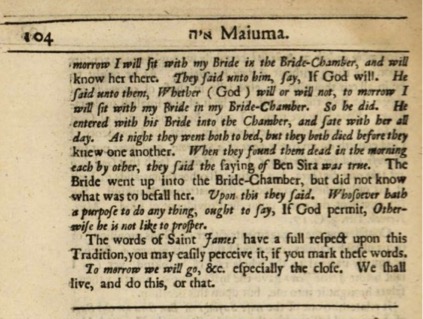

Given the strong Christian tendency to understand its norms as authorized by Hebrew scriptures, it is not surprising that Gregory puts his historical scholarship to the work of establishing a prophetic origin to this teaching. “The Jewes gave the first example, and they themselves brought it into use.” He cites the Aramaic Alphabet of Ben Sira, a medieval Jewish text composed in a Muslim context, but presenting itself as having been authored by Ben Sira--“beleeved by them to be Jeremie the Prophets Nephew”—in biblical times. The Alphabet tells the story of a groom who refused to say “God-willing” about his plans to be with his bride that evening, resulting in the death of both bride and groom. The bishop concludes: “Whosoever hath a purpose to doe any thing ought to say If God permit, Otherwise he is not like to prosper.”

Gregory’s historical reconstruction is flawed. Ben Sira is not the source for the passage in James but rather its descendant, born through the mediation of Muslim texts. And σὺν θεῷ was common in Greek literature (e.g., Sophocles and Plutarch) before any biblical influence.

But his effort presents a fascinating model for a concurrent process of scholarship and constructive theology. Gregory asserts the Jewish sources of James’ teaching and the exemplary zeal of Muslim and Jewish practitioners in its implementation. He does not do so in order to discredit Muslims and Jews or to argue the superiority of Christianity. Rather he offers his history as an inspiration for all believers to better appreciate the role of God in the world. His message is explicitly framed as relevant for all nations under Heaven: an example of a historical study of sectarian co-production put to the work of a cross-religious message.

Further reading:

Matar, Nabil. "Islam in the defence of the Anglican Church: John Gregory (1607–1646)." Journal of Islamic Studies 34, no. 1 (2023): 76-97.

A. Hamilton, ‘Gregory, John (1607–1646)’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004), accessible at https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-11467

Jillian Stinchcomb, “Ben Sira as a Baby: The Alphabet of Ben Sira and Authorial Personae,”Ancient Jew Review , January 16, 2018, accessible at